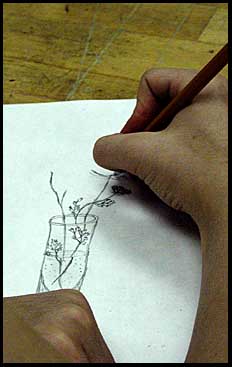

BEGINNING RITUALSI propose we start every class every day with a warm up ritual. We do a few minutes of quiet concentrated blind contour drawing from observation of a real thing, person, setup, or scene. Secondly, I suggest we end every period, after cleaning up, with another ritual. We have a discussion centered on the meanings and implications of what we did today. Between the beginning and ending rituals, during the main part of the period, we teach our projects as we always do. I remember music teachers who always had us doing vocal exercises to warm up the vocal cords and tune our ears at the beginning of every rehearsal session. The ritual centered us. Our attention was on singing. There was never a question, "Let's see, what are we doing today?" We didn't feel we were performing a concert, we felt we were practicing. Can we ritualize the art experience? The art class needs a devotional time to cleanse souls and center consciousness. Life outside the class and inside the student is turbulent, disorientating, sometimes violent, often depressing, and always confusing. How can we better help today's youth, than to give them a ritual liturgy to focus on learning art? Repeat the practice every day. Life is tense enough. Instead of striving for a unique surprise each day in art, I propose for each day to begin predictable, stable, fulfilling, skill building, brain building, and above all centering. Teach them about the joy of practice. Practice makes anything easier. Practice builds self-esteem. Practice builds confidence. AIR DRAWING: Encourage them to do imaginary drawing in the air before drawing on paper. Teach them to point with a pencil, finger, or even the nose to the subject and do a careful imaginary drawing6 in the air. Air practice is simply pointing to edge of the object and drawing slowly in the air. Draw invisibly on paper with only a finger before using a pencil. Looking carefully means following the contour slowly--about as fast as an ant could crawl along the edge. End Note6 Teach them to look carefully at the edge of the object being drawn while the pencil moves. Use a 4B or 6B soft pencil so it shows. No erasers. This is practice. Just add another line. Never look at the paper while the pencil moves, but look at the paper any other time. I never draw for them. Maybe allow erasers after it is finished, but practice with extra lines until a discovery is made. Placing

the pencil through a hole in the center of a 8 x 8 inch card hides the

drawing

and discourages sneaking a peek. Explain it to them by going to the object

being

drawn. Slowly move your finger along the edge of the object

illustrating

the deliberate careful way of drawing it. If you do this, there is no

need

to draw in front of the class or on their papers.

Encourage air practice and invisible drawing on the paper with just a finger to build confidence. Every day, have them work three to five minutes doing slow focused careful observation. Date the drawings. Place them in each student's special folder or use a sketchbook where this developmental record is kept. Every day it's the same. Nobody asks, "What are we doing today?" until this "devotional" is over. When first doing air drawing and blind contour drawing, children may be confused and annoyed by double vision. Many are able to close one eye to to avoid seeing double. If a child has problems holding one eye closed, I offer an eye patch or a piece of masking tape to alleviate the problem. If they tape the paper to hold it, they can use one hand to cover an eye while doing observation. From time to time, add new techniques to the liturgy. Try a new way to hold the pencil. Try charcoal. Try markers. Try crayons without paper on them. Try the other hand. Try it much bigger. Try it much smaller. Try white chalk on black paper. Try only negative shapes. Maybe every fifth day, explore a new way to make drawings. But always come back to basic pencil on paper. It is skill and creativity--not exotic materials or cute looking tricks that build skill and self-confidence. Why contour drawing? Why not draw the dream from last night, or two point perspective, or some other worthy learning task? While drawing from observation is not the only worthwhile learning task in art, it is fundamental for several reasons. Everybody wishes they could draw better. Observation drawing develops the parts of the brain that help us see better. Drawing ability builds self-confidence. Finally, drawing is one thing we as art teachers know how to teach. It gets students weaned from dependence on copying, which I still see in many of our schools. Observation drawing on its own is not art. However, it is one of skills that is frequently used by artists when they create art. When first and

second

graders learn observation skills, they are less apt to have a crisis of

confidence in the third grade when they begin to recognize the

crudeness

of their own work. Unfortunately, many children and adults have never been taught this simple secret of learning to draw. Many still think that drawing is an inborn talent rather than a skill that has been learned by practice. This blind observation drawing can form new brain neurons at any age, but learning this method at an early age helps form productive practice habits that build real ability. Younger brains often learn faster. Younger brains are forming learning habits that last a life-time.

Once they understand the process of observation, they have learned how to learn how to draw. They'll never need a "how to draw" book or guide. Once you can draw from observation, you need no tricks, no guide books, no formulas for faces or body parts, and no more triangle cows or oval horses. No more stereotypes. Because a difficult observation drawing can be intense concentration and hard work, three to five minutes may be long enough at one sitting. Be careful about pushing them too long, but it is also good to see what they can do. As skills develop, attention span will expand. A long session can yield very gratifying results. Repetition and routine are so important to good practice and mastery. Shinichi Suzuki, the Japanese violin teacher, talks of creative repetition. He says, "Mastery equals understanding -- plus 10,000 times!"2 As a potter, I tell my students not to expect their fingers to have brains like mine until they have made 10,000 cylinders. I have virtuosity in my fingertips, not because of some great talent, but because of much hard/easy practice. Dr. Alvaro Pascual-Leone, a scientist at the National Institute of Health, studying the brain, found that we acquire new skills in surprising ways. Using five finger piano exercises, he found that the brain's motor maps of the hand more than tripled for those who did goal oriented practice on the piano. Those who spent the same time just hitting keys showed little or no brain effects. The most surprising effect came from a third group who simply practiced by imagination. "They . . . were only allowed to rehearse mentally -- not manually -- while looking at the key board. `After five days the brains of these people were identical to those who had manually practiced . . . The same cell networks involved in executing a task are also involved in imagining it.' "3 In more recent research by Daniel Glazer related to mirror neurons, reported by Peter Tyson, it is found that subjects who have achieved physical expertise experience real learning by observation alone. While the studies are not directly using drawing students, it follows that those with the ability to draw may find that careful observation while they imagine drawing (or air drawing) will enhance their learning and physical ability to draw.

Does this mean we can devise ways to teach drawing without actually drawing? Maybe. When we really look at something while imagining how to draw it, we are already learning to draw. This may be a good way to help children prepare to draw. They can do this imaginary drawing at times it would be socially unacceptable to be drawing, as at a concert, or while listening to a boring lecture in another class. Because of their richly developed imaginations, creative people are seldom bored for long.

ENDING RITUALSHaving proposed a beginning ritual for the art period, allow me to propose an ending ritual as well. We clean up three to five minutes early. Use the remaining time to clarify and endorse today's work. This serves as a benediction time -- a closure time. The teacher poses questions. "What did we learn today?" "What did we practice today?" "Why did we do what we did today?" "How will we be better people because of what we did today?" "What will we notice more after today's class?" "What did we learn to see today?" "What did we enjoy most today?" "What did we learn to help us on our next art project?" These are some general questions. Each day's work will also have specific topics for discussion such as, "What are the best colors to use when you want things to move forward (or backward)?" Good closure matters. Review time is often the most effective learning time.

Naturally, if we don't show

examples before they work, we need to

articulate our assignments better. Not only do we speak more clearly,

we offer more preliminary learning experiences so there is less

misunderstanding

about the assignment's goals. Instead of simply demonstrating a new

process,

we give every student a chance to learn the process with hands-on step-by-step procedures. They'll get to plan ideas and play around

before

we expect them to create something called art. They'll learn to develop

preliminary ideas before they start on the main project. It teaches

students to work more like real artists.

Recently, while visiting with an art major at a nearby university, I asked her how she generally gets the ideas for her work. She replied, "I do research." I asked, "What kind of research?" "I look at artists' work until I find something that I like." I understand where she is coming from, but I am sad. She has learned well what most of us teach. Borrowing is easy. Original thinking based on our own experiences is really hard work. As a teacher, when I don't show examples before the work I am forced to think about the assignment, understand it, know how it works, what I want learned, and so on. It challenges me to be a teacher, not merely a supply clerk. It may mean fewer finished products, but isn't it better to foster an honest understanding of art, learning how to think, and self worth? Fewer end products can mean more learning. When students solve problems themselves, we find out how well we actually articulate the assignment. We also learn more about the diversity of our students. When students solve the problems, and ideas come from the students, we learn how unique our students are. This can be a bit disconcerting and can even look like regression if we are accustomed to seeing fairly skilled homogeneous mimicking of examples. In a product centered philosophy it seems stupid to reinvent the wheel. In a process centered curriculum where students learn how to think, the invention of a wheel would be a huge accomplishment. For too long we have taught to do and not to see. We have taught to do and not to understand. We have taught to do, but not to own - merely borrow. We have taught to do, but not to feel. When we show examples first, we dishonor the artistic process. When we show examples first, we rob the student's ability to own the solution. When we show examples first, we imply unreal expectations on the end product. When we show examples first, we unknowingly corrupt the process of producing meaningful self-expression. Let the end of each period be a benediction on today's learning. Let's endorse what we have learned by discussing it. Furthermore, at the end of the creative time we can show the work of real artists who have struggled with similar issues. What better way to close the session and help our students face the world? CONCLUSION RELATED TOPICS OTHER KINDS OF OBSERVATION DRAWING RITUALSBlind contours drawing is one of the basic ways to learn to draw. Using a blinder helps students practice. As students advance in their drawing skills, additional learning techniques are added to their practice routines. See this page for an explanation of all the skills that are needed in learning to draw. Art teachers, parents, and students themselves will want to use this as a check list. WHEN DOES DRAWING BECOME ART?This is not a simple question with a single answer. Drawing has uses as a planning tool, as a means to clarify an idea, to explain things, to aide in thinking, as documentation, and so on. When it is expressive and has aesthetic qualities, drawing becomes an art form as well. Gesture drawing is one example of observation drawing7 that is an opposite from contour drawing. Instead of slowly observing edges, in gesture drawing artists very rapidly and expressively draw from the center instead of from the edges. Gesture drawing frequently expresses motion and intensity of action. Like a jazz player whose body understands how to produce expressive sounds around a melody, the artists in the act of gesture drawing feels the pressure of the tool on the paper. Responding to both internal and external awareness, the artist makes a variety of expressive marks rendering and developing a drawing. After practice rituals in both contour and gesture drawing, students who are encouraged to experiment with combinations of styles within a single drawing may begin to understand the immense expressive and artistic potential in drawing. Students discover individual ways to express universal and common concerns. Artists also often draw dreams, imaginary content, inventions, memories, abstract patterns and designs, representations of sound, of tactile sensations, of taste, and so on. As we drawing becomes creative and expressive it become art. Art is a journey, not a destination. Many rituals and kinds of practice help us realize that we are on the journey. CITED REFERENCES 1Edwards, Betty. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. Los Angeles: J. P. Tharcher, Inc. 1979. 2Sherer, Lon. Practicing: A Liturgy of Self-Learning. 1988. Pinch Penny Press, Goshen College, Goshen, IN. p. 17. 3Chase, Marilyn. "Inner Music, Imagination May Play Role in How the Brain Learns Muscle Control," The Wall Street Journal, October 13, 1993, pages 1 and A13 4Rueschhoff, Phil H. and Swartz, M. Evelyn. Teaching Art in the Elementary School. New York: Ronald Press, 1969. pages 45 - 46. 5Tyson, Peter. "Daniel Glaser's Latest Study With Ballet and Capoeira Dancers." NOVA Science Now - January, 2005 6Nose drawing. This is air drawing where the nose is used as a pointer. It is not actual drawing. Air drawing is done before actual drawing in order to practice better observation. The method of nose practice was submitted by Naida Leon, a Florida art teacher. She was told to use this method as therapy for a six-year-old child with an eye that drifts out. She and I both find that children enjoy this while learning to observe better. 7Gesture Drawing is described in greater detail on my page titled "Portrait and Figure Drawing." On that page, see Inside-Out Gesture Drawing. Gesture Drawing is also explained in Wikipedia (referenced Sept. 4, 2008)

Biography of the author This paper was originally published as "ART RITUALS IN THE CLASSROOM" written by MARVIN BARTEL, Ed.D., Emeritus Professor of Art, Goshen College, copyright, © 1993, Photos - © 2001 This Update - © August 21, 2010 by Marvin Bartel. Original HTML editing by Lon Sherer, Emeritus Professor of Music, Goshen College What do Art Teachers say after trying the ideas in this essay: "I'm writing because I have found great information from your web pages, about teaching art! Since it had been quite a long time since I received my education, I was trying to brush up on what was needed to teach art. In searching for information on the web, I found your pages.

GOSHEN COLLEGE SUPER BOWL COMMERCIALS

|