Pregnancy Loss and Visual Expressions of Grief: An Examination of Frida Kahlo

Quietly the grief

loudly the pain.

The accumulated poison

love faded away

Mine was a strange world

of criminal silences

of stranger’s watchful eyes

misreading the evil.

darkness in the daytime…

Was it my fault?

I admit, my great guilt

as great as pain

it was an enormous exit

which my love went through.

—Frida Kahlo, from her diary

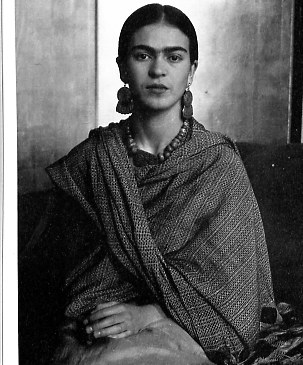

Frida Kahlo had a relationship with tragedy that is almost unparalleled. The Mexican painter began this relationship at a fairly young age—when Kahlo was eighteen, she suffered near fatal injuries from a bus accident in which a section of metal handrail pierced her body. The accident left her with a broken spine and collarbone, several broken ribs, a dislocated shoulder many fractures in her right leg, and a broken pelvis. She mostly recovered from these physical injuries, but her broken pelvis created a plethora of physical and psychological repercussions. The damage was such that Kahlo was unable to have children, and her attempts all ended in miscarriage and grief. Her pelvic injury served as a prelude for her traumatic reproductive life—three miscarriages, one of which caused severe hemorrhaging, and a lengthy recovery. However, Kahlo did not let her reproductive tragedies consume her entire life. Instead, she examined and worked through her experiences in her paintings. Therefore, by examining her work, we get an understanding of how she experienced the grieving process. But more than that, we can use Kahlo’s work to map a visual vocabulary that those experiencing the grief of pregnancy loss can employ to express their own grief.

Similarly, one can better understand Kahlo’s grieving process through her images by comparing her images to the traditional stages of grief; in the same way, others may better understand their own grieving processes through viewing and understanding her work. Yet one must be careful in using Kahlo as a universal example for all women who have experienced pregnancy loss. Cultural, socioeconomic and political identities have an enormous impact on any woman’s experience, and to ignore these differences is akin to ignoring gender difference in pursuit of a masculine universal. Following the use of Kahlo as an individual rather than a universal, one finds that she had many qualities that could separate her from other women. Kahlo was an ardent Communist, whose political beliefs of class abolition and planned economies would be a stark contrast to those of a constituent of a democracy. Her Mexican heritage emerges in a majority of her paintings, and she strongly identified with her indigenous ancestors and pre-Columbian culture. Some other characteristics that may alienate Kahlo from other women’s experiences are her bisexuality, her occupation as an artist, and her reproductive experience. However, Kahlo still is one of the only major artists to directly communicate her reproductive grief through visual art. Her grief is personal, and her experience with pregnancy loss is personal, but that doesn’t mean others cannot relate to her work. In fact, studying her work may provide others suffering from pregnancy loss—whether artists themselves, art scholars, or non-artists looking for a way to express their grief—an invaluable expressive vocabulary.

Although studying Kahlo’s paintings over the course of her miscarriages provides no definite answers to her grief process, some telling patterns emerge. These patterns can be grouped into themes that seem to reveal Kahlo’s grieving process after her miscarriages. Baby imagery, a desolate or claustrophobic use of space, the “floating Frida” effect, and the appearance of vines/umbilical cords all seem to represent different stages of the grieving process.

Kahlo’s very realistic and anatomically correct depictions of fetuses and the biological process of reproduction seem to reflect feelings of denial and yearning. Because Kahlo did not have a baby of her own, she may have allowed herself to circumvent the loss by creating a new, painted baby that gave her an opportunity to imagine a world in which her baby was still alive. Kahlo, perhaps going through a process of denial, may have recognized either her own attempt to deny the loss, or a societal pressure to deny the loss, and used visual representations of babies and reproduction to combat these feelings of denial. Later, when appearances of babies merge into representations of her pets (often seen by Kahlo as her “children”), it does not seem to represent denial as much as yearning. Her use of pets and baby imagery in the subject matter of her work may indicate not only her denial during her grieving process, but perhaps the start of a means of dealing with that grief.

Kahlo’s use of space suggests more of a struggle with the grieving process. The alternating use of empty space and very claustrophobic space seems to provide a visual analogue to feelings of numbness and shock, feelings that are common to many people who have experienced pregnancy loss. . Visual impressions of numbness are quite evident in Kahlo’s bare background self-portraits, but also in works like Henry Ford Hospital. Although there are objects that occupy the picture plane, Kahlo is very small in relation to the bed, and the bed is fairly small and separate from the rest of the painting. The floating bed also implies a sense of detachment or listlessness. Kahlo does not relate to the rest of the world, and instead, seems to lose herself into nothingness. In contrast, the tight, claustrophobic space created by the dense, jungle backgrounds in her later self-portraits appear to force Kahlo’s image out of the picture plane and at the viewer. Rich detail and patterns completely fill up the picture plane, and present a very stark contrast to the very empty and bare backgrounds of her earlier self-portraits, in which Kahlo is isolated. This suffocating movement is dramatic and sudden, and could be one way to represent the experience of shock. Kahlo may have felt like she was thrown into a situation over which she had no control, so she in turn throws herself at the viewer.

Kahlo’s grieving process continues with her placement of body. In many paintings, Kahlo does not look as if she is physically connected to the ground. Instead, she floats delicately, hovering slightly above the ground. Many sufferers of pregnancy loss mention feelings of disconnection, even out-of-body experiences. These same feelings of disconnect are shared by sufferers of depression, a common stage of grief. The floating begins as early as Frida and Diego Rivera, a painting that roughly coincided with her first miscarriage. It becomes more pronounced in works like. The large traditional skirts that Kahlo liked to wear may contribute to this floating effect, but the disconnected feeling remains. It looks like Kahlo felt separated from the rest of the world because of her pregnancy losses and because of her grief. Perhaps her visual representation of her disconnect helped Kahlo understand her own feelings of depression.

Lastly, the manner in which Kahlo uses flowing lines to either connect or disconnect may correspond to her process of finding resolution to her grief. The process of change in the depiction of roots may reflect on Kahlo’s integration of her pregnancy losses into the rest of her life. As the vine-like lines become more solidly connected to the world around them, so too does Kahlo become more connected with her grief, and draws closer to resolution. These lines appear as vines, umbilical chords, ribbons, or blood vessels, but all share the same fluid, coiling quality. These lines appear to have a very direct connection to Kahlo’s development towards resolution. The connectedness of the lines seems to show progress toward resolution. For example, in perhaps one of her most incredible self-portraits, Roots, the vines take root, and securely reconnect Kahlo with the Earth. In this painting, Kahlo reclines comfortably as a multitude of tangled roots erupt from a cavity in her chest. It has been called a “childless woman’s dream,” most likely because the roots come out of her womb, and extend out into the world. A child is one of the ways a parent continues her or himself, but Kahlo replaces the children with vines. The vines have also been seen as umbilical cords, which suggests that the vines connect Kahlo to the earth, implying that Kahlo is giving birth to the earth itself. No matter which interpretation one uses, it is clear that the lines in Roots, a painting from later in her career, are far more connected and grounded than the lines in some of her early paintings, such as Henry Ford Hospital.

Despite these clear echoes of reproduction, Kahlo had many reasons other to continue to grieve throughout her life, from her husband’s infidelities to her debilitating injuries and illnesses. These themes of grief could be a result of any number of different traumas. It is therefore empirically impossible to discern if the grief revealed in any given painting is due to her miscarriages or another loss in her life.

The study of art history is often seen as an “ivory tower” endeavor, which produces research that is valuable or applicable to a select view in the same field. However, the use of Kahlo’s work to map a visual vocabulary that those experiencing the grief of pregnancy loss can employ to express their own grief has a number of real-world applications. First, it brings attention to the silence that surrounds pregnancy loss; by discussing Kahlo’s experience, we move one step closer to ending the silence. It also validates Kahlo’s experience, and recognizes her pregnancy losses as significant. But most importantly, it could give women who do not have the artistic background that Kahlo did to use visual expression to work through their own grieving processes. These women can look to Kahlo as an example of a peer who successfully used visual expression to describe her miscarriages, and perhaps have hope that they may be equally successful. If women who are not artists have trouble expressing themselves through visual images, they can use Kahlo’s visual vocabulary to express their own experience. Similarly, her work may be useful to tailor art therapy sessions to the grieving process from pregnancy loss, and provide women with more specialized support. Finally, the study of Frida Kahlo may lead to similar studies of other artists who have experienced pregnancy loss to see how they express their grief either similarly or differently. Other major female artists, amateur artists who do not paint for the public eye, men whose partners have suffered pregnancy loss—all have unique perspectives on the grieving process from pregnancy loss.