Physics of Music—Matthew Rody

The Effect of Mouthpiece Design on Tone for the Alto Saxophone

A project completed by Matthew Rody for Physics of Music, Instructor: John Ross Buschert

Overview: The goal of this project was to attempt to quantitatively analyze the tone of an alto saxophone when using different mouthpieces. (Note that here tone is meant in the purest physical sense, really concerning only the make up of the sound produced in terms of harmonics.) The approach taken was to analyze sound samples of a saxophone being played and take data by recording the loudness (in dB) of each of the harmonics present in the sound to obtain a harmonic spectrum.

I. Introduction – A brief look at how saxophone mouthpieces work

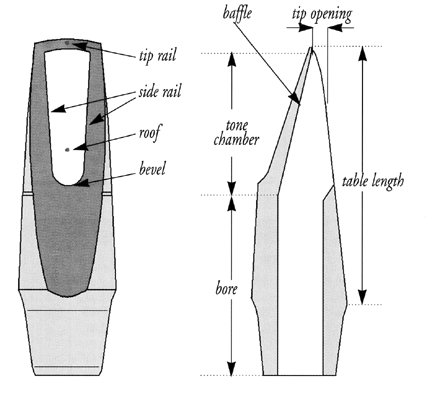

The saxophone mouthpiece is where the initial vibrations that produce sound in the instrument are created. The reed is placed on the flat surface of the table where it is held in place by the ligature. (To see a picture of the full mouthpiece setup, see this link [link to setup pic.jpg].) At a certain point near the tip, however, the table is no longer flat, and what is called the facing curves away, allowing the end of the reed to vibrate back and forth. Air moving past the vibrating reed the moves into the tone chamber and then on into the bore where the mouthpiece is connected to the body of the instrument via a cork neck.

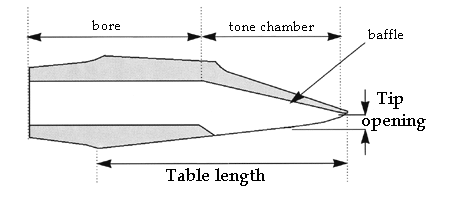

The two main mouthpiece features to note here are the facing and the chamber characteristics. Let us first consider the facing. The facing essentially consists of the table length and the tip opening.

The table length is effectively what controls how much of the reed is vibrating. A shorter table length leaves more space for the reed to vibrate and in doing so makes lower notes easier to play. The drawback is that higher notes are more difficult to play and pitch is harder to control. A longer table length means less space for the reed to vibrate, giving more pitch control and ease of playing high notes. Lower notes are harder to play, however.

The tip opening is the distance from the tip of the mouthpiece to the tip of the reed. The larger the tip opening, the louder one can play, but the cost is some responsiveness to the player (i.e. how easy it is to play). Mouthpieces with smaller tip openings are easier to play but cannot be played as loudly. Jazz musicians generally choose mouthpieces with larger tip openings so that they can be heard among louder brass instrument. By contrast, chamber musicians usually choose smaller tip openings for better blend. (A typical facing chart [link: facing chart.jpg] shows the wide range of tip openings available.) The most important thing to note hear is that the various aspects of the mouthpiece facing affect primarily the instrument response and do little to affect the actual tone produced by the instrument.

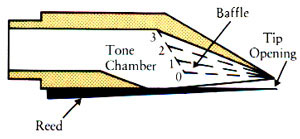

Next we shall consider the chamber characteristics. We will first look at the chamber size. In general, larger sized chambers emphasize the lower harmonics produced, giving a “darker” tone, while smaller chambers bring out the upper harmonics more, helping to create a “brighter” tone. This is why jazz mouthpieces generally have smaller chambers.

Another method of changing the sound produced in the tone chamber is the introduction of the baffle. As can be seen in the diagram below, the baffle is generally wedge-shaped, and can be a variety of sizes.

The baffle works by creating a smaller path for air to flow from the mouth to the tone chamber, thereby increasing the air speed. Smaller or no baffle emphasizes the lower harmonics, while a larger baffle brings out the upper harmonics. A picture of an actual baffle in one of the mouthpieces used in the experiment can be seen below.

II. Experiment – description of materials used as well as methods for gathering data

A Selmer model AS110 alto saxophone was used for this experiment, in conjunction with a Vandoren 3 1/2 Java reed. Five different mouthpieces were tested (see above): a Selmer C*, a Meyer 5M, a Meyer 6M, a David M. Knox Custom, and a Claude Lakey 4*3. Samples were recorded using an Audio-technica AT3031 microphone and using Cool Edit Pro 2.1 software. Samples were recorded as a single note (A#4) starting quietly and slowly growing louder. (Listen to the actual recorded samples used here: [links to: Selmer example, Meyer 5 example, Meyer 6 example, Knox example, and Lakey example.wav]) The frequency analysis feature of Cool Edit Pro was then used to obtain a harmonic spectrum for each of three dynamic levels for each sample. (Examples of raw data collected from a single dynamic can be seen here [links to: selmer spectrum and knox spectrum.jpg]) The three sets of data collected for each mouthpiece were then averaged to give on general characteristic harmonic spectrum for each mouthpiece. It was these averaged harmonic spectra that were then analyzed comparatively.

III. Results – a comparison of the harmonic spectra found for each mouthpiece

Below is a diagram showing the harmonic spectra for all five mouthpieces. On the x-axis is the harmonic, or what multiple frequency of the fundamental is being analyzed. The y-axis shows the loudness in dB of each harmonic for each mouthpiece. The spectra have been shifted so that the loudest harmonic for each spectrum is shown as 0 dB.

There are several important observations to be noted here. The first is that when comparing the harmonic spectra of a classical mouthpiece (such as the Selmer C*) and a jazz mouthpiece (such as the Knox Custom), there is a noticeable discrepancy between the relative loudness of all harmonics beyond the 4th.

This is especially noticeable when comparing the 5th harmonic which spikes up again for the jazz mouthpiece while the relative loudness for the classical mouthpiece continues to decline. What we are seeing is consistent with what was described in the introduction, as the larger chamber of the Selmer C* should give it much more emphasis in the lower harmonics. The Knox Custom, which has a smaller chamber, then has much louder upper harmonics which would be expected.

Next we should consider the effect of the baffle. For this comparison we shall examine the harmonic spectra of the Knox Custom (which has a baffle) as well as the Meyer 5M (which has an open, round chamber with no baffle).

As both of these mouthpieces are jazz mouthpieces, their spectra line up more closely than the Knox versus the Selmer, but there is still a noticeable difference in the loudness of the higher harmonics. The Knox Custom clearly provides a much greater presence of these harmonics in the tone it creates. Again, considering what we have learned of baffles, this is consistent with what we would have predicted: the introduction of a baffle in the mouthpiece chamber will further emphasize upper harmonics.

One final comparison to note is this: When we look at the harmonics spectra of the Meyer 5M and the Meyer 6M, we note that they are very similar.

Why is this? The answer lies in the difference between the two mouthpieces. In the mouthpiece name, the manufacturer indicates the relative chamber size with a letter (M for Medium) and the tip opening with a number (see facing chart [link: facing chart.jpg]). The two mouthpieces we have here, then, are different only in their tip openings which, as we stated in the introduction, affect primarily the response, not the tone generated. With this in mind it is logical that the spectra generated for these two mouthpieces should look so similar.

IV. Conclusions

Summed up, what we have demonstrated through this experiment is this:

1) The relative chamber size affects the tone of a saxophone. The larger the chamber, the more the lower harmonics are emphasized (creating a “darker” tone), and the smaller the chamber, the more the upper harmonics are emphasized (creating a “brighter” tone).

2) The addition of a baffle to the tone chamber of a mouthpiece does yet more to emphasize the upper harmonics.

3) While the tip opening of the mouthpiece may affect the response of the instrument, it does little to affect the tone produced.

Special Thanks to: Josh Ewert and Nate Grieser, for letting me borrow their mouthpieces.