Today is the last day we will be in Goshen before driving to Minnesota in the morning. Everyone in the group met at noon today to have their gear checked. Our group leader, Val Hershberger, knows a great deal about different pieces of gear and clothing.

Apart from the clothing for our time of service at Wilderness Wind, the gear needed for this trip needs to be very formidable for the area. Even though the weather forecast is saying the Waters will be 60˚F and sunny while we are canoeing, rain or high winds can drastically change the course of the trip.

Not to mention the water temperature.

Simply enough, Hershberger has instructed us to pack with the mentality of three layers: base, middle, and outer. Obviously, a rain coat and rain pants are essential, but the trick is to stay warm without freezing from sweating under every layer. Moisture-wicking base layers will be the solution for this.

The Waters either currently are or recently were covered in ice, so I need to keep my feet warm and dry. Waterproof hiking boots just won’t cut it, so I’ve packed a pair of rubber boots designed to insulate in temperatures as low as -40˚F.

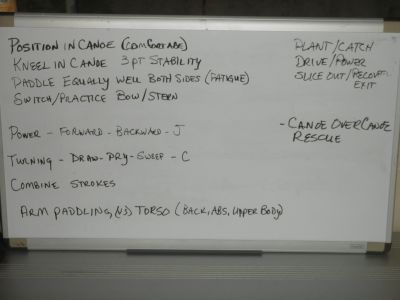

After everyone in my group had their gear checked out, it was time to learn the proper techniques of lake canoeing. River canoeing and lake canoeing are totally different, in that the amount of coordination required by everyone in a lake canoe is crucial for endurance and efficiency.

We drove over to Goshen Middle School, carrying a canoe on top of Hershberger’s CR-V. The middle school also has a canoe, which we used for our practice. Hershberger explained the basics of canoe terminology and paddling techniques. After practicing our strokes, we learned how to respond when calamity strikes.

One of the rules of the Boundary Waters, for anyone registered to be on the lakes, is that groups cannot be comprised of more than nine people and two canoes. Since our group is going in four canoes, we will be split into two groups. This ends up being the most ideal and safe way to rescue a swamped canoe.

Since we are carrying all of our own gear in our own canoes, it is important to remember in a tipping situation that saving the gear is not as important as saving the paddlers–especially in 35˚-50˚ water.

By traveling in pairs, this allows us to avoid resorting to the Capistrano Flip or the Fontaine Flop, which are methods of flipping and reentering single canoes without the help of another. What we practiced instead is referred to as a “canoe over canoe” rescue.

Logan Miller and Logan Steingass practice rescuing Emma Patty and Rebekah Steiner’s swamped canoe, forming the “T” shape.

When one canoe tips over, the other canoe paddles over to the swamped one to make a “T” shape with it. Meanwhile, one of the people treading water pushes down on the far end of the downed canoe (or the bottom of the “T”) to lift the other end, while the people in the upright canoe pull it on top of their canoe.

Once the downed canoe is on top of the upright one, the canoe is flipped, pushed back into the water, and aligned parallel with the other canoe so that the people treading water can jump back in.

The process seems complicated, but after a few practice runs we got the hang of it.

Holding the paddle in my hands again was simply refreshing, and actually practicing a canoe rescue like this is a lot of fun–though doing it out on the water certainly wouldn’t be. Even just practicing with 70 lb aluminum canoes is enough to wear someone out, but thankfully we will be using Kevlar canoes in Minnesota with roughly half the weight.

Our gear is packed, I’m a little low on sleep, but tomorrow at 5:30 A.M. we will begin the 12 hour drive North to begin our adventure.