What happens when thirteen eager Goshen College students step off an Amtrak train in Albuquerque, New Mexico to begin experiencing Indigenous cultures in the Desert Southwest?

We’ll let the students themselves tell you their stories…

Reflections from Julia:

We, the Hopi Navajo SST class, have been together since the beginning of May. Our first experience with the material was with David Lind, Professor of Sociology, who taught an introduction to Indigenous studies course. We studied the term sovereignty and its multiple meanings, learned about the Doctrine of Discovery, and learned some of the history between the U.S. government and Indigenous peoples. Then we delved deeper into the material with Sarah Augustine, a Pueblo (Tewa) woman, co-founder of the Suriname Indigenous Health Fund and the Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery Coalition. Augustine taught us about current events surrounding Indigenous rights. For example, we learned that in Oak Flat, Arizona there is a copper mining company currently attempting to mine on sacred Indigenous land, a constant threat to the Apache people who have been battling against it for a long time.

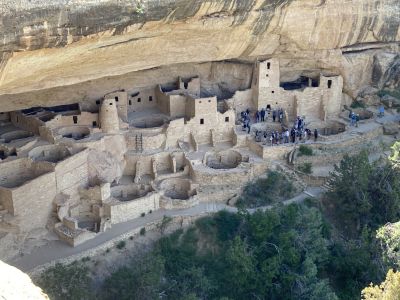

When our three-week class with Augustine ended, we jumped onto a train and traveled 30 hours to Albuquerque, New Mexico where we met up with Jerrell and Jane Ross Richer. Traveling north by bus we arrived at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, set up our tents and the following day started our class by hiking up a mountain. All of these events had one thing in common – we were alone together.

On our second day, when we visited Ancestral Pueblo sites, things were different. We were no longer alone, but were surrounded by the general public. Our experience began with a guided tour with 40 people, including 16 from the Goshen College SST group. We climbed down the mesa, up ladders, and through crevasses in the rock to make it to these sites.

We were all guided by Ian, a National Park Ranger, who has Pueblo ancestors, the very ones that resided in these ancient homes. He asked us to respect his ancestors — the birds, insects, and soil — reiterating the importance of having reverence before we enter the sacred place.

When Ian asked the group if there were any questions, one girl asked, “Are you an Indian?” Ian answered the question without hesitation by saying, “Why yes, I am!” Soon after, another little girl told him there was a dead bird in the corner and there was an awkward silence as no one knew what to do and a slight giggle from the tourists reverberated through the ruins.

After the hike, while in a museum that displayed ancient artifacts from sites around the area, I overheard a woman say to her daughter with a disgusted attitude, “What even is that? A spaceship?” as she pointed to a bowl titled, “Ancient Representation of Insects”. The prevalent theme of ignorance and disrespect across the general public was often difficult to swallow throughout our time.

It is easy to surround yourself with those who think, speak, and act like you, but it is hard to go outside of that comfort. It is easy to forget that others think differently or haven’t had opportunities to be educated about the reality of Indigenous people’s history and culture when you are surrounded by the same group of students, immersed in study for 6 weeks. So, in this instance, while surrounded by the general public, I was reminded why we are here.

This Hopi Navajo SST experience is not only an opportunity to become more educated ourselves, that is just the beginning, but it’s a chance to educate others beyond ourselves. It is an opportunity to expand the discussion of the truth and reality of Indigenous people’s lives, to dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery. It is our duty to take this knowledge and spread it because what we thought was truth before taking this class was not reality. Teaching others to recognize this is a huge step toward bringing awareness of the injustices faced daily by Indigenous peoples around the world.