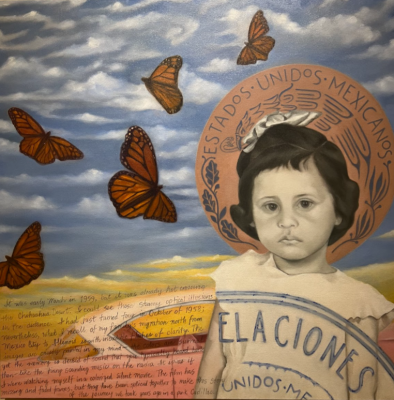

Today we began our day by visiting the National Museum of Mexican Art in Harrison Park. Art from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and current Mexican artists living in Chicago was displayed. The history, personal stories, and finding identity in a new land is depicted through these art pieces. Pilar Acevedo shares her migration story from Mexico to Illinois in her piece titled Al Norte in a Pink Cadillac/Going north en una Cadillac rosa. Acevedo was four years old when her family moved to the United States, but she remembers bits and pieces. She shares what she saw, heard, and felt and describes it “as if I were watching myself in a colonized silent movie.”

Pilsen is one of Chicago’s most recognizable Mexican-American neighborhoods which has seen a great number of Mexican immigrants settle and thrive within its streets. Sitting in Southwestern Chicago, Pilsen has changed a lot over the years as wealthy businesses and people slowly push within and against the boundaries of the neighborhood. What was once an incredibly strong and densely Mexican-American neighborhood is slowly becoming another victim of gentrification, causing it to lose its identity as one of the most densely packed Mexican immigrant communities in the United States. To counteract this loss of people, organizations such as the Pilsen Housing Cooperative are purchasing housing and removing it from the speculative real estate market in order to allow the Mexican-American community to purchase it at affordable prices, thus fighting against rising housing prices.

After the museum, tour guide Luis Tubens showed us around the neighborhood. Luis Tubens worked at the National Museum of Mexican for ten years, and now uses his knowledge to share the stories behind the murals in the neighborhood.Topics such as gentrification, freedom, love, religion, housing issues, fighting to stay, and many others were seen. In addition, we saw monarch butterflies, two volcanos (La Mujer Dormida and El Popocatepetl), the eagle/snake that appear on the Mexican flag, la Virgen de Guadalupe, the Cempasuchil flower used during Day of the Dead, and several other iconic symbols used to represent Mexican culture. Our tour guide explained that during the Muralist Movement, there were three main focuses. The revival of indigenous past, the truth of colonization, and workers’ rights.

The streets of Pilsen are still populated with generations of the Mexican-American community who are proud of their indigenous history and the struggle they have endured to plant themselves firmly in Chicago. Businesses such as the restaurant we visited, Los Comales, are still run by members of the Pilsen community. Additionally, there is a lot of strength among the businesses in Pilsen with a tortilla factory, El Popocatepetl Tortilleria, providing tortillas for the restaurants within Pilsen.

The movement of Mexican-Americans out of Pilsen due to the rising housing and living costs in the area due to gentrification has led to La Villita, or Little Village, to become the predominant Mexican-American neighborhood in Chicago. Unlike Pilsen, Little Village is much more open about its Mexican influence and culture. Architecture, businesses, flags, and artwork bolster its proud identity of a Mexican-American community. With an incredibly strong economic presence, being the second highest grossing shopping district in Chicago only behind Michigan street, Little Village may maintain its community in a way that Pilsen is struggling to do. As Pilsen continues to thrive and fight to maintain its roots, the various other Mexican-American communities’ successes and movement of people in and out of Pilsen may help the Pilsen neighborhood permanently establish itself as a center for Mexican-Americans in the United States.

After ending our day, we pondered about how we felt as first generation Mexican-Americans in Pilsen. This neighborhood was once a heavily decorated Mexican-American landmark however we did not see it in that light. At the time of our visit, we did not see a lot of people that looked like us, that sounded like us, or even sounds that we would recognize as Mexican-Americans. However, where we did feel most at home was within the walls of Los Comales where music, flavors, and language were all recognizable and loud. We could definitely feel that tension of losing that sense of home in the neighborhood. We are hopeful to come back one day and be able to witness a revival of the neighborhood that still holds a lot of value for the people there and the people of Chicago.

Aranza Jimenez Cruz, Javier Reyes