Arts in China

Today we post, with permission, excerpts from two student journals investigating the arts. In both cases they reflect on what they see as distinctive aspects, or Chinese characteristics.

Music and Performance in China

By Sam

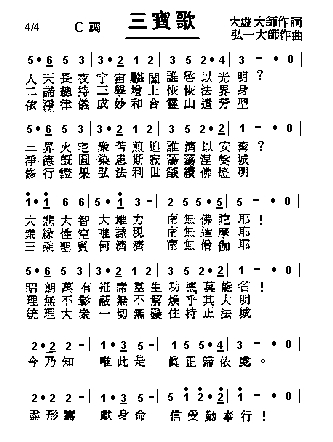

Something I’ve noticed about music practice and performance in China is that music [is] … read from a different type of score than we are accustomed to. I asked my Nanchong host dad about this and he said that this kind of score is a more traditional Chinese form of notation and is thus used with traditional Chinese instruments and voice. [Western-style scores are used when playing Western-style instruments.]

What’s fascinating to me about this traditional notation is that it requires a completely different mindset to read than Western notation. In the West our music is written and interpreted visually, as the relationship in physical distance between notes on the lines and spaces of a staff. In traditional Chinese notation, music is portrayed as a series of mathematical relationships between tones of a specific scale. There is no visual component, only a mathematical one. What’s more, there’s no sense of an absolute or constant pitch (like how the middle space on a treble clef is always a C) because the numbers written in traditional Chinese notation relate to a pre-determined key. Furthermore, this kind of notation doesn’t seem to have a way to deal with accidentals, notes that are not present in a key’s scale, which suggests that traditional Chinese music seldom (or never) deviated from a certain set of musical modes. This is fascinating because if one of us had tried to sing what the [Chinese] performers sang fro us, we would have been stymied by the notation, even if the song itself wasn’t that hard—we just don’t have the right mindset. …

I think that performance—musical or not—is much more commonplace in Chinese society than American. Even giving answers in a middle school English class is a kind of performance, with the student in question standing alone to give the answer. I think this is why we as SSTers are so often asked to sing songs, whether it’s in class or in public; the Chinese think nothing of such a performance while we are quite concerned with the idea of standing up and singing by ourselves. Still, I have had students in class here in Guang’an who hide their faces in their hands in embarrassment when called upon to give the answer to a question they don’t know. It seems odd to me because I would rather they just say “I don’t know” so we can move on, but with the performance mentality, not knowing an answer in class is almost as embarrassing as screwing up a solo in orchestra rehearsal. I wish this was not the case in the classroom, but I imagine that with so many opportunities to practice “performing” in normal life, Chinese people must think us strange for being so shy by their standards.

Calligraphy

By Vince

We visited a Chinese calligraphy studio the other day. Located somewhere in Guang’an and pandering to students of various ages, the studio is funded by the government. It is part of the Deng Xiaoping library, and provides a free opportunity for calligraphy education on the weekends. When we arrived there was a class of younger children, but they also serve people high school age and beyond.

The tables are covered in soft mats peppered with ink stains. Brushes of various sizes and widths hang on racks and rest on the edges of bowls of ink. As we look around and try our shaky hand at copying from some models, many pictures, naturally, are taken.

Along one wall, a long, red banner is hung, encouraging students to “Learn Calligraphy from Grandpa Xiaoping.” Beneath this, there are calligraphic works in various styles and in various stages of completion adorning the walls. Some seem freshly finished and are hanging up to dry. Others are completed, mounted on intricate scrolls or framed.

The works vary in style as well, from the earliest “oracle bone” style to the clerical “li shu” style, which is more readable; and from modern regular script to flowing cursive script; which is illegible to all but the most trained eye. It is this last style that tends to be the most bemusing for foreigners since it appears to our untrained eye to be sloppy. But for Chinese people and calligraphy experts, it seems to be the pinnacle of artistic form. Works in this cursive “running grass style” were described to us as being real art, not just pretty renditions of words on a page.

Like Western calligraphy, the best Chinese calligraphy is considered to be a work of art, but the similarities seem to stop there. Especially in the cursive script there is an emphasis on natural flow between strokes, radicals, and even characters. This is loosely reminiscent of the idea of Qi in traditional Chinese medicine: energy must be allowed to flow.

Balance is also an important attribute of good calligraphy, and one that closely resembles the traditional ideals of yin and yang. On the simplest level, there must be proper balance between the black of the ink and the white of the paper. This, as the teacher here pointed out, is one of the simplest ideas to understand, but the most difficult to implement, setting good calligraphy apart from average calligraphy.

Red seals, with names or happy messages engraved in a Qin dynasty script, can help with the balancing process. In areas with large white space, a seal might be placed to restore balance.

In cursive style works, some characters are heavy bold, with bleeding ink, while others the brush was so dry that characters are barely legible. By western standards, this is ugly, but a contrast between wet and dry, dark and light, is actually desirable.

In learning, models are copied and styles are learned by rote. But, interestingly, at the highest level, a piece is judged by its emotional content, and can provide insight into the author’s mood at the time of writing.