Foreword

By John D. Roth

The history of the Mennonite church in Indonesia nearly always begins with the story of Pieter and Wilhelmina Jansz, who arrived in the coastal town of Japara, Java, in 1851 as representatives of the Dutch Mennonite Mission Board. By all accounts, they were innovative and gifted missionaries. In 1854 Pieter baptized a group of five Javanese believers, marking the official birth of the Muria Javanese Mennonite Church.

As we now know, however, the true origins of the church were more complicated. A fuller account of that story must include a central role for Kyai Ibrahim Tunggul Wulung (ca. 1800-1885), a Javanese mystic and prophet who transformed a gospel expressed in a European idiom into images, concepts, and practices that made sense to the Javanese people. Tunggul Wulung envisioned the church as self-sustaining Christian communities, freed from the burdensome labor obligations imposed by the Dutch government and committed to preserving Javanese culture, language and folkways. In a jungle clearing in Bondo (Jepara), Tunggul Wulung helped to establish the first of several Christian settlements in Java that marked the true foundations of the Muria Javanese Mennonite Church.

Since then, the basic outline of that story—the “enculturation” of the gospel into terms that made sense within local contexts—has been repeated in settings around the world. During the first half of the twentieth century Mennonite missionaries from Europe and North America left a significant legacy—sharing the gospel, planting churches, and creating schools, hospitals, and relief organizations in many settings around the world. But in each instance, significant growth happened only when local leaders assumed responsibility for the future of the church and began to translate the gospel into their own cultural context.

The results in the second half of the twentieth century have been profound.

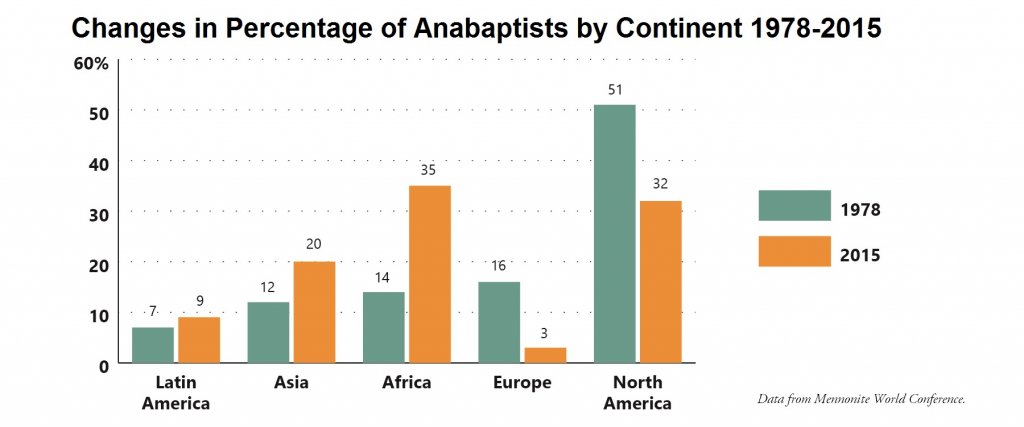

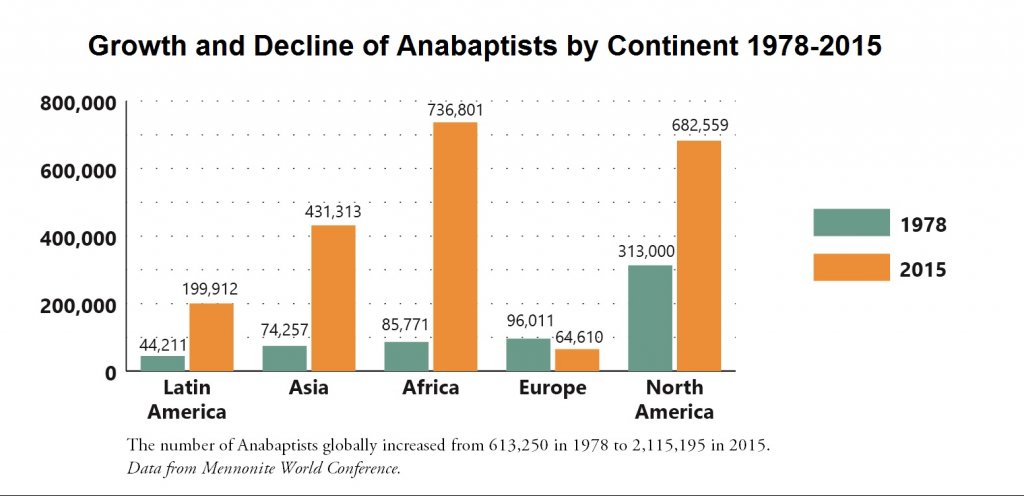

In 1978 Mennonite World Conference estimated that there were 613,000 Anabaptists in the world, with the majority of them (67%) living in Europe or North America. By 2015, less than four decades later, that number had more than tripled to a total church membership of 2.1 million Anabaptists. Today, Europeans and North Americans account for only 36% of the global Anabaptist-Mennonite church, with the vast majority living in Africa, Asia and Latin America—the so-called “Global South.”

From the perspective of a 500-year-old tradition, this transformation is the single most important event in the history of the Anabaptist movement. It marks a profound reorientation, whose significance we are only slowly coming to understand.

In 2012 I helped to establish the Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism (ISGA) as an effort to focus the academic resources of Goshen College (Goshen, Indiana, USA), long a center of Anabaptist studies, on this new phenomenon of “global Anabaptism.” The Global Anabaptist Profile—a project initiated and carried out by the ISGA—is the first representative survey of global Anabaptist-Mennonite churches.

History and Methodology of the Global Anabaptist Profile

The original vision for this project emerged out of conversations in 2009 with Conrad L. Kanagy, a sociologist at Elizabethtown College, and Richard Showalter, then president of Eastern Mennonite Missions (EMM). With strong support from Showalter, Kanagy had just completed a church member profile of twelve church conferences that were affiliated with EMM. In 2010 I attended a consultation in Thika, Kenya, to review the findings of the project alongside church leaders from participating groups. I was deeply impressed by the level of conversation and new insights that emerged from that gathering. (The results of that study appeared as Conrad Kanagy, Tilahun Beyene, and Richard Showalter Conrad Kanagy, Winds of the Spirit: A Profile of the Anabaptist Churches in the Global South (Harrisonburg, Va.: MennoMedia, 2012)).

Inspired by this project, I approached the Mennonite World Conference (MWC) Executive Committee in 2011 with a proposal for a broader survey that would be more representative of the global Anabaptist-Mennonite fellowship. I am deeply grateful to Danisa Ndlovo, then president of MWC, César García, MWC general secretary, and the Executive Committee for agreeing to collaborate with the ISGA in this project. The goals of the “Global Anabaptist Profile” included the following:

- To provide participating churches with information to guide their mission and priorities.

- To strengthen relationships among MWC churches.

- To inform the development of MWC priorities.

- To establish a baseline against which to measure future change.

- To train leaders to conduct church profiles in the future.

- To strengthen a sense of Anabaptist-Mennonite identity among participating groups.

After a year of fundraising and many consultations with Mennonite mission agencies, Mennonite Central Committee, various church leaders, and a group of sociologists who had experience in conducting cross-cultural surveys, we identified a list of MWC churches who would be invited to participate in the Global Anabaptist Profile. All full members of MWC who had 1000 or more members were considered for the sample. Of the 67 groups who met that criteria, 24 were selected through a stratified sampling process, with proportionate representation among MWC’s five continental regions. We then invited leaders of those groups to join the study and to appoint a local Research Associate who would carry out the survey in their context.

In August of 2013 the Research Associates and other collaborators (30 people from 19 countries) met at Goshen College for a week-long consultation. Together we finalized a questionnaire based loosely on the MWC “Seven Shared Convictions,” working carefully on the wording of each question. The seven-page survey included questions on demographics (e.g., age, gender, marriage status, etc.) as well as Christian doctrines and practices (e.g., church participation, religious identity, beliefs about Jesus, Scripture, witness and evangelism, peace and social justice, etc.). Together we also reviewed research methodology, created an interview protocol, and discussed details related to data entry. From a comprehensive list of congregations submitted by each Research Associate, we then randomly selected a set of congregations for participation in the project.

During the next six months, the questionnaire was translated from English into twenty-five languages, and then back-translated into English for comparison with the original to ensure accuracy. (The languages included: Afrikaans; Amharic; Bahasa; Chichewa; Chishona; Dorze; English; Enlhet; French; German; Hindi; Javanese; Kikongo; Lingala; Oromo; Portuguese; Russian; Sindebele; Spanish; Swahili; Tagalog; Telugu; Tshiluba; Tumbuka; Xhosa; Yao.) Once the translations were completed, Research Associates visited or made direct contact with each of the selected congregations, inviting all members above the age of eighteen to complete the questionnaire, usually in the context of a congregational gathering.

Collecting the Data

By the middle of 2015 the data gathering stage was nearly complete. The response rates of congregations who agreed to participate in the survey, as well as the response rate of members who completed a questionnaire, varied substantially from conference to conference.

In the Global South (Africa, Asia, Latin America) 87% of the selected congregations participated as compared to 71% of congregations in North America and in Europe (Global North). In nine conferences, all of them in the Global South, 100% of the congregations in the original sample participated in the Global Anabaptist Profile by completing questionnaires.

The highest response rates for members also occurred in the Global South, where 31% of members from the original sample completed questionnaires as compared with 19% of members in the Global North. Altogether, the Global Anabaptist Profile includes data from 18,299 respondents representing 403 congregations, 24 MWC conferences, 18 countries, and 5 continents.

Challenges and Limitations of the Survey

As with all major research projects, the Global Anabaptist Profile faced a number of significant challenges, beginning with the design of the questionnaire itself. We wanted the survey to provide basic demographic information as well as insights into the beliefs and practices of a wide cross-section of MWC-member groups. Creating a survey to quantify such things accurately is difficult in the best of circumstances, but it is even more challenging to do so in cross-cultural settings where groups express theological and ethical convictions in very different ways. Some of the questions in the survey were borrowed from other research projects, while many more were developed or refined through careful conversation with Research Associates at the consultation in the summer of 2013.

Inadequacy of Survey Questions

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the strongest criticism of the survey came from a European group—the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Mennonitischer Gemeinden (AMG) in Germany. Although their Research Associate was present at the consultation and they participated in the survey, AMG leaders later expressed deep frustration at several specific survey questions, arguing that they seemed to reflect strongly evangelical understandings of Christian doctrine that were foreign to their context. For example, none of the options presented in a question related to the Bible adequately described a response that most members in their group could easily affirm. Church leaders expressed similar frustrations about questions related to the atonement, or attitudes toward people of other religions, or the use of the phrase “born again,” insisting that the questions were not framed in ways that aligned with their theological perspectives. These frustrations were certainly understandable: quantitative surveys are inherently limited by a finite number of possible responses, and abstract beliefs are difficult to quantify. Yet the questions appearing in the Global Anabaptist Profile reflected a collaborative process by the Research Associates who represented a cross-section of the global church. No other group who participated in the project expressed similar concerns.

Difficulty of Integrating the Interviews

Although the numerical results of a quantitative survey can be very illuminating, we recognize that the lived experience of the Christian faith in culturally diverse settings is not easily reducible to statistics. Thus, from the beginning we hoped to combine a quantitative approach represented by the survey with a qualitative component in which Research Associates would interview several members of each congregation to get a fuller picture of the life of the church. The interviews turned out to be only partially successful. Some Research Associates found it simply too time-consuming to add this additional task to their work; others had difficulty persuading members to participate, or they faced technological challenges with the recording equipment. (The ISGA provided each Research Associate with a small hand-held digital recorder, easily rechargeable, whose sound files could be downloaded to a laptop computer for storage.) Transcribing and translating the interviews proved to be another significant obstacle. In the end, the project generated 29 interviews in seven languages, which remain available for future researchers. But we have not integrated the interviews into our findings.

Logistical Challenges

Some of the challenges involved with the Global Anabaptist Profile were logistical. Research Associates in the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, faced significant difficulties in reaching remote congregations while traveling on unpaved roads. Communicating with rural congregations was not easy; and some local pastors were suspicious of the intended purpose of the survey. In some settings, a large percentage of church members were illiterate. Even though we had a protocol for including responses from illiterate participants, the process was time-consuming and cumbersome. Compounding this challenge was the fact that in some contexts more men tended to be literate than women, resulting in a disproportionate number of male participants in the survey there. Entering the data was also a labor-intensive and tedious task. Research Associates and their colleagues worked extraordinarily hard, but sometimes the steps were confusing and data needed to be re-entered.

The Global Anabaptist Profile does not claim absolute certainty in its description of a particular group’s faith or practices. The challenges of undertaking a cross-cultural survey, where experiences and assumptions differ widely, are real. The data that we present here is suggestive but not absolute. As with all surveys, the results call for an active process of interpretation and clarification, a task that started already on July 26-30, 2015 at a consultation of Research Associates and church leaders at Elizabethtown (Pa.) College.

That conversation will undoubtedly continue. The critique of the Global Anabaptist Profile by the AMG is part of that process; but we hope that discussions sparked by the results will also provide participating groups with opportunities for further reflection, and that the conversations emerging from those settings will lead to a deeper sense of theological identity, a more vibrant witness, and stronger relationships with other groups in the global Anabaptist-Mennonite family of faith.

Was it Worth the Effort?

In response to our early reporting on the results of the Global Anabaptist Profile, some noted that the overall outcome did not seem to contain any major surprises. It is true that the most significant differences in results tend to highlight the contrast between MWC churches in the Global North with those in the Global South, thereby reinforcing conclusions about differences in demographics, beliefs, and practices that are already generally well established. MWC churches in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, for example, are younger than those in Europe and North America; they tend to place a stronger emphasis on the gifts of the Holy Spirit, and their worship styles tend to be more expressive. Anyone who has read the work of Philip Jenkins or Lamin Sanneh on the broader trends in global Christianity is not likely to be surprised by these results of the Global Anabaptist Profile.

Nevertheless, the potential fruits of the Global Anabaptist Profile go far beyond these general observations.

- The results of the Global Anabaptist Profile provide significant insights into attitudes and practices related to the distinctive characteristics of the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition. On several of these distinctive emphases—e.g., concern for reconciliation and peacemaking; commitment to service; a view of the church as community—the survey revealed widespread agreement among churches in both the Global North and the Global South. The Global Anabaptist Profile also creates the possibility of continental and denominational comparisons, resulting in a more finely-grained analysis than just North/South comparisons. And the survey provides an important framework for testing or challenging the stereotypes that groups might have of each other.

- The survey provides churches, and especially church leaders, with specific information regarding their own groups. Most of the groups participating in the Global Anabaptist Profile had never taken part in a church member profile. This was their first opportunity to have a systematic overview of basic information about members, including beliefs and practices. The survey provides each group with a baseline for future studies that could reveal changes over time. And it gave Research Associates basic training in survey methodology that could be beneficial to their churches in the future.

- Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the Global Anabaptist Profile provides a framework for informed conversations among MWC member churches about specific beliefs and practices, especially where the study has revealed similarities or differences. The consultation of Research Associates and church leaders at Elizabethtown in July, 2015 generated enormous energy as representatives of each group presented their findings and joined with other participants in animated conversation in interpreting the results. Some church leaders, for example, expressed surprise at the level of support in their church for the ordination of women. Some noted with concern that members were not completely united on certain ethical practices. The responses to the question on persecution created a setting for personal sharing as church leaders recounted stories of courageous witness. At various times throughout the consultation we paused in our reporting to pray for a church that was confronting a particular challenge. While the Global Anabaptist Profile revealed some significant differences regarding theological emphases and church practices, those differences were also an occasion for listening and learning from each other.

The Challenges Ahead

Within the many detailed findings of the Global Anabaptist Profile several larger themes emerge that may have special relevance for MWC as it determines its priorities for the future.

Growing Churches . . . and the Need for Theological Education

The churches in the Global South tend to be relatively young, with a higher percentage of women in childbearing age than churches in the Global North. These churches are growing, either by virtue of large families or by mission outreach. At the same time, however, these growing churches often have relatively limited access to educational opportunities, especially to theological training from an Anabaptist-Mennonite perspective. The challenge of equipping and training young leaders will be a major concern for MWC in the future. The theological direction of MWC will be shaped by these decisions—if we do not help provide theological training that is accessible, affordable and appropriate to their circumstances, pastors of new congregations will find that training elsewhere.

Responding to Muslim Neighbors

The Global Anabaptist Profile makes clear that perceptions of Muslim neighbors vary significantly within our fellowship, a theme that became even clearer in our conversations at the consultation at Elizabethtown. Some MWC member groups have experienced direct persecution and regard Islam either as a threat or as the focus for missionary outreach. Other groups are working hard at identifying points of commonality with their Muslim neighbors, seeking to collaborate whenever possible. Although this topic was not a major focus of the Global Anabaptist Profile, it emerged frequently enough to merit more attention by MWC in the future.

Experiences of Persecution

Closely related was a surprisingly high percentage of MWC-member churches who reported experiencing some kind of persecution. Although the survey did not clarify the exact nature or extent of that persecution, the fact that so many groups identified this calls for more pastoral attention to the challenges some of our brothers and sister are facing in their witness to Christ.

Differences in Ethical Practices

All MWC member churches care about the ethical practices of their members—faith in Christ, we all agree, should bear fruit in a transformed way of life. But exactly how that commitment to following Christ is expressed in daily practices differs from group to group. We are not all united, for example, on the question of dancing or the use of alcohol; we have differences regarding divorce and remarriage; we are not in full agreement regarding Christian participation in government and politics; and we differ on how the gospel of peace is expressed in daily life. These differences are real. On the one hand, MWC is not a body that enforces uniform practice on its member churches. On the other hand, we value each other as brothers and sisters in Christ earnestly seeking to be faithful to the gospel. Do we have settings in which we can listen to each other? Can we continue to respect differences on these ethical practices? How important is it that we are all of one mind on these questions?

Differences in Understandings of the Holy Spirit

On the whole, church members in the Global South have broader and more frequent experiences with the charismatic gifts of the Spirit than those in the North. They also have a greater openness to the Holy Spirit speaking directly to individuals. And Anabaptist-Mennonites in the South are much more likely to think of God as the source of individual health and wealth. These differences have implications for differing approaches to worship, understandings of prayer, attitudes toward “prosperity gospel,” and assumptions regarding human agency that we need to acknowledge.

Negotiating Worldviews

Behind some of these differences are even more basic differences in how we look at the world. In some ways, MWC member churches reflect premodern, modern, and postmodern worldviews. Some groups, for example, regularly experience the living presence of the Holy Spirit in clear and tangible ways—as a spiritual battle between good and evil that finds expression in miraculous healings, deliverance from demon possession, and an openness to God’s revelation in dreams, visions and prophecies. Some groups reflect a more modern approach to faith, with a strong emphasis on the authority of carefully-worded confessions of faith, a literal interpretation of Scripture, a concern for clarity of belief and practice, and aggressive forms of mission. A smaller number of groups might be characterized as postmodern. They tend to focus on general themes in Scripture, place a stronger emphasis on individual experience in ethical questions, recognize the presence of God in all cultures, and advocate religious toleration. These distinctions between premodern, modern, and postmodern are rarely absolute; in fact, the lines between them are frequently blurred. But they do suggest different beginning perspectives that MWC will need to recognize as we live together as a body.

Visibility of MWC

Fifty-eight percent of respondents in the Global Anabaptist Profile have heard of Mennonite World Conference; but this awareness differs significantly by hemisphere: 75 percent of those in the Global North are aware of MWC as compared to 55 percent in the Global South. Europeans (88%) were most likely to have heard of MWC, followed by North Americans (72%), Africans (65%), Asians (53%), and Latin Americans (49%). These differences by hemisphere and continent point to the efforts needed to raise awareness of Mennonite World Conference among its constituent conferences. None of these challenges can be “fixed” with simple solutions. Addressing them will require courage, creativity, patience, and graciousness, and a deep trust in the presence of the Holy Spirit. Unity in the body of Christ is always a gift that we receive, not an outcome that we create through our own efforts. But we hope that naming some of these challenges will be a helpful step in our journey forward together in faith.

Acknowledgements and Thanks

This project has come to fruition only through the generous support of many individuals and groups. I am particularly grateful for the collegial expertise of my co-director in this project, Conrad Kanagy, professor of sociology at Elizabethtown College. Conrad brought to the Global Anabaptist Profile not only his considerable professional experience in conducting church member profiles, but also a deep love for the church in all its expressions. He has been a steady friend and guide at each step of the project. Elizabeth Miller, director of communications at the Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism, has also played a key role in the Global Anabaptist Profile. Elizabeth oversaw many of the complex logistical details of the consultation of Research Associates and church leaders at Elizabethtown College (July 26-29, 2015) and has been a wise, cross-culturally sensitive consultant as the project moved forward. Along with Conrad, Elizabeth was closely involved at each stage of production of this volume.

The project would not have happened without the dedicated work of the Research Associates (listed below). They were the face of the Global Anabaptist Profile in their local settings. Their dedicated, often sacrificial, efforts stand behind all the data presented here. By the end of the project, the team of Research Associates had become friends—brothers and sisters in the global family of Christ.

We have also been blessed with a remarkable group of student assistants, including: Amira Allen, Justina Beard, Danielle Mitchell, Jennifer Preston, Amanda Robinson, Emilee Rhubright, Angeliky dos Santos, Mara Weaver, and Alex Wildberger. In addition, I want express deep gratitude to Iris Martin for creating powerpoints of the summary reports, Antonio Ulloa for his detailed attention to cleaning and entering data as it arrived from the field, and to SaeJin Lee for her work in the design of the book. We are also were blessed with strong institutional support from Goshen College, Elizabethtown College, and the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies.

Each of the church conferences that participated in the Global Anabaptist Profile made a significant contribution to its success, either in labor or in other in-kind gifts, such as providing Research Associates with food and lodging as they traveled. Yet the project would have been impossible without the financial contributions of several key institutions and individuals. In particular I am pleased to name: Mennonite Central Committee, the Schowalter Foundation, the Fransen Family Foundation, Jon and Rhoda Mast, Virgil and Mary Ann Miller, Bob and Janie Mullet, Rick and Joy Hostetter, and Mark and Vicki Smucker.

At every step of the way, César García, general secretary of the Mennonite World Conference, along with other members of the MWC staff, provided crucial support. We are deeply grateful for the collaboration of MWC in this project, even though it should be clear that MWC bears no responsibility for the outcome.

The participating churches and Research Associates in the Global Anabaptist Profile are:

- Argentina (Iglesia Evangélica Menonita Argentina) / Delbert Erb

- Brazil (Aliança Evangélica Menonita) / Tiago Lemes

- Canada (Brethren in Christ Canada) / Roger Massie

- Canada (Evangelical Mennonite Conference) / Robyn Penner Thiessen

- Colombia (Iglesias Hermanos Menonitas de Colombia) / Diego Martinez

- Congo (Communauté Mennonite au Congo) / Joly Birakara Ilowa

- Congo (Communauté des Églises des Frères Mennonites au Congo) / Damien Pelende Tshinyam

- Ethiopia (Meserete Kristos Church) / Tigist Tesfaye Gelagle

- Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Mennonitischer Brüdergemeinden) / Jonas Beyer

- Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Mennonitischer Gemeinden in Deutschland) / Werner Funck

- Guatamala (Iglesia Evangélica Menonita de Guatemala) / César Montenegro

- Honduras (Organización Cristiana Amor Viviente) / Reynaldo Vallecillo

- India (Bihar Mennonite Mandli) / Emmanuel Minj

- India (Conference of the Mennonite Brethren Churches in India) / Chintha Joel Satyanandam

- Indonesia (Gereja Injili di Tanah Jawa) / Muhamad Ichsanudin Zubaedi

- Malawi (BIC Mpingo Wa Abale Mwa Kristu) / Francis Kamoto

- Nicaragua (Convención de Iglesias Envangélicas Menonitas) / Marcos Orozco

- Paraguay (Convención Evangélica Hermanos Menonitas Enlhet) / Alfonso Cabaña

- Paraguay (Vereinigung der Mennoniten Brüder Gemeinden Paraguays) / Theodor Unruh

- Philippines (The Integrated Mennonite Churches of the Philippines) / Regina Mondez

- South Africa (Grace Community Church) / Lawrence Coetzee

- The United States (Brethren in Christ Church in the U.S.) / Ron Burwell

- The United States (U.S. Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches) / Lynn Jost

- Zimbabwe (BIC Ibandla Labazalwane kuKristu eZimbabwe) / Jethro Dube