“Peace is not a quiet prison”: An interview with Professor Rob Brenneman

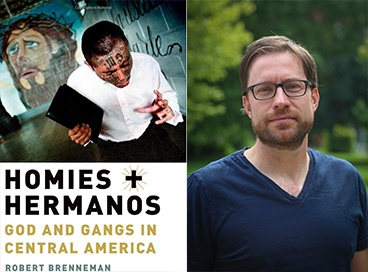

Meet Rob Brenneman, professor of criminal justice and sociology. He is in his third year as director of the Criminal Justice and Restorative Justice (CJRJ) major at Goshen College. Brenneman is also a world expert on the intersection of urban interpersonal violence and religion in Central America, more specifically Guatemala. He has even been called to testify in over a dozen asylum cases, offering profiles of Central American countries and the systems present within their borders.

In connection to the International Day of Peace this year, we wanted to learn more about Rob and his path to teaching at Goshen College.

Q: Let’s start with how do you define peace?

A: That’s a hard question. I think peace is a community of people who relate positively to each other, are able to meet their own needs and help others.

Peace is not a quiet prison. It’s positive, it’s relational. It’s people in community practicing honesty and transparency.

Q: The theme for the International Day of Peace this year was “End Racism. Build Peace.” Can you speak to how your work has encountered this theme?

A: Well, it’s no secret that our society practices mass incarceration but also racialized mass incarceration, impacting people of color at a significantly higher rate than white people. I don’t think you can talk about building peace without recognizing that fact.

Recently, our society has made some steps towards moving away from mass incarceration, but really prison and probation are the only tools we have in our belt for addressing criminal justice and building peace. And they aren’t very effective. We mark people, essentially, for going to prison which creates barriers to economic opportunities that would break the cycle and truly restore peace.

Restorative justice is a relatively new tool that can help us diversify our options, help us learn about the underlying causes of crime, and violence, and figure out ways to address those and hold people accountable. The goal is to rebuild people by helping them stay with their families and/or support systems and maintain their jobs. An example of what I am talking about can be seen in Vermont, a state where Restorative Justice is woven into the Department of Corrections and also in problem solving courts like the drug court students visited last year in Elkhart for observation as part of the course.

Q: What drew you to criminal justice and restorative justice? Was there sort of an ‘aha’ moment? Is it something you knew you were going to be studying from the start?

A: No. I always sort of considered myself someone who was interested in international peace studies in college. As an undergrad I studied abroad in Guatemala City. After graduation, I went back to live and work as an educator. I intended to study post-war societies, but when I got there, a shift was happening. They were in a period of transition, people’s concerns were more occupied with the growing interpersonal violence instead of overall political violence.

When I went back to grad school I really focused on the systems and cycles that stimulated the growth of gangs. During that time, I started noticing the role of the local churches in these societies, particularly in aiding the exit process for former gang members trying to leave that life behind. It ended up being my dissertation topic and eventually my first book, Homies and Hermanos: God and the Gangs in Central America.

After grad school, I got my first job teaching sociology. I had students of color who were interested in law enforcement in my sociology classes — there was no criminology program at that first position. In order to help, I had to seek out more education on the legal system to help them become better prepared to enter and change the system. That’s when I came across the concept of restorative justice.

Q: What is your goal for the CJRJ program?

A: We all want a community where we know our neighbors and feel safe going out at night. We can continue to choose the threat of punishment to attempt to build that society, or we can find new tools that help diversify our options for public safety.

As a department, we don’t currently have the levers to make overnight changes to the system, but we can give students a new lens, a new perspective on how to address the problems. And that’s the goal of the program. In my class I have future officers and future abolitionists. And we are all discussing the system, sharing our perspectives on how to build better for the future.

Q: So what’s next? What are you working on outside of the CJRJ program?

A: Well, in 2017 I received a Fulbright Fellowship to return to Guatemala for a year and study the rise of private security. It’s an incredibly fast-growing industry globally, but especially in Central America.

Failing power structures are leaving room for the rise of organized crime — mafias, cartels — at the high levels and gangs at the street levels. There is this growing sense of insecurity from citizens.

Then, you have all these unemployed soldiers from demobilized armies, and growing organized crime to employ them — guarding people, guarding property — all these armed people for hire.

I jumped into my position as director of the Criminal Justice and Restorative Justice major at Goshen College pretty quickly after my return. It felt more urgent to get this program going, but eventually, there will be another book based on that experience.

Learn more about the Criminal Justice and Restorative Justice major here.

Learn more about Rob Brenneman and his work here.