The Fashion of Eugene Stutzman ’73

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAKE SMUCKER ’15 of DutchCrafters Amish Furniture

EDITING BY DEBRA GINGERICH of DutchCrafters Amish Furniture

» The Fashion of Eugene Stutzman ’73

» In his own words

» See photos from the Eugene Alexander Fashion Show in Goshen, Sept. 23, 2017

Editor’s Note

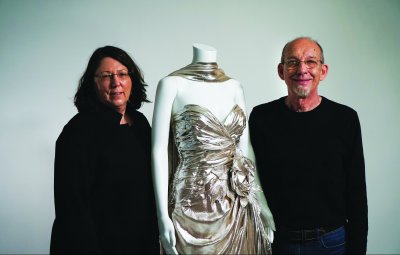

From Sept. 18-24, the local Goshen community held its first “Fashion Week,” with the capstone event being a benefit fashion show featuring Eugene Alexander couture to raise money to renovate the Goshen Theater. And then, an exhibit featuring a selection of dresses from the Eugene Alexander collection was held in Goshen College’s Hershberger Art Gallery from Sept. 24 to Nov. 13, with a reception during Homecoming Weekend. Thankfully, as the designer and co-founder of the fashion line, Eugene Stutzman ’73 was able to return to campus for both of these wonderful events.

His unique story has inspired a number of other Goshen College alumni to get involved. Having known Stutzman from going to Covenant Mennonite Church together in Sarasota, Florida, Susan (Martin) Kauffman ’84 created the Eugene Alexander Hope Foundation and is now its president and collection curator. She has worked tirelessly to find and purchase more than 400 Eugene Alexander dresses after the business had gone bankrupt and there was no inventory remaining. “Here we have a collection of art and it deserves to be preserved,” Kauffman said. “I want it to continue to be generative and bring good.” The foundation uses the dresses to raise funds, through fashion shows, for the social justice causes to which Eugene and Alex were so dedicated.

And it was at one such show a few years ago in Sarasota that Rachel Smucker ’15, then a college student and fashion lover, met Eugene and was inspired by him and his story. She brought her enthusiasm for fashion and Goshen College together by being the event producer for Goshen’s first “Fashion Week.” That event featured a documentary video produced by Jake Smucker ’15 and was underwritten by Jim Miller ’93.

The Fashion of Eugene Stutzman ’73

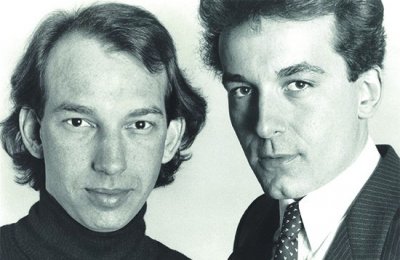

In 1981, Eugene Stutzman ’73 and his husband, Alexander Wallace, put their first names together and created what became an iconic 1980s fashion label. Nearly broke, Alex went to New York City with 10 ornamented dinner jackets Eugene had handmade and a list of Seventh Avenue reps who might carry the new label. After many rejections, agent Rod Owens agreed to take the line on a trial basis. Alex surreptitiously draped the Waterlily Jacket on a display that looked out on the elevator lobby. And in a classic serendipitous occurrence, the buyer for Saks Fifth Avenue saw the jacket as the elevator doors opened. It was not her intended floor, but she got off the elevator and told a flabbergasted Rod Owens she wanted this jacket for all her stores, a holiday catalog, a New York Times ad and Rockefeller Square windows.

Eugene expected to have small orders from small boutiques. A huge department store order of $50,000 came as a shock. Eugene was able to secure a loan with his father’s co-signature. Eugene recalls, “Being a good Mennonite, it didn’t occur to me to entrust the making of these beautiful jackets to a garment factory. We do our own work. Alex and I rented a workshop, hired about eight women and started to make the Saks order. We had three months!”

That first season, Eugene Alexander jackets were purchased by nearly every major department store in the country, including Neiman-Marcus, Bloomingdales, Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord and Taylor, Marshall Field’s, Garfinckle’s, Lazarus, Filene’s and Nordstrom.

They expanded the line to include ball gowns and within two years, became a major resource in the special occasion market. Costumers from Hollywood trekked to the Eugene Alexander showroom at 498 Seventh Avenue in New York. Eugene Alexander’s cinematic style perfectly suited iconic 80s shows such as Dynasty, Dallas and Knots Landing. The line was also selected to represent fragrance launches, most notably, Elizabeth Taylor’s Passion. Their Sarasota, Florida workshop was 12,000 square feet and employed 30.

By the early 1990s, competitors started knocking-off the Eugene Alexander look with cheap, off-shore labor. The regional department stores, Eugene Alexander’s best customers, were merging or going out of business. Eugene recalls, “The fun went out of the business. Computers replaced the smart buyers, stores demanded huge discounts, sales floors were staffed by inexperienced, minimum-wage clerks.” Eugene Alexander had been one of the first high-end evening wear lines to earn the coveted “Crafted with pride in the USA” label. By 1993, Eugene Alexander was one of the last remaining manufacturers who carried this label.

The difference between fashion and *iconic* fashion is the story behind the clothes.Special thanks to our Story Sponsor DutchCrafters Amish Furniture for telling the story of Eugene Alexander! Here's a sneak preview of a short video we're going to share during the Eugene Alexander Couture Runway Show! ✨

Posted by Eugene Alexander on Monday, September 18, 2017

Eugene Alexander closed its doors in 1993. Eugene and Alex continued to work in design-related activities and the collection of antiques. When Alex passed away in 2005, he and Eugene had enjoyed 30 years together as soul mates and artistic collaborators.

A great tribute to the enduring quality of their work is the fact that many dresses still exist. Online auctions regularly sell Eugene Alexander gowns for more than their original retail prices. The gowns that helped to define the Epoch of the Woman live on to inspire and remind us of where we have been.

In His Own Words

In His Own Words

“Mennonite fashion designer” is a distinction I embrace with pride, gratitude and a good dose of Anabaptist humility. The fashion designer’s job is to observe and reflect on the culture and the social, political and economic forces that are transforming that culture. These observations are viewed through a lens colored by the designer’s life journey. For me, this lens was in large part created by my time at Goshen College where the Anabaptist vision of serving in community and championing social justice was the cornerstone of an excellent liberal arts education.

Most of my work in fashion occurred during the 1980s, a time of great social change. As a gay Mennonite, my personal life lens was greatly affected by this social change. My partner, Alex, and I were happily accepted into the fashion industry but unhappily rejected by many factions of society, including the Mennonite Church. This acceptance and rejection made us empathize with the women’s movement and appreciate the impact fashion could have on that movement.

Special occasion dressing, the category in which most of my work fits, offered women the opportunity to make bold personal statements. Daytime business attire for women emulated boardroom menswear. Power suits with aggressive shoulder pads were de rigueur. But for special occasions (still described by the male moniker “Black Tie”), many women wanted more feminine attire while still presenting a strong, accomplished image. This was the niche into which my design aesthetic fit perfectly.

As a gender non-conforming child, my mother, wise beyond her era, patiently taught me to sew and encouraged my often eccentric and theatrical creations. Much of my fashion work was inspired by experimentation with three-dimensional fabric manipulation. My invention of pleating devices and other sewing jigs and techniques created the Eugene Alexander look. Large, three-dimensional flowers were a signature ornamental motif used throughout our collections spanning 14 years.

In viewing this exhibit, I also see the influence of the simple, often naive color combinations of Amish clothing and quilts I observed while growing up in Holmes County, Ohio. Startling colors paired with black show up season after season.

I was often asked where my line was manufactured. Unlike most of my competitors, I could proudly say that it was made entirely in my own factory in Sarasota, Florida, by fairly paid, satisfied workers. The Anabaptist lens through which I viewed my design career did not permit the unjust exploitation of labor. Thank you, Goshen College, for instilling in me and my generation of students the social justice sensibility that still informs our lives.