Unexpected grace and gratitude in prison

This article appeared in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of The Bulletin. It was first published on grateful.org, and is republished with permission from Grateful Living.

By Brooke Rothshank ’00

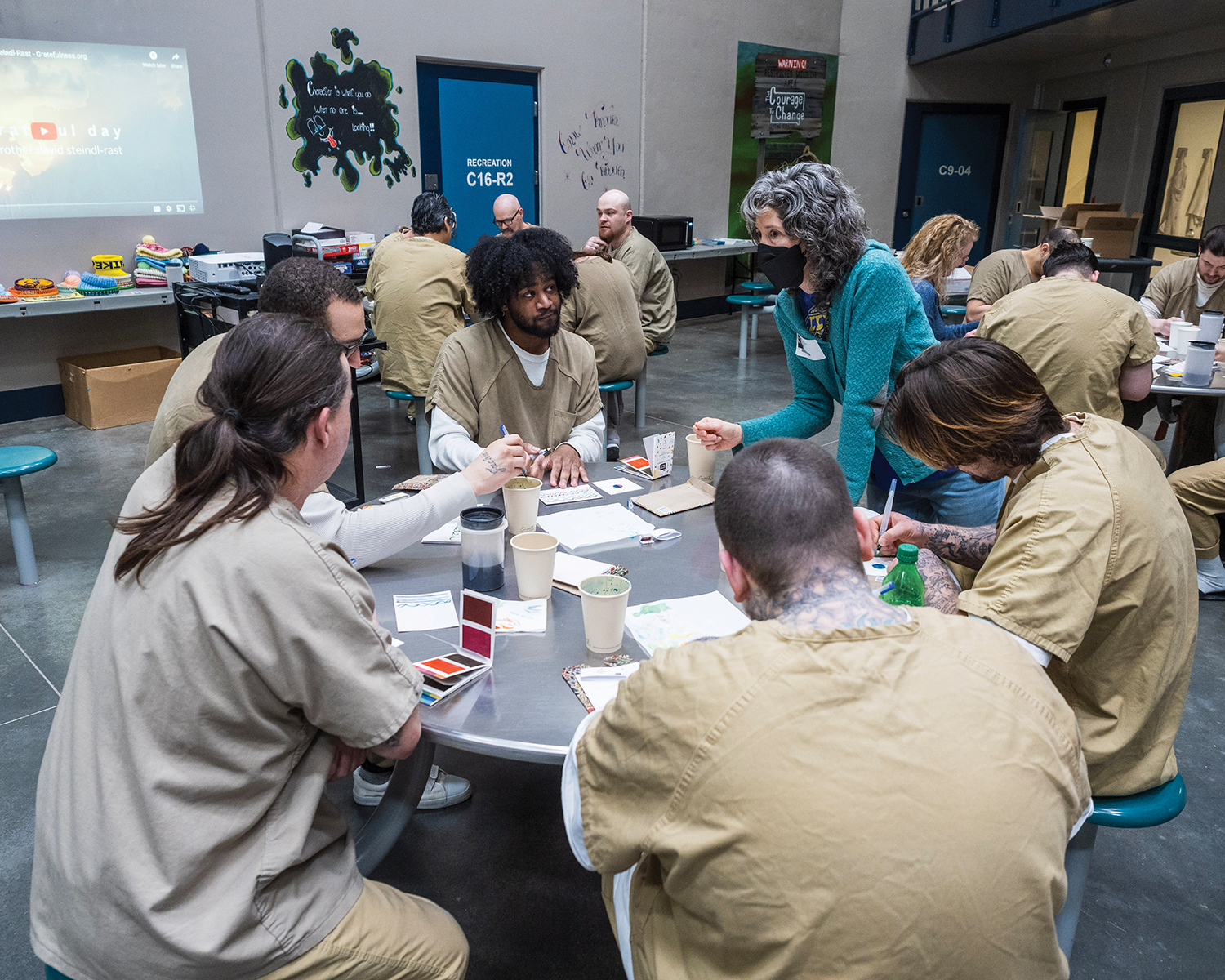

Photos by Cory Martin, chaplain of the Jail Ministry of Elkhart County

I’d been preparing for weeks — technically years, if you count my art training and gratitude learning — but the last few weeks had required a deeper dive into thinking about discussing gratitude with people experiencing hard things. I was preparing to teach a five-session course on painting miniatures with an emphasis on gratitude at the Elkhart County Jail in Indiana. Together, the inmates and I would explore watercolor techniques to create paintings that represented one thing we often take for granted: our senses. The plan was to have each participant paint a miniature image based on one of the five senses each week and to consider how gratefulness awakens our appreciation towards life.

My excitement for being able to teach again after a two year break due to the pandemic was soon tempered by feelings of imposter syndrome.I questioned how I would be able to encourage gratefulness from my perspective as a privileged, cis gender white woman to men of varying cultural identities facing challenges so different from my own. I worried I’d end up rambling in the way I do when I’m nervous, or that we wouldn’t be able to relate to one another. I told myself that my lone actions were not going to solve any problems or make a difference.

As these thoughts swirled, an Instagram post I had read by the brilliant Shannan Martin, who happens to be married to Cory, the jail chaplain, kept coming back to me. In it she said, “As the whole world rattles with anxiety, a small portion of peace could be found if we’d pour our actual selves into unspectacular vessels, and decide it’s good enough to share.”

This permission to let go of overthinking how I should — or could — be different felt powerful and invited a deep exhale of relief. I wondered, if my actual self gets it wrong, can I be open to the tenderness of being taught?

On the morning of the first class, I met Kris, the program coordinator; Holly, the effervescent tattoo removal technician; and Cory, the jail chaplain with a Santa beard. We spoke briefly then walked back down the enormous hall together. When we arrived, the men were already there, about 30 in total, finding seats at round tables. I began to talk and could see the group was attentive and responsive, encouraging even.

We started with a small painting exercise to become familiar with the supplies. Each person was to imagine someone who had been kind to them while they filled in a circle with color and pattern. The men dove into their work and seemed delighted with the vibrant paints. Each painting was unique.

We talked about blending colors and the qualities of the paints. We discussed how when we are young there is a freedom in our creativity that often gets lost as we age. There was agreement that we tend to be unkind to ourselves when we try something new. It’s easy to expect it should be a certain way that we have been told is “good,” instead of being curious about what unfolds from our efforts.

We watched a brief video called A Grateful Day. I could see appreciative nods and smiles as common daily experiences we often forget to appreciate flashed on the screen. We closed our eyes to think about sight and how different our days would be without it. Everyone completed a one-inch painting of an eye. While the men painted I talked about gratefulness strategies and handed out their gratitude journals. Expressions of delight rippled through the room as hands explored the textured covers and smooth blank paper. I wondered what might fill those pages. I don’t think I’ve ever taught a more engaged group.

The class ended with fist bumps and handshakes. Many helped with cleaning up and thanked me for coming. One man showed me his colored pencil drawings. Another told me about his daughter who was born the day before. One told me about his beloved parrot who died while he was away.

As it turned out, I didn’t need to be so worried about meeting these men. They each reminded me of the men in my life — cousins, brothers, uncles, neighbors. Some were quiet and soft spoken but clearly paying attention to everything. Others had quick wit and a lively sense of humor. Many were hard working, wasting no time getting started and staying on task beyond the time to clean up. Some left me wondering how they really felt while others were hungry to talk and share their ideas and hopes.

When I left that first day I felt as if I had discovered a room full of goodness that was hidden away. I know these men made mistakes. I know I’ve made mistakes. We didn’t know each other’s past, so all we could do was start right there in the present. We were coming from different experiences, but we had a reason to be together and that was enough to find some common ground. The willingness of these people to receive my teachings with so much appreciation was surprisingly emotional.

I had been so concerned about what I would teach and share that I forgot to prepare for what I would receive. I thought about how easily I could have missed the chance to meet these people. There were enough reasons and plenty of uncomfortable feelings that would have made it simpler to not go.

Class definition ofthe word “stranger.” The opportunity to meet incarcerated people working toward es are finished now. I think about this group of men and how they have helped to shift mychange inspires me to work toward change.

I don’t know exactly what comes next, but I do know that I don’t ever want to miss the unexpected grace in the face of someone I have not yet met.

Brooke Rothshank ’00 is an artist in Goshen. She works primarily in miniature watercolor, and has illustrated several children’s books. View her work on her Instagram page @blrothshank. This article was first published on grateful.org, and is republished with permission from Grateful Living.