Field Trip to Matagalpa and Esteli: Saturday, June 1

Saturday was an emotionally intense day that saw tears as well as incredible inspiration. Our textbook on Nicaragua begins the history section with this quote:

The history of Nicaragua is among the most turbulent and interesting in all of the Americas. If, on the one hand, it features incredible elite exploitation, mass suffering, and foreign interference, it also includes a significant element of popular resistance, national pride, and human nobility.

Today we heard and saw each of those features, the bad and the good, first-hand. As Alejandro later wrote in his journal, this day “was an emotional roller-coaster for the students and for the SST leaders.”

On our way out of Matagalpa we stopped at the cemetery to visit the tomb of Ben Linder, a young engineer from the U.S. who volunteered in the 1980s to build small hydroelectric projects for remote rural towns without electricity. The U.S.-backed Contra guerrillas were active in this area and frequently targeted those doing development work, regardless of whether they were Nicaraguan or foreign. Ben was one of their victims. An autopsy and interviews with Contras after the war revealed that while working on the project he had been ambushed with grenades and then executed while wounded. In addition to his engineering skills, he was a unicyclist and clown, skills he had also used to help in local vaccination campaigns for children. On his tomb is a unicycle and the word “Internacionalista,” which roughly translates as “Global Citizen,” an accurate description of his dedication to use his education to serve regardless of national borders. In the two towns where his hydroelectric plants brought electricity, his contribution is appreciated by all.

After a 2-hour drive we arrived in Esteli, another major city nestled in the mountains. This area saw heavy fighting in the insurrection to overthrow Somoza, and the surrounding mountains were frequent sites of Contra attacks in the ‘80s. At the Museum of Mothers of Heroes and Martyrs we listened to Germina Mesa tell the story of losing her son in the war after he had to flee for his life at age 14 and went to join Sandinista guerrillas in the mountains, where he was caught by Somoza’s army and decapitated. It was hard for us to listen to the many details, but we discovered it was emotionally more painful for her to tell the story of her son’s death. When she exhorted the students that war is horrible, students later commented that the message was clear in a way they hadn’t understood before. Staring at us from the walls were rows and rows of photos of those who died, most of them the age of the students or younger.

As mentioned above, today we got an insight into mass suffering, but we also saw human nobility. Germina told how her sister, because she supported the Somoza dictatorship, had previously shunned Germina and mistreated Germina’s daughters to the point they almost died; however, when her sister later became terminally ill, Germina spent month after month selflessly caring for her sister until she succumbed.

After lunch we drove out of the Esteli valley, up over a gorgeous mountain range, and 2 hours later arrived at El Lagartillo, a small community of only a couple dozen houses where we divided up and became guests in different homes. Again, as our textbook had summarized Nicaraguan history, here we heard stories of suffering and intervention, but we also saw resistance, pride, and more.

The community was born as a farming cooperative in 1984, but at 8 a.m. on Dec. 31 that same year a group of 100-150 Contras attacked from three sides. Some of those who survived the attack walked us through the village showing the school that the Contras had burned and where two 14-year-old boys were killed while fighting to defend the school. Twelve other community members had been armed in case of an attack and fought for two hours, until the Contras left. We came to a memorial the community had built to honor the two boys and four other community members who died. A mother, Florentina, showed us the marks on a tree where her daughter, an artist who had been crippled with polio, had been fighting when a grenade killed her. Florentina’s husband was also killed. Many of the women and children were able to flee through brush and brambles behind the cooperative to escape over the mountain to a neighboring town. Now, every Dec. 31, so the children will remember their community’s history, together they walk that path to reenact the exodus they call “The Inferno.”

The community struggled during the rest of the 1980’s. The number of Contra attacks increased as the Contras got more aid and weapons from the U.S. government and from an arms-for-hostages exchange that became known as the Iran-Contra scandal. Human rights organizations documented frequent Contra attacks on cooperative communities like Lagartillo as part of a broad strategy to hurt Nicaragua. Although Lagartillo was not attacked again, residents said the Contras remained active in the area, sometimes torturing and executing neighbors whose horribly-mutilated bodies were left as warnings.

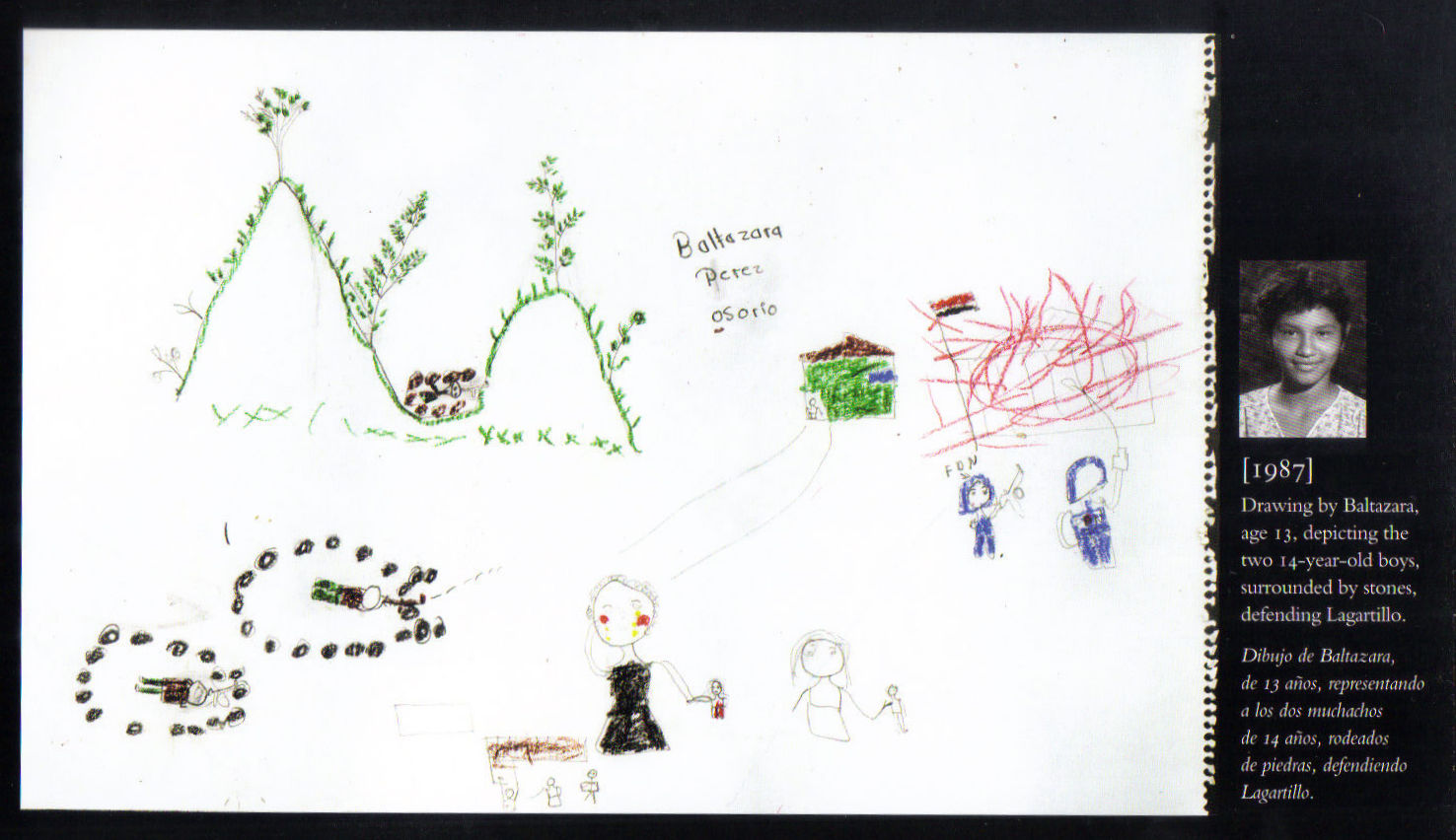

At 6:00 the students returned to their temporary homes for supper with a local family. Doug, his son Josh, and Yuriy stayed in the home of Balta and her son Jose. Doug recognized Balta from a book on victims of the Contra War then and now (Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy of U.S. Policy), which features a drawing she made at age 13 of the attack, showing Contras in blue uniforms burning down her school, women crying and fleeing with their children, and her two 14-year-old schoolmates fighting from inside stone circles. In the late 1980’s drawings by Balta and 24 other Nicaraguan children were posted in subway trains in the Washington D.C. to alert the U.S. public to what its country was doing in Nicaragua.

After supper we got a glimpse of the spirit and determination the community has channeled in other directions after the war. In contrast with the malnourished children we saw yesterday, the Lagartillo kids we saw are well-fed not only with food but with culture. Earlier we had seen the community had its own small library building and a secondary school, neither of which are usually seen even in communities several times larger than Lagartillo. The community has also done well enough that it built a Cultural Center, where that evening a children’s theater group put on a play about protecting the environment. That was followed by a concert from an acoustic band, which had just arrived from giving a concert several hours away, singing their own compositions (to the accompaniment of a guitar, a violin, a mandolin, and bongos) that were brimming with Nicaraguan pride.

After thoroughly impressing us and blowing our socks off, the community asked if would play them in volleyball. Still smarting from the licking we took in soccer by the kids in Awas, we decided to try our luck in volleyball. Two bright lights were set up outside, lime was poured to make boundaries (that’s when we realized they were serious), and we contributed our own patented “digital scoreboard” to the competition. The first game went to El Lagartillo. They switched players for the second game …. and beat us again. The third game we won! With Goshen in the groove our self-confidence surged into the fourth game, we soon stood expectantly at match point — before the community rallied and came from behind to beat us again. In multiple ways, El Lagartillo is one persistent community.