Migration

Over the past 30 years, Lima’s population has grown dramatically. Millions of refugees fled here to escape the ravages of war between Shining Path terrorists and the Peruvian military in the 1980s and early 90s. In recent decades, even more families have relocated here in search of higher incomes, better schools and broader opportunities. This influx of people from the mountains and rain forests makes Lima a vibrant, dynamic city. At the same time, local authorities struggle to mitigate the impacts of unplanned development on the edge of the city — congestion, traffic, smog, noise, crime and lack of basic public services, including roads, parks, running water, sewer and electricity.

We traveled south to a thirty-year old settlement named Villa Maria del Triunfo to hear the story of a particular family, the Taipes, and experience life in their neighborhood first hand. The family’s matriarch, Alicia, welcomed us to her home and described what it was like to be part of the “invasion” of this area in the early 1980s. Alicia recounted how she and her husband constructed their first home with reed mats and poles propped up on the desert sand. She remembered the bomb placed nearby by Shining Path terrorists several years later, starting a fire that destroyed the houses in her neighborhood. She recalled the economic shock instituted by President Fujimori in 1990 and the huge pots of soup she prepared to try to feed her family and friends after the government ended its food subsidies. And she proudly showed the improvements she has made to her home in the last few years, replacing the reed mats and thin boards with concrete bricks and a metal roof.

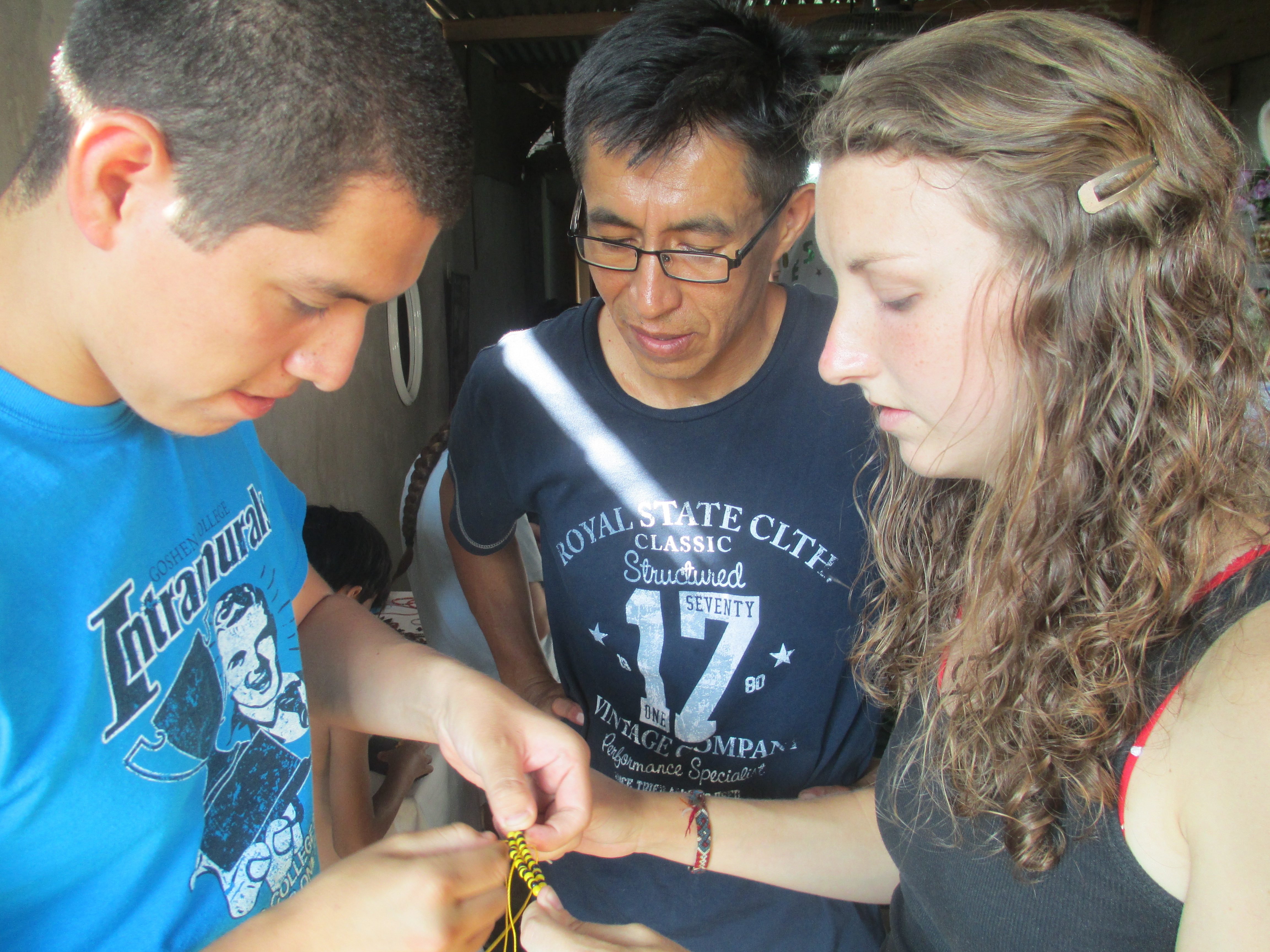

Migrants bring with them their traditional customs and beliefs. Alicia, for example, still uses the herbal remedies handed down from her mother. She demonstrated for us various cures for digestive and respiratory problems, preparing teas made from a dozen types of plants grown in the Andes and sold at the local market. Ricardo and Eliana Mauriola Carrasco, who moved to a neighborhood near here from the Piura area nine years ago, showed how they use beads made from rain forest seeds to produce jewelry to supplement their income. After explaining the origins of the seeds, they gave the students a chance to make their own bracelets and necklaces.

The next morning Martha Taipe, Alicia’s younger sister, took us to her garden to meet Señora Gregoria, coordinator of an innovative urban gardening project that teaches Andean migrants who are accustomed to farming in the rich soils of the highlands how to produce vegetables in the dry, sandy soils of metropolitan Lima. After getting our hands dirty — very dirty — we washed up and enjoyed a delicious meal of anticuchos (skewers), papas a la huancaina (Huancayo potatoes) and maracuyá (passion fruit) juice. Then, suddenly, powder began to fly. February is carnival month in Peru and a traditional way to celebrate is to toss handfuls of baby powder into the faces of friends and family.