The Peasantry

We are reading a book entitled A Path of Our Own: An Andean Village and Tomorrow’s Economy of Values. The author, Adam K. Webb, describes how more than one-third of the earth’s inhabitants live as peasants. Subsistence farmers, they plant crops and tend animals much as their ancestors did. While many in the Global North consider this lifestyle backward or undeveloped, Webb points out that peasant life can have redeeming qualities. The peasantry places a greater emphasis on traditional values such as equity and fairness, life in community, family ties and a basic sense of decency that are becoming increasingly difficult to find in the industrialized world. Peasant communities can be remarkably self-sufficient and independent, with a particular dignity that comes from knowing how to work the land. What would it be like to live in a place where tradition still reigns, where crops are grown without chemicals or petroleum, where one’s community consists of the families living within walking distance, where life is more simple and change comes slowly?

We made a four-day trip to a village called San Juan de Quihuares to see if we could catch a glimpse of the peasantry. Our route took us across a 4,200 meter (13,780 feet) pass with breath-taking views of snow-capped peaks. We stopped along the way for an Andean-style picnic of boiled potatoes, huacartay herb sauce, fresh cheese and corn on the cob. When we arrived in the village we carried our bags a short distance to the San Juan de Quihuares Evangelical Mennonite Church, a small adobe building that provides a place of worship to a dozen families here. The students were paired up and, one by one, host family members appeared at the church to escort the students back to their homes. As the sun set behind the mountains we were amazed at the stars that emerged in the night sky — the Milky Way soon came into view and we marveled at how beautiful the heavens can be when there are no street lights to distract us.

The next day we met at the church for a service project — adobe-making. The sanctuary is constructed of 4,500 adobe bricks, but more are needed to complete the smaller buildings and walls that surround it. We got our hands and feet dirty as we prepared the soil, added water and ichu grass, blended the mixture with our bare feet, and pressed it into forms. After a hard day’s work alongside our Andean hosts we gathered in a semi-circle and counted 230 adobe bricks; they will spend the next few weeks drying in the sun.

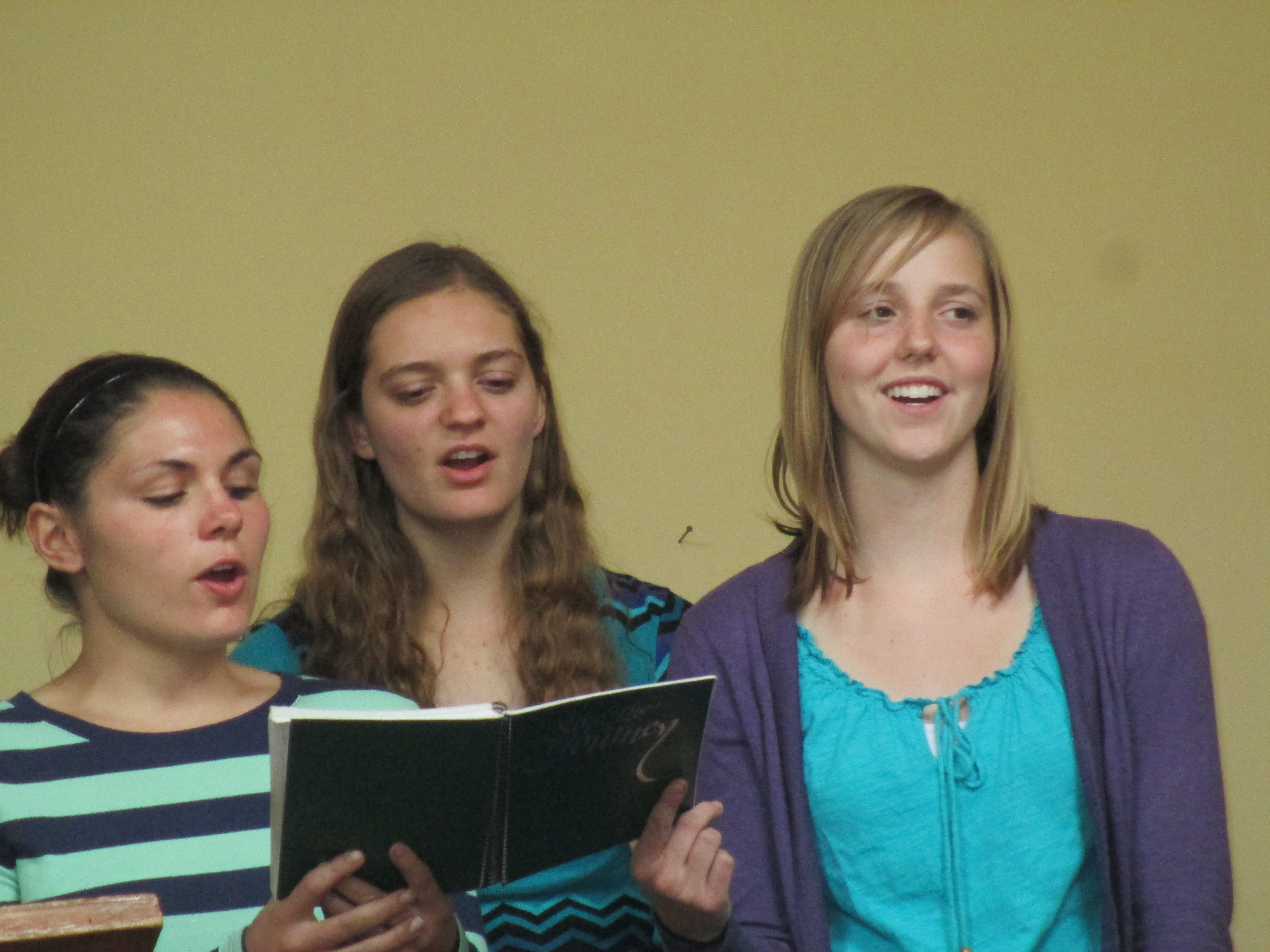

On the following day we joined the families from the church for a time of worship, rest and recreation. The children began arriving early — 7:00 am — for Sunday school. We played games, sang songs and told the story of the Tower of Babel from the book of Genesis. We then gathered together with the rest of the congregation to share praise songs, hymns, prayers, another story and a message delivered in one, two or three languages: our native English, the villagers’ native Quechua, and the language we both consider our “second” one — Spanish — the tongue that brings us together. For lunch we devoured steaming bowls of lamb stew, made from a young sheep that was butchered in our presence the day before. Afterward we climbed the hill to the school playground and enjoyed games of soccer and volleyball.

On our final day in San Juan de Quihuares we gathered at the village’s alternative school. Children from the surrounding countryside spend two-week periods living and studying at the school, then return home for the rest of each month to share what they have learned with their families. The lessons are focused on what young people in this rural community find most relevant — improving their crops, tending their animals, hygiene, nutrition and health as well as the three R’s and other traditional subjects. Prior to our visit we were asked by the school’s director to make a presentation, so the students came prepared with skits on the topic of domestic violence and non-violent conflict resolution.

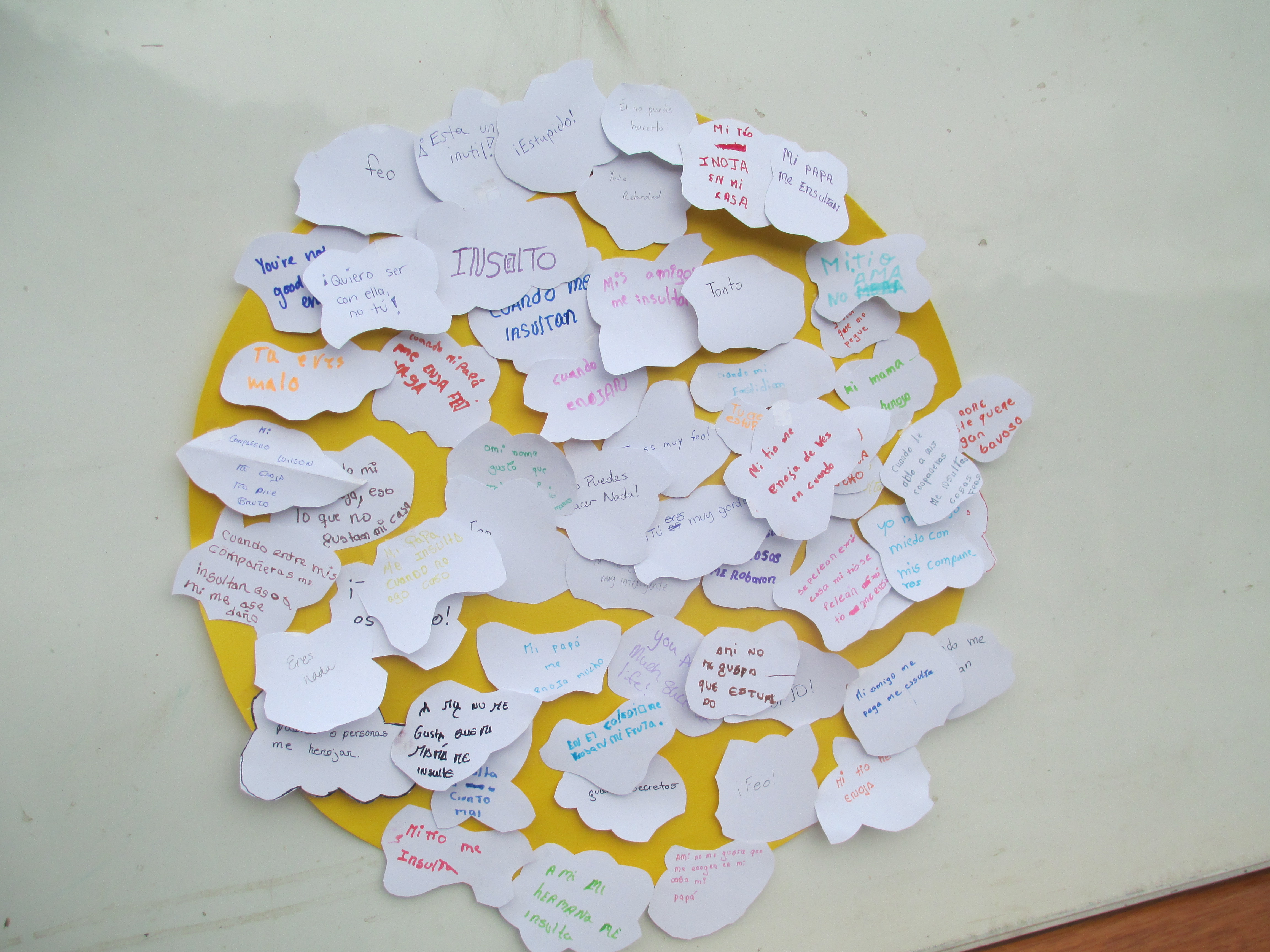

Taking our cue from our workshop presenter the previous week, Cirilo Aguilar from the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations, we ended our presentation by asking the children to write down an insult or discouraging remark that they have recently heard on small pieces of paper shaped like clouds. We taped all the clouds on top of a large yellow sun and noted how they obscured its light. Then we asked the children to write down a complement or encouraging remark on yellow pieces of paper shaped like the sun’s rays. We replaced the clouds (insults) with the rays (complements) and, sure enough, not only did the construction-paper sun take on a different appearance, but the real sun, the one God created, suddenly emerged from behind the clouds and warmed us all.