Playing a game of war to promote peace and understanding

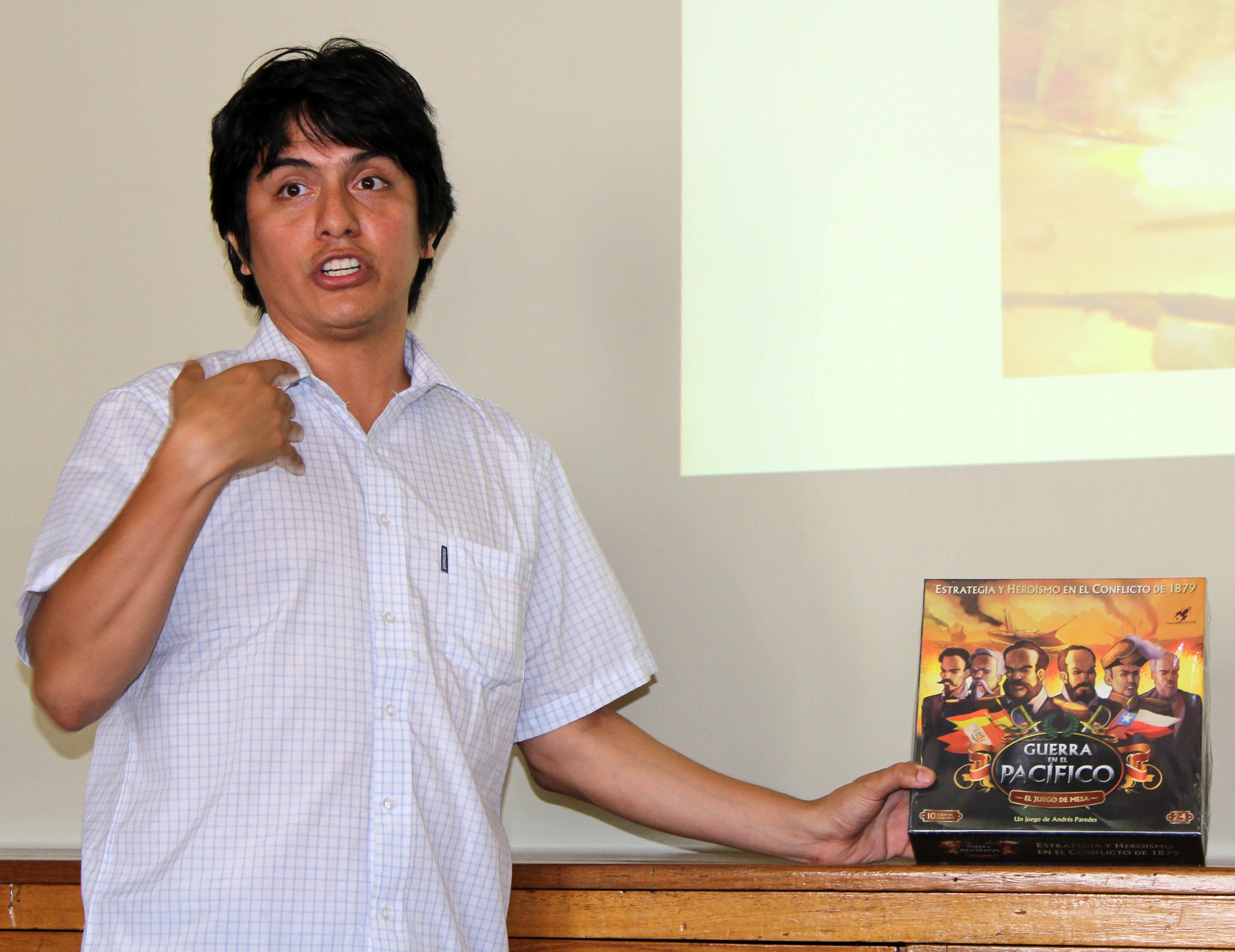

Goshen College students recently got the opportunity to play a war strategy game designed to entertain, educate and foster peace and understanding among the people of Peru, Chile and Bolivia. Andrés Francisco Paredes Salgado, a 35-year-old Peruvian with a passion for writing, history, political science and gaming, invented the complex board game and introduced it to Goshen students.

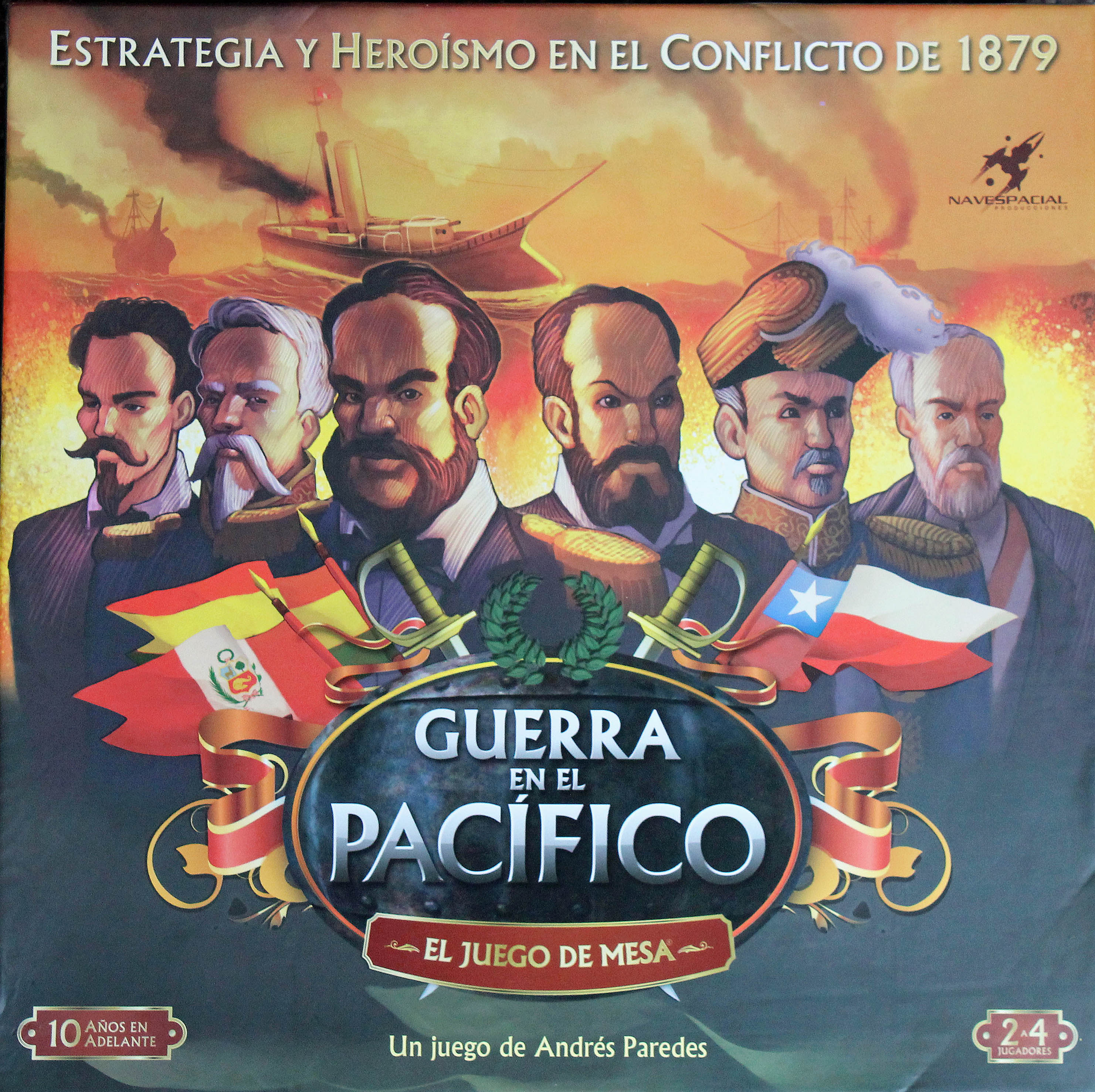

The goal of “Guerra en el Pacifico” (War in the Pacific) is to defeat the enemy, but it’s not the usual board game based on a U.S., European, or make-believe war. It is a game based on the War of the Pacific, the 19th century conflict between Chile, Bolivia and Peru whose outcome continues to spur resentment among citizens of the three nations.

La Guerra del Pacífico (1879-1883) began when Chile invaded Bolivian and Peruvian territory in the Atacama Desert to claim mineral-rich lands. Chile won the war because of its naval superiority and annexed Peruvian and Bolivian territory. Peru still maintained most of its extensive coastline, but Bolivia lost its only port on the Pacific coast, turning it into a landlocked country.

While all of the nations later re-established excellent diplomatic and trade relations, many Bolivians and Peruvians have remained resentful of the war’s outcome: Chile was strengthened economically and militarily while Bolivia and Peru suffered humiliating defeats and lost land – along with some of their national pride.

Animosity boiled over in 2008, when Peru sued Chile before the International Court of Justice at The Hague (the judicial body of the United Nations) seeking the correction of the maritime boundary involving 14,500 square miles (95,000 square kilometers) of the Pacific Ocean rich in fishery resources (anchovy and jack mackerel) and now under Chilean rule. Chile maintained the maritime border with Peru was established in treaties signed in 1952 and 1954, but Peru disputed those claims.

On Jan. 27, the World Court issued what amounted to a split decision: Peru was awarded a larger slice of the Pacific Ocean off its shores, but Chile was allowed to retain fishing grounds with an annual catch estimated at $200 million. Despite that, Peruvian leaders celebrated the outcome, insisting that the court recognized Peru’s argument that no maritime treaty previously existed between the South American neighbors.

Goshen students said many of their host family members were happy about the ruling even as they insisted that they harbored no anger toward Chileans. Still, the surge of Peruvian patriotism was evident everywhere from the placement of Peruvian flags on street poles to news coverage, which emphasized that Peru had finally gotten the better of Chile. And in Chile, people living near the border with Peru marched in protest and politicians denounced the decision.

Nine days after the World Court decision, Andrés Paredes introduced “Guerra en el Pacifico” to Goshen students. In the game, Chile, Bolivia and Peru are at war again, but the outcome can be different based on the skill and daring of the players. Andrés said he developed the strategy game to educate and to entertain, but also to allow players in Bolivia, Chile and Peru to imagine what it would be like to live and fight for another country – to experience a different perspective and to gain a greater degree of understanding of a former enemy. Bolivia, Chile and Peru are interdependent allies, Andrés said, and it’s time to set aside animosity and resentment.

Andrés, who has a degree in Audiovisual Communications from the Catholic University of Peru, is in the process of obtaining a master’s degree in political science. He has delayed his career as a writer, copy editor and post producer for several TV channels to promote his game full time. He has been featured in many Peruvian publications and newspapers in Bolivia and Chile have published stories about the game.

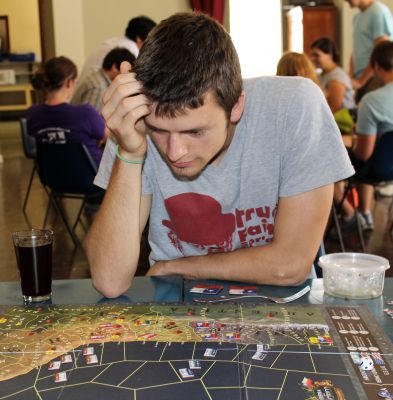

Goshen students said they enjoyed playing “Guerra en el Pacifico” and they embraced Andrés’ underlying messages: it is better to play than go to war and barriers between people (and nations) can be broken down if individuals are willing to set aside past conflicts and live another’s person’s reality.