Dean and Derek: Serving in San Miguel

Goshen College students enrolled in the Peru SST program struggle to adjust to new (host) families, the Spanish language, a new country and a very different culture. Service can be an even bigger adjustment because students leave the comfort of modern Lima and head out to the country, often with just one or two other students and away from the security of a group of Goshen students who have become close and supportive friends. Dean and Derek faced those same adjustments, but moved even further out of their comfort zones by accepting a remote service assignment in a tiny settlement and with people for whom Spanish is a second language.

Dean and Derek are living and working in an indigenous community perched on a hillside far above the Perene River valley. San Miguel de Marankiari is home to several dozen indigenous Asháninka families, who live in the jungle at the edge of the Amazon. Tribal history tells of an elder and his three wives, displaced from their ancestral homeland in the valley below, who founded the community some 60 years ago.

More than 25,000 people still speak the language of the Asháninkas, one of dozens of native nations that originated in the Amazon basin of what is now known as Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia and Bolivia. Many still live far off the beaten path, but the Asháninka people are quickly becoming westernized due to forces beyond their control. Their native language, customs, traditional diet and ways of life are disappearing as members move to cities to pursue an education or make a living.

In San Miguel, electricity, water and sewer systems, and even satellite television have arrived in recent years, bringing comforts but also changing life. Community members are trying to preserve the best of their traditional lifestyle. The founders of Ecomundos, a non-profit organization based in San Miguel, are proud of their Asháninka heritage and are helping the people maintain their distinct identity and customs and stay free of destructive outside influences.

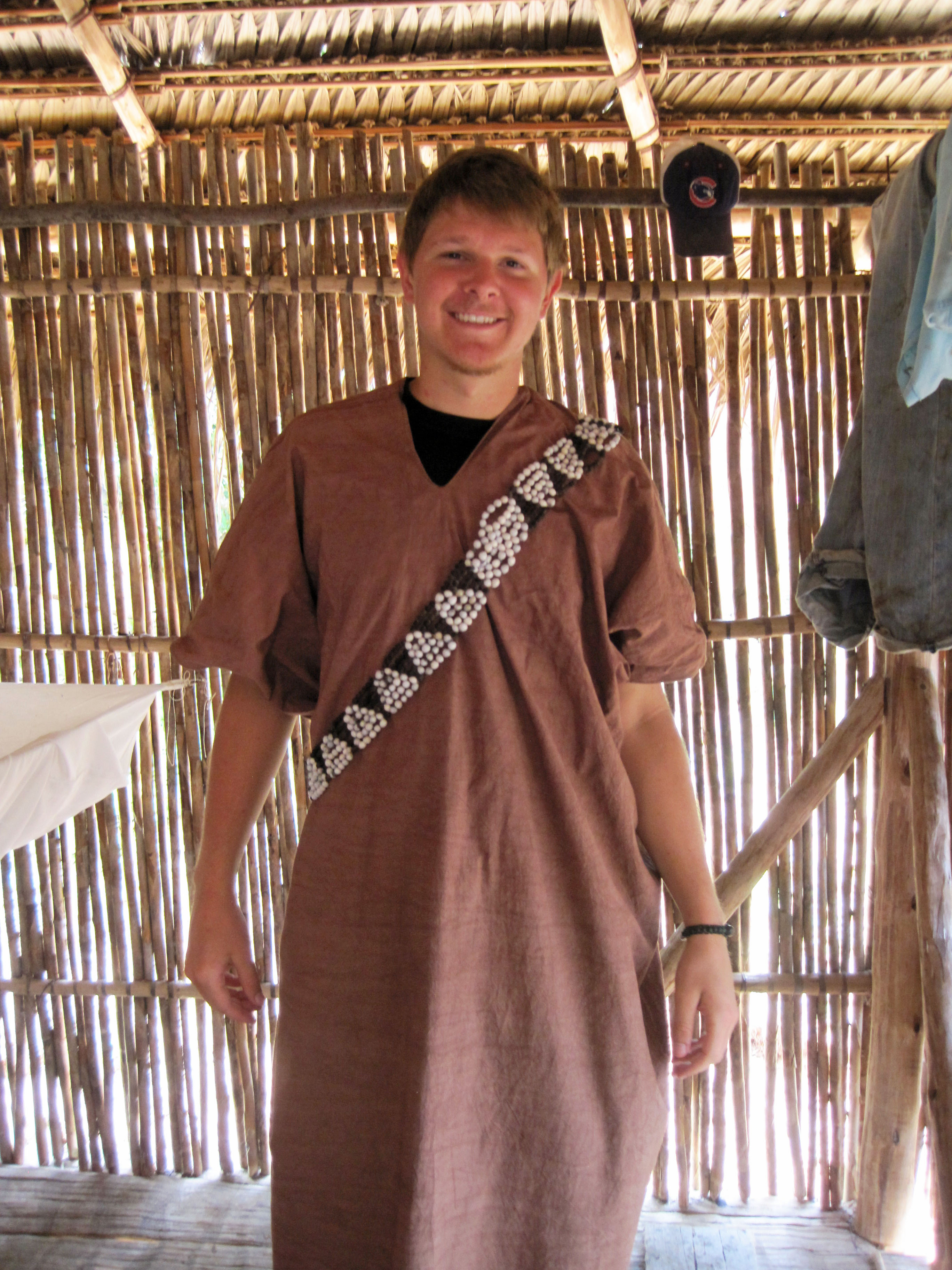

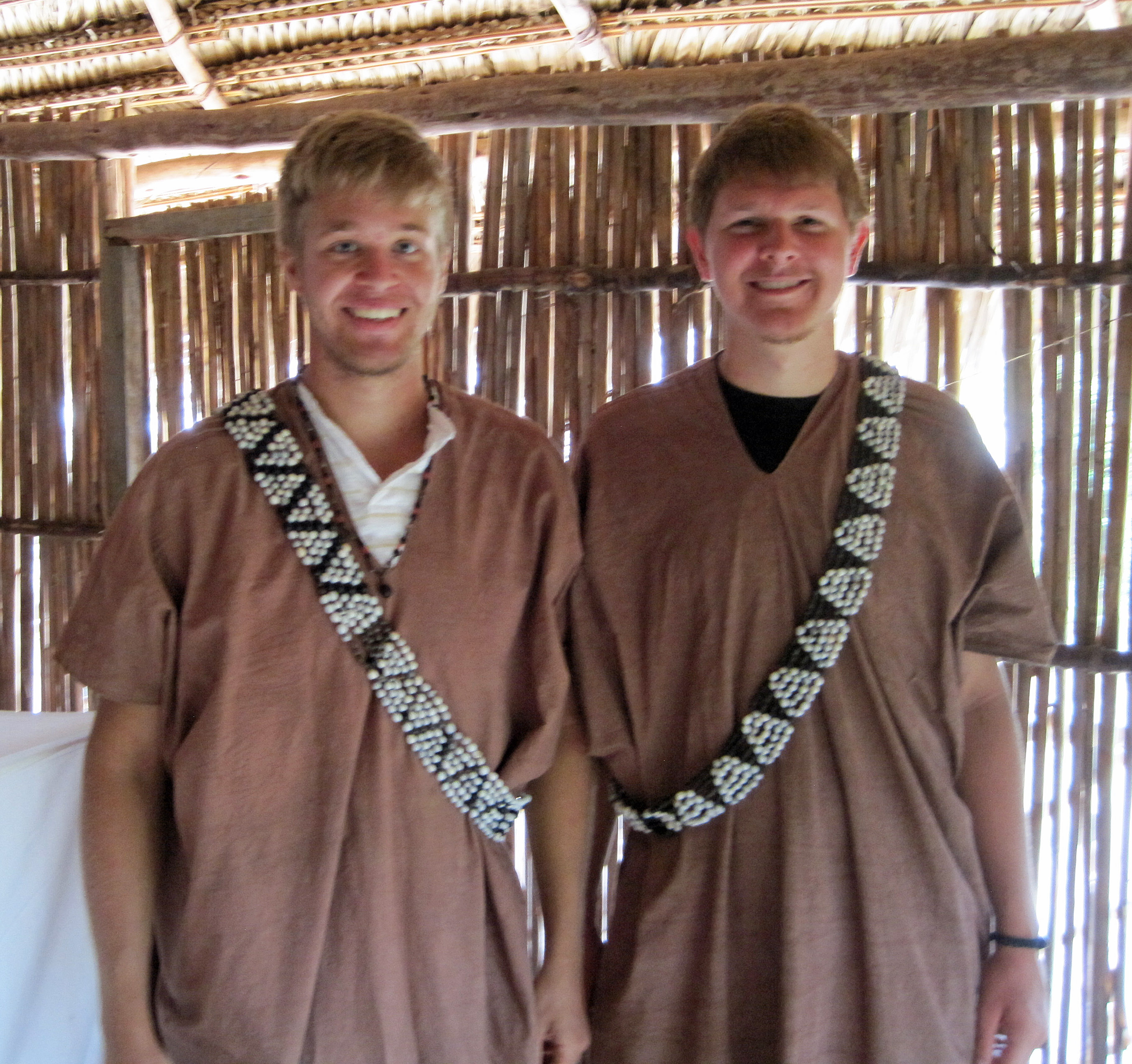

Community leaders hope that cultural tourism, in which a limited number of outsiders (no more than 100 per year) pay to visit and stay overnight in San Miguel in order to experience the unique aspects of Asháninka culture, can provide incomes to families who choose to remain in the village. Many of the residents of San Miguel still live in houses built of carrizo (bamboo), dress in their traditional cushmas, cultivate traditional foods such as yuca and platanos during the day and hunt for game at night, sometimes with a bow and arrow.

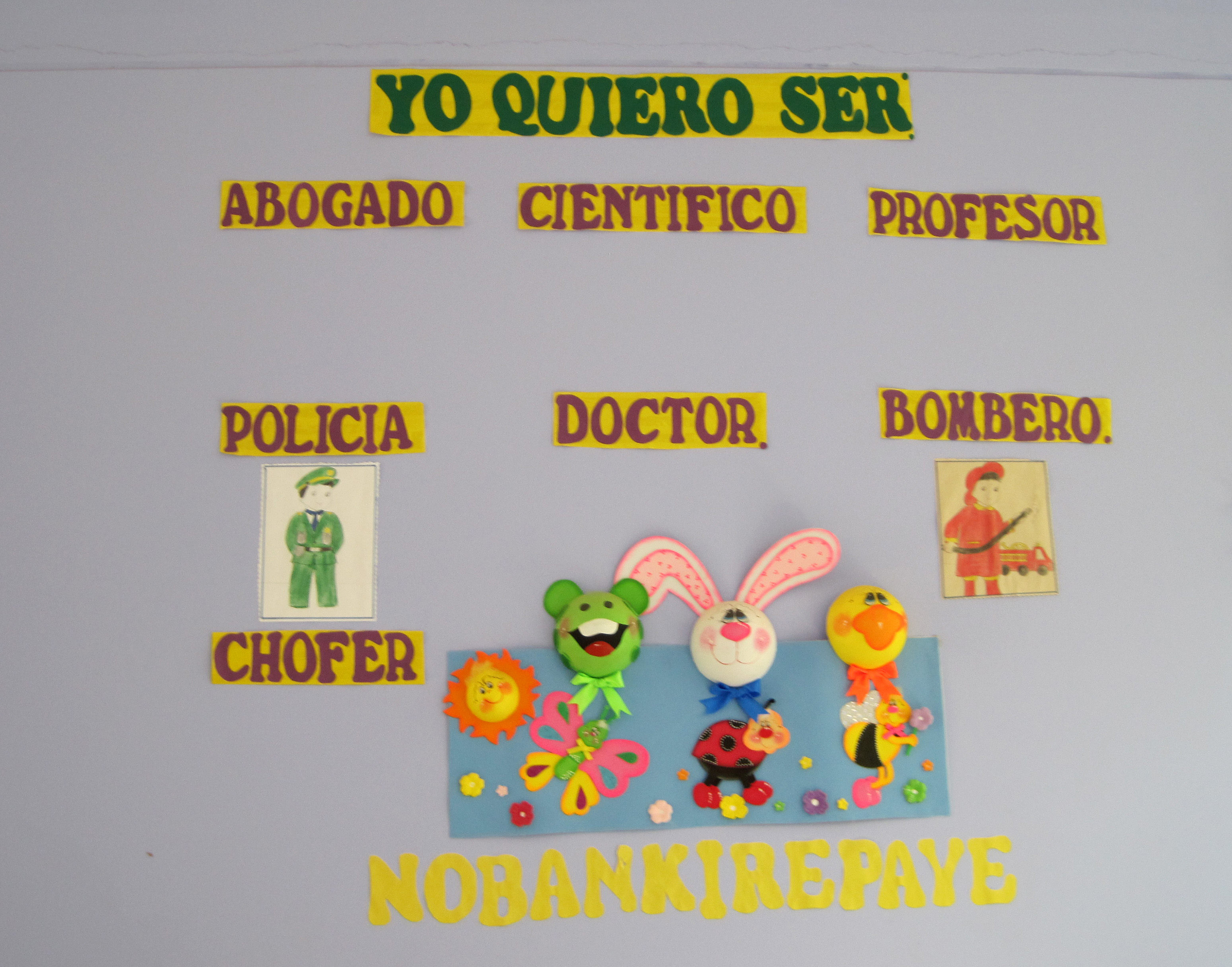

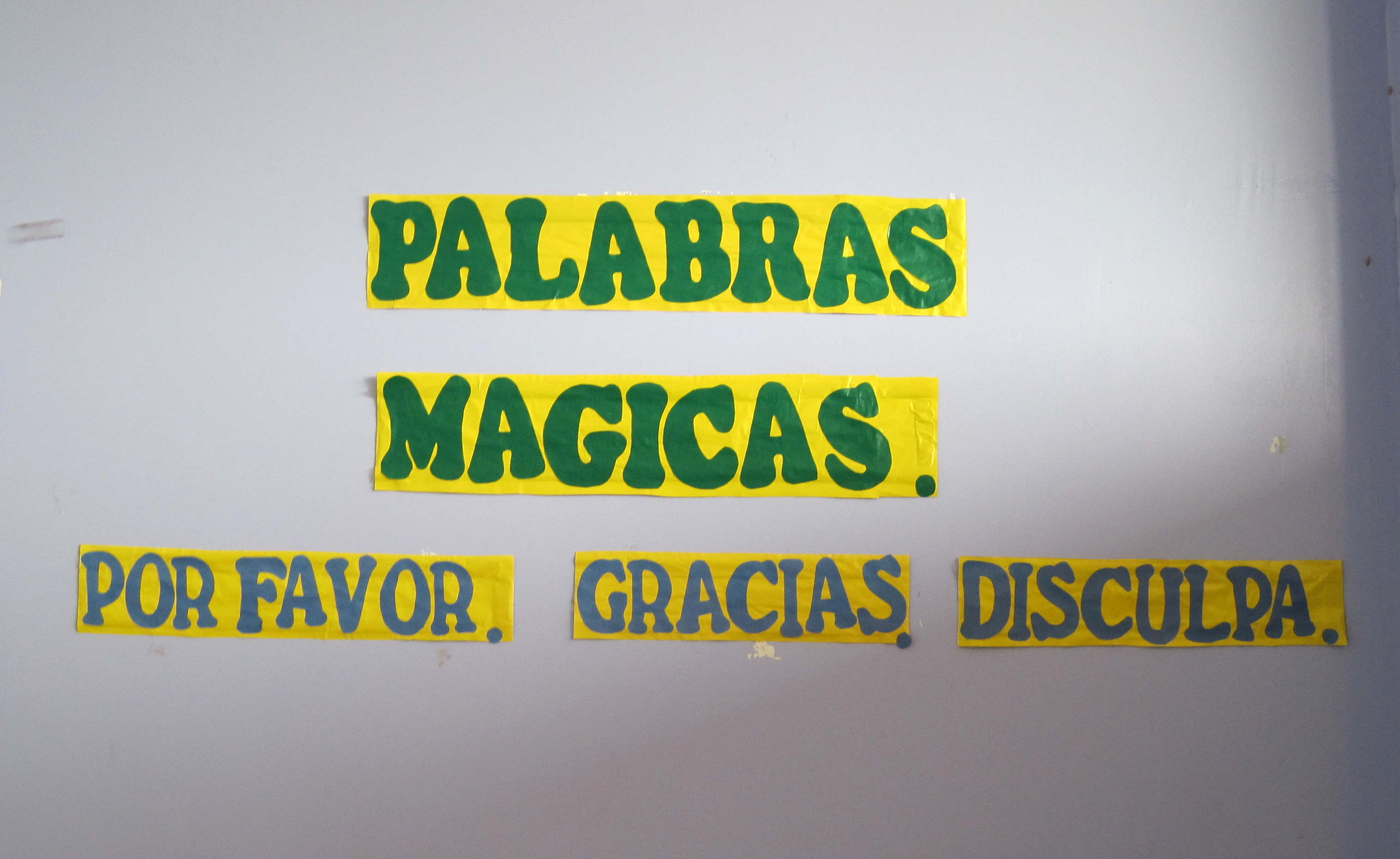

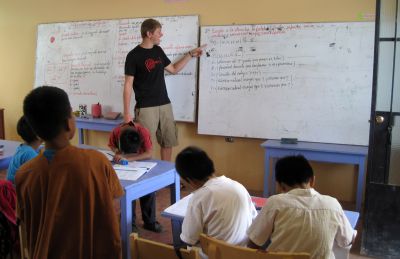

Dean and Derek are participating in the village’s mix of age-old practices like farming and hunting, with more modern activities like watching television. They use the village’s nice, new restrooms (built for visitors), but their host family members still prefer the traditional outhouses. The village has a new, modern school building, where Dean and Derek teach English wearing the traditional cushmas.

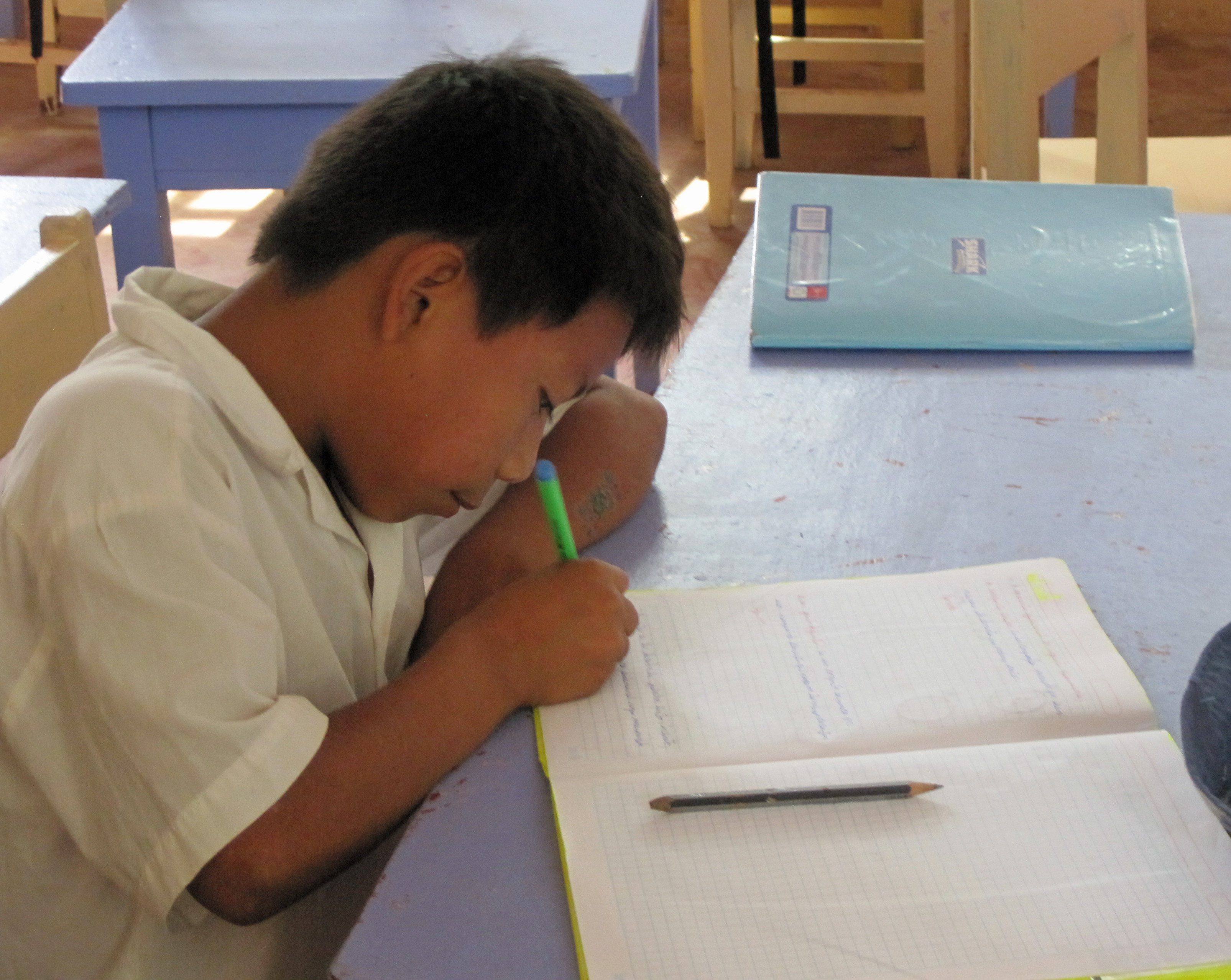

Dean and Derek give the village children an hour on English instruction every morning. In the evenings, Dean and Derek teach English and computer skills to young adults in the community. During the day, the two Goshen students help their host families with farm work. They say they are in great shape from hauling big bags of yucca up the hillside.

Dean and Derek have some great stories to tell from their experience with the Asháninkas, including the time Dean had an armadillo for breakfast. They also killed a snake, hunted for a large rat-like creature with bow and arrow, survived lots of good-natured teasing and celebrated Derek’s birthday with a traditional feast and community gathering, at which he was obligated to make a speech. Their host families appreciate their hard work and willing spirits. The students’ only worry is that their fellow SSTers will be jealous because they are having such a great time.