America’s oldest civilization

Goshen College students spent the afternoon of May 12 exploring the Sacred City of Caral-Supe, which is considered one of the earliest civilizations of the world and the oldest in the Americas. In recent years, radiocarbon dating has confirmed that urban life, complex agriculture and monumental architecture flourished in Caral 5,000 years ago – 2,000 years earlier than anywhere in Mesoamerica or Europe. That puts Caral on par with Mesopotamia, Egypt and China as areas that first gave rise to civilization. Peruvian archeologists call it a cultura madre; a mother culture.

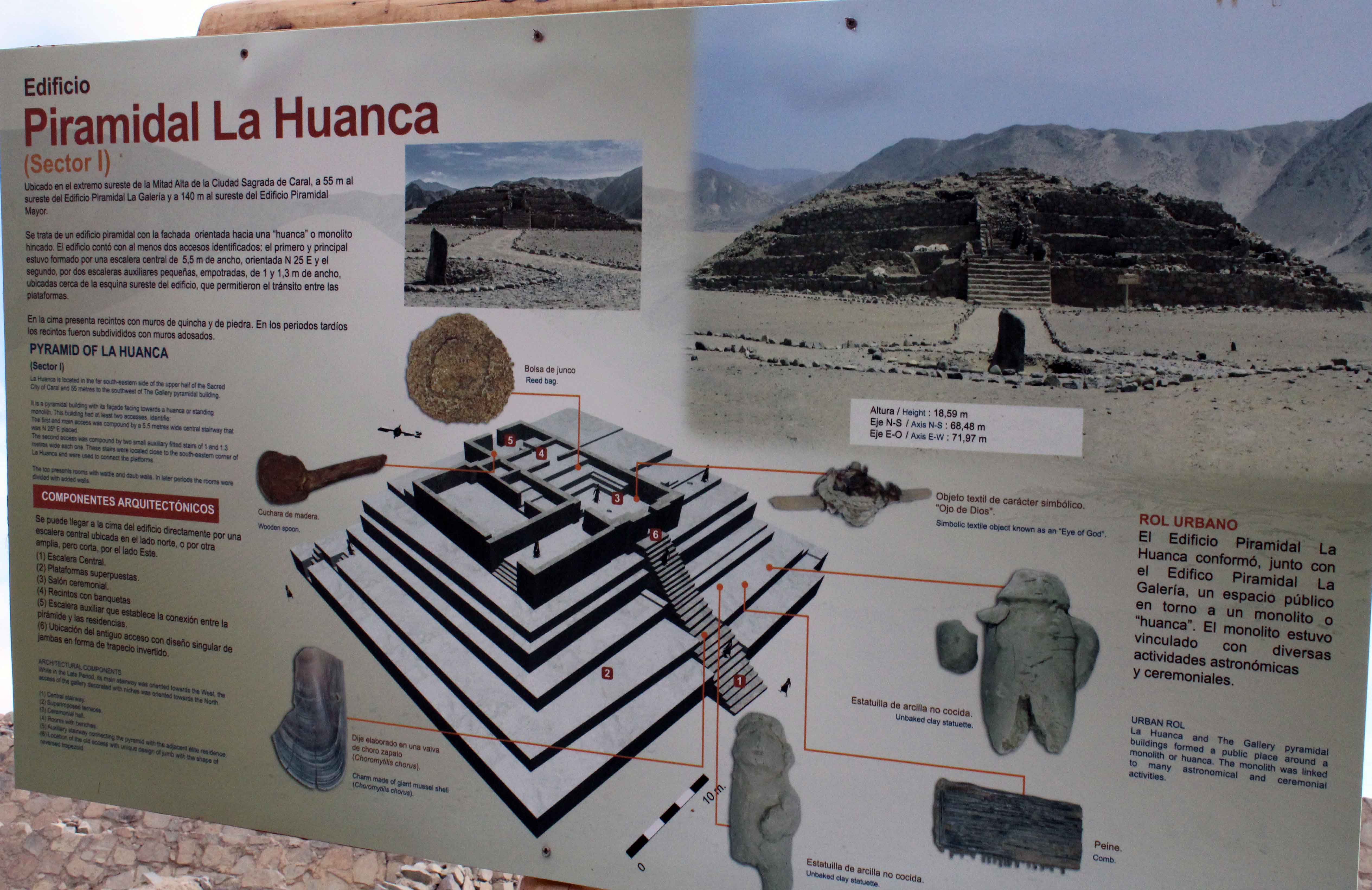

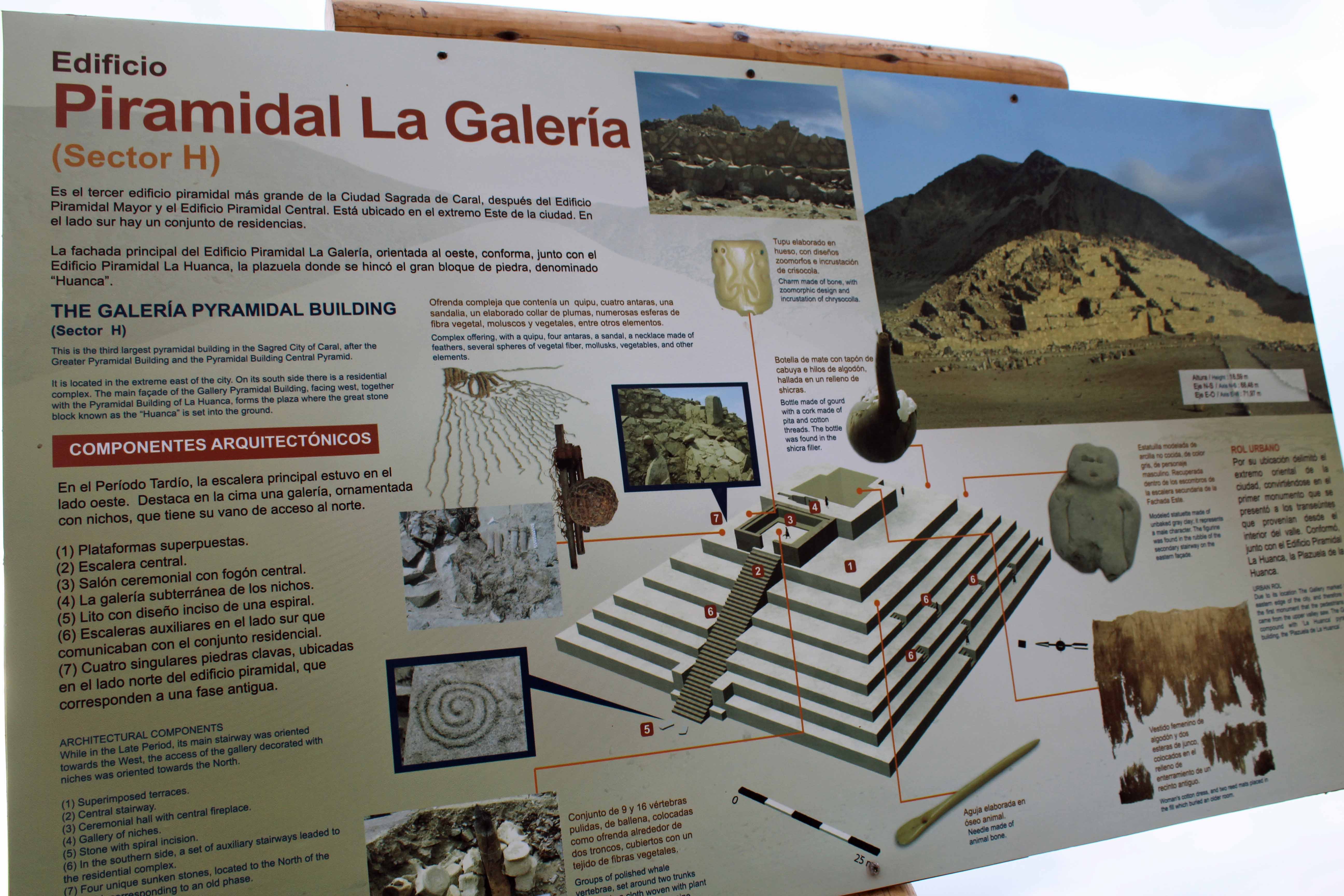

Caral has gained growing international recognition – including being named a World Heritage site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) – for its well-preserved site, which features complex and monumental architecture, including six large pyramidal structures.

However, Caral is relatively little known, even within Peru and well off the tourist trail because of its lack of public accommodations and somewhat remote location. It lies 125 miles north of Lima, on the desert coast, and 14 miles inland from the Pan American Highway. To visit, visitors must endure a 40-minute bus or truck ride over a rough dirt road and then hike nearly a mile to the reception center. Despite its increasing international profile, tours are offered only in Spanish.

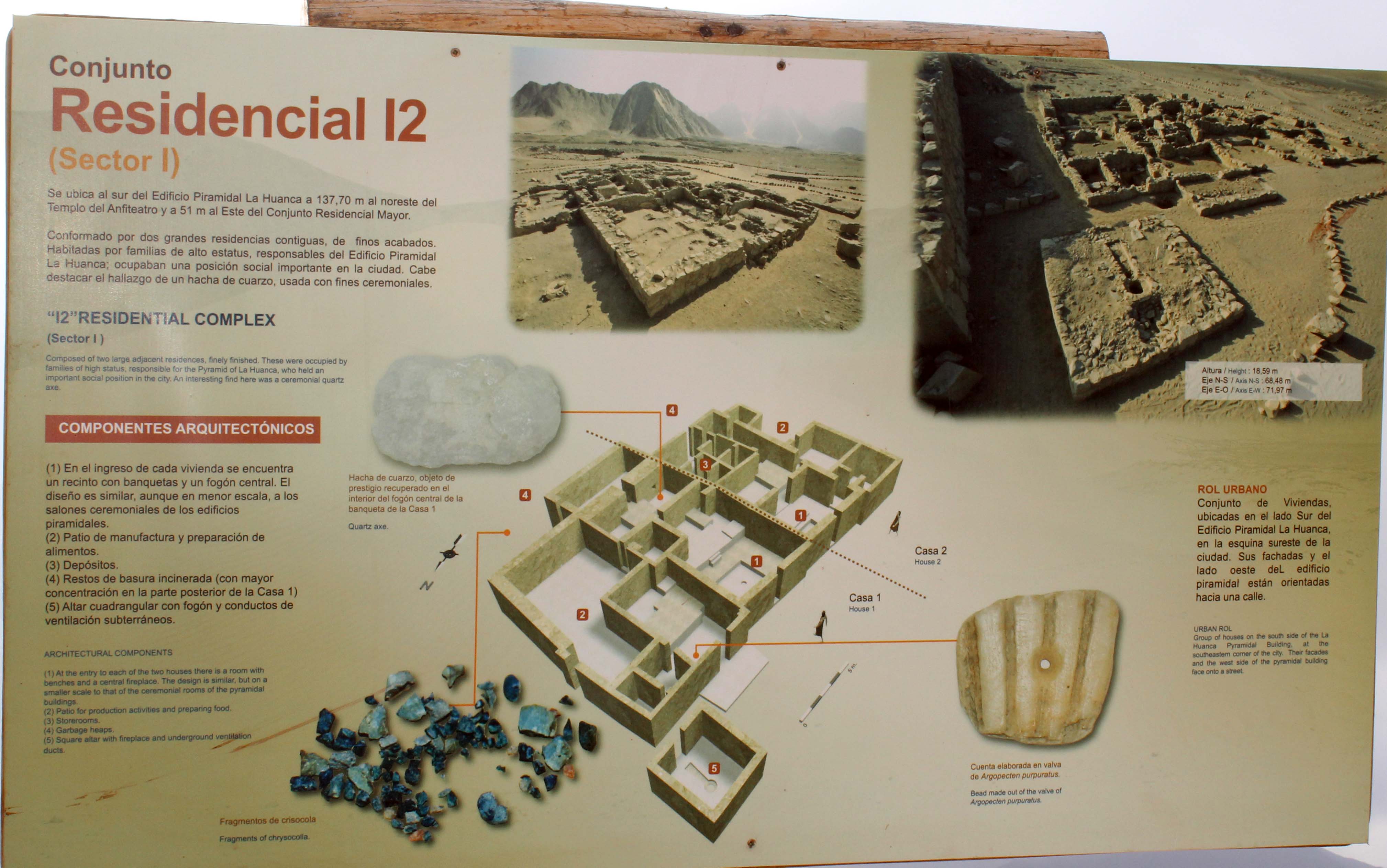

Nevertheless, once arriving, visitors are treated to a stunning sight: 1,547 acres, of great historical and cultural significance, situated on a dry desert terrace overlooking the green agricultural valley of the Supe River. Caral, which was home to about 3,000 people, features stone and earthen platform mounds, sunken circular plazas, pyramids used for religious ceremonies and residential areas.

While the inhabitants of Caral lacked metals and ceramics, they built huge structures, ate a varied diet, developed the use of textiles and built water supply, irrigation and drainage systems. Evidence was found indicating that the people traded widely with inhabitants of the coast, mountains and jungle. Although two cases of human sacrifice were uncovered, scientists have found no evidence that Caral had a military culture or that its people conquered others.

Instead, experts believe the people of Caral were peaceful and spent their time studying the heavens, practicing their religion and playing musical instruments; archaeologists found 37 cornets made of deer and llama bones and 33 flutes made of condor and pelican bones. Among Caral’s important artifacts was a quipu, a record-keeping system involving the use of knots tied in rope, that later was used by other Andean civilizations, including the Inca.

After eating lunch, students hiked to the site and then spent 90 minutes strolling through Caral with a tour guide. There were few other visitors, so the students got to experience the peace and solitude that permeates the site. A number of students remarked that it was amazing to visit a place where civilization thrived at a time the great pyramids in Egypt were just being built.

More than 100 people toil daily at Caral, carefully removing centuries of accumulated soil and restoring stone structures, ensuring that future visitors will be able to see even more and learn the latest discoveries about a mysterious people whose story is still unfolding, layer by layer, rock by rock and year by year.