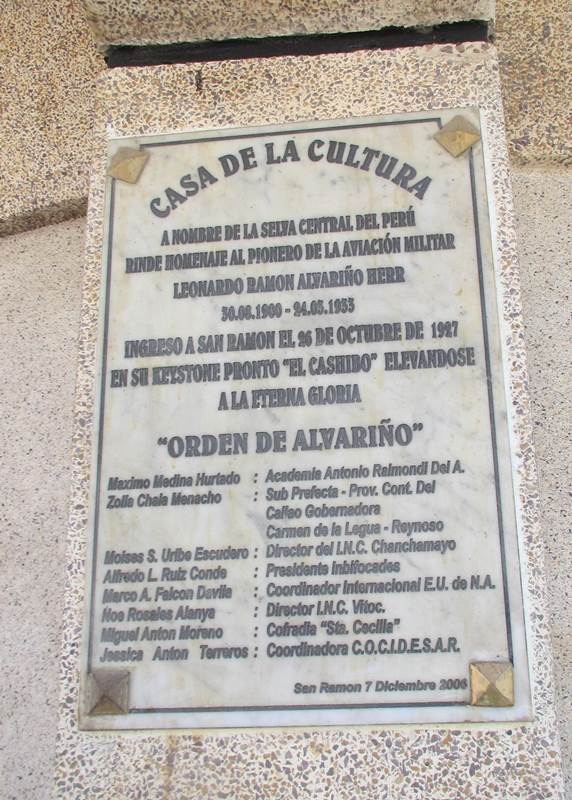

Serving in the Jungle Gateway Known as the 'Ceja de Selva'

By Karen and Duane Sherer Stoltzfus

Peru SST Co-Directors, 2014-2015

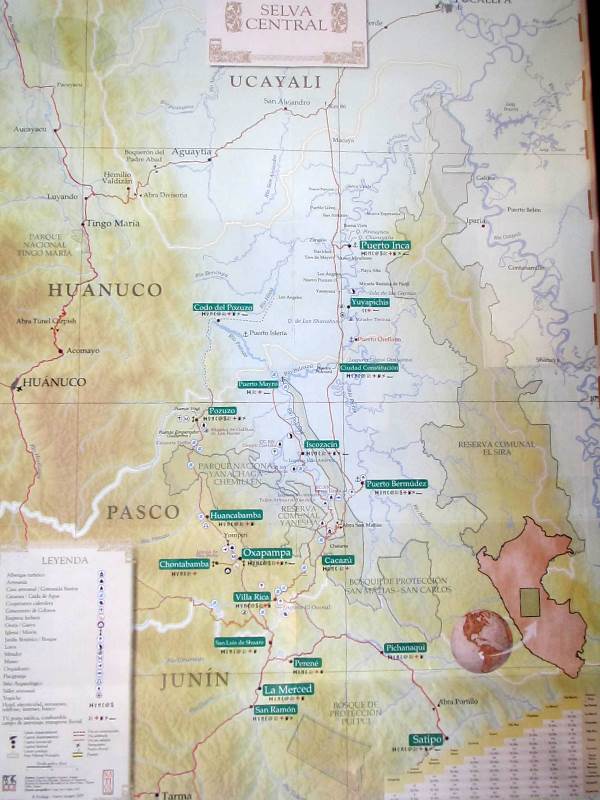

If you are bound for the city of San Ramón, as Jessica was, you have a choice of many different bus lines to get there — but all share the same challenging route.

From the dry, coastal city of Lima, the (La Merced line) bus climbs and winds, reaching the mountain pass of Ticlio, the highest point in the central highway, an ear-popping 4,818 meters, or 15,807 feet. It’s a forsaken place, relentlessly cold, where no one lingers, ready made for an apocalyptic film scene.

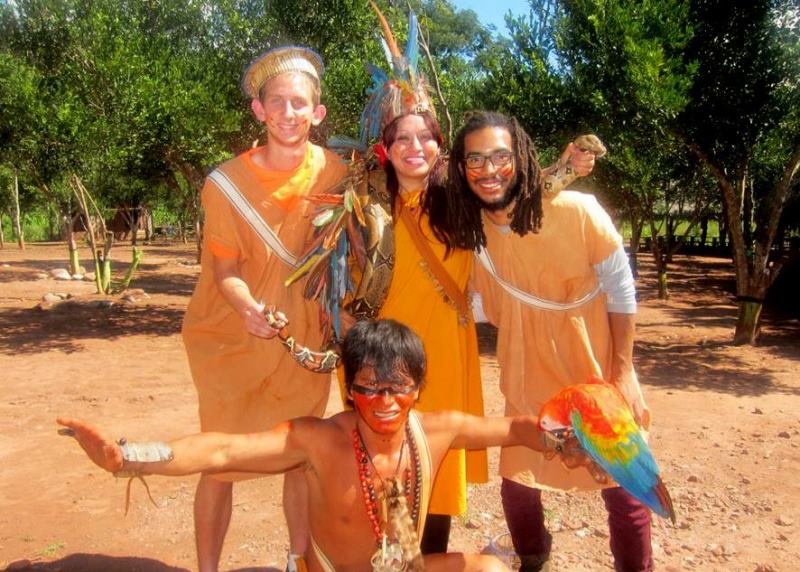

The road quickly descends. Eight hours from Lima, you arrive in San Ramón and La Merced, the lush sister cities of the selva central, situated only six miles apart in the province of Chanchamayo. This is the main entrance to the land of the indigenous communities of the Asháninka, Yanesha, and Amuesha. These ancestral communities have managed to preserve their language and lifestyle over the centuries, though not without many challenges. In the late 20th century, this part of the jungle experienced tremendous political violence. Groups like MRTA and the Shining Path took thousands of the indigenous people as prisoners to strengthen their social based organizations.

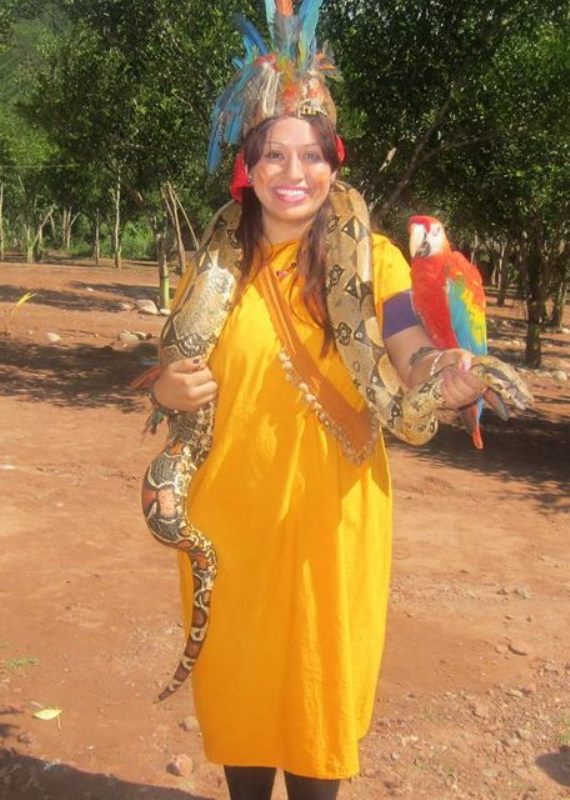

This is also one of the regions that best preserves its biodiversity. Natural protected areas like Pampa Hermosa offers travelers the opportunity to see several species in their natural habitat. Monkeys, parrots, frogs, bears, butterflies, ants, birds, and even pumas, are just some of the species you might see. Tour guides promote trips to nearby waterfalls. In this area you can also buy coffee made from locally grown beans. Markets sell bananas and oranges and fruits that are less well known to North Americans, like quito quito (or naranjilla) and arazá.

But life in the city of San Ramón, where Jessica is living and working, can be difficult for many people, especially for those who have migrated from smaller communities for education or employment.

Jessica, who is in the process of applying to medical school, set out to make the most of her time at the Elera Clinic. On her first day she received training in how to use an electrocardiogram. She observed surgeries. Soon she was traveling with members of the medical team to provide care in remote jungle communities (driving for a couple of hours and then hiking for another hour).

The cases often reflect the difficult life that people lead in the rain forest, from wounds suffered while farming and long delayed treatment to tropical diseases that are unknown in more arid parts of the world. The clinic’s founder, Dr. Gustavo Elera Arevalo, is well known and highly regarded in the area. Patients seek him out because of his expertise and compassionate care (He pioneered a technique, the “Elera Drop,” for temporarily alleviating pain in patients with kidney stones. The technique involves lifting and gently dropping a patient who is resting sideways on a cot).

Through the ever widening network of doctors that she learned to know, Jessica added a part-time service position at the public medical clinic in San Ramón. She works there on Saturday nights and a couple of weekday mornings. Weekends can be busy. She once assisted in stitching a wound on a woman who had been struck by her husband.

Jessica’s host mother, Jeny Mesa Ramo, is a nurse at the Elera Clinic. Jeny and her husband, Carlos, have two children, Lucila and Carlos. Jeny invited us to her home for a midmorning snack of tamales.

In the early afternoon we took a cab to the Kimo camp, situated alongside the Chanchamayo River, just outside the city of La Merced. There are two ways to cross the river here. One is to swim (as at least one Goshen student did in the past). The other is to ride a huaro, a small electric-powered cable car, that can ferry six or so people at a time.

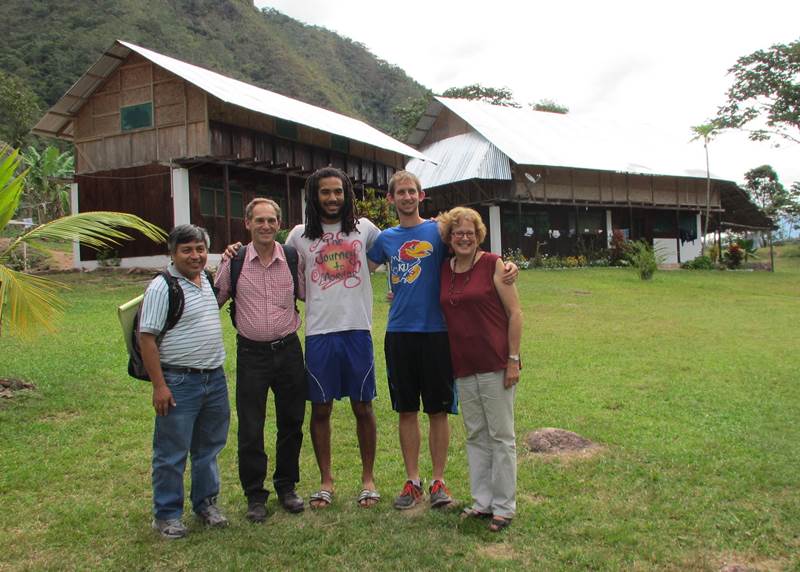

We rode across with Michael and found Josh waiting for us on the other side. They are serving in a camp owned by Unión Bíblica, an evangelical church. The camp, named Kimo (“happiness” in Asháninka, the local indigenous language), is a home for boys who have been abused or neglected by their parents, or whose families are unable to provide for them because of extreme poverty.

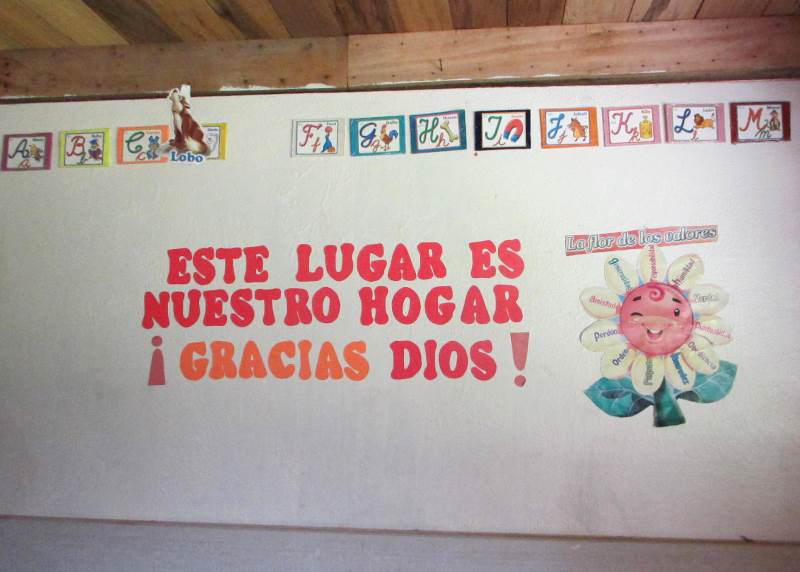

The ministry, called Programa Girasoles (Sunflowers), began in 1987 as work with Lima street children out of a van. It has grown to seven homes for abandoned children throughout Peru. Each home has room for up to 40 children and all are funded by donations.

Kimo is home to 17 boys, ranging in age from 4 to 18. The boys attend public school in La Merced — and receive English lessons from Josh and Michael back at Kimo. A private tutor also visits Kimo each weekday afternoon.

Michael and Josh also do maintenance work at the camp. They built a multi-shelf storage unit for the classroom and have applied fresh coats of paint indoors and outdoors. They learned the process of gathering 10-foot plants to dry and weave onto rooftops.

In the evenings there’s time to play soccer or hang out in the comedor, or dining room. It’s a full day. They are usually in bed by 9 p.m.

We visited with the program directors, Henry Viguria Huaman and Eva Yasauk Krivenchuk, over tea and breads. They told us about how the boys are being raised here as young Christian gentlemen, with a reward each year for having done well. The goal this year is to raise money to visit Machu Picchu.

Josh and Michael are among seven students who are serving in the selva, the “Jungle Crew.” Students in each community have taken turns hosting the others. Jessica, David, Zach, Anna and Claire had a sleepover at Kimo one weekend.

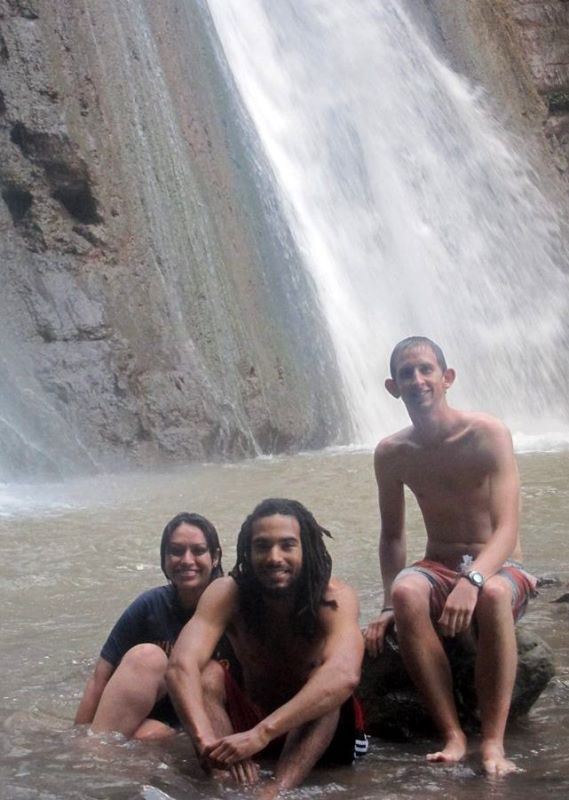

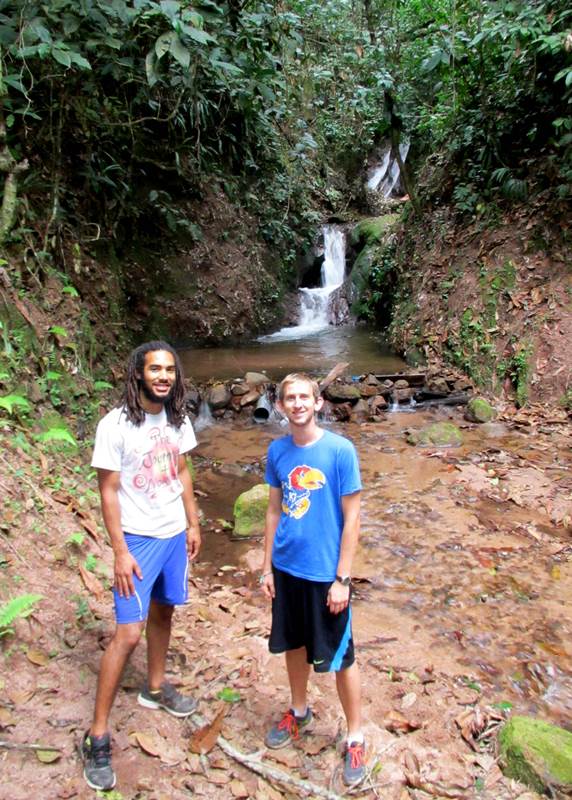

Kimo is a beautiful jungle property of 145 hectares (358 acres). In addition to the home for boys, the property is used as a retreat center and campground for Unión Bíblica and has hiking paths and 14 waterfalls.

Our afternoon at Kimo went quickly. We had just enough time for Michael and Josh to take us on a hike to see one of the waterfalls on the property. Shortly after nightfall, they walked us back to the cable car for our ride across the river. Before flagging a cab, we watched them return to the far shore, tracking their flashlight beam across the water.