Serving in San Miguel Among the Asháninka

By Karen and Duane Sherer Stoltzfus

Peru SST Co-Directors, 2014-2015

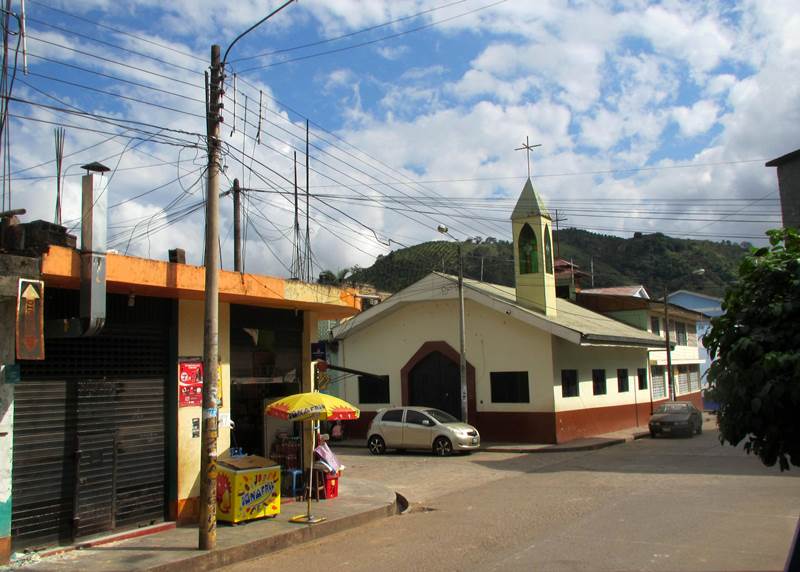

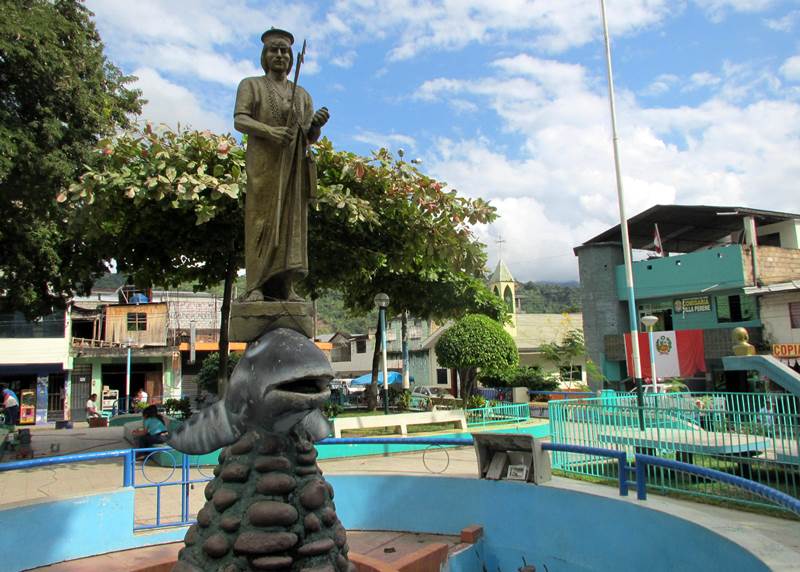

The two young men walking toward us in the plaza in Santa Ana looked like the Zach and David we remembered — only different. Both were tanned and sporting beards. And in another telltale sign that they were living in a jungle community nearby, they had bug bites on their legs and arms.

They had walked an hour or more downhill from their home community, San Miguel, into town. We piled into two motos for the return trip, which, even on motos, took about half an hour on a bumpy dirt road.

David and Zach are living and serving with people for whom Spanish is a second language in a tiny settlement deep in the central jungle of Peru. San Miguel de Marankiari is an indigenous community perched on a hillside far above the Perené River Valley, in the province of Chanchamayo and the state of Junin.

San Miguel is home to several dozen indigenous Asháninka families (about 100 people in all), who live in the jungle at the edge of the Amazon. Tribal history tells of an elder and his three wives, displaced from their ancestral homeland in the valley below, who founded the community some 60 years ago.

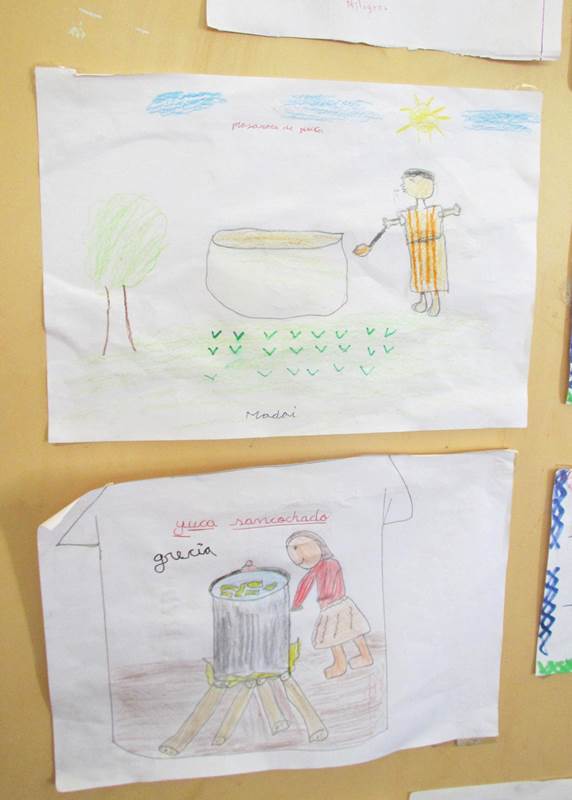

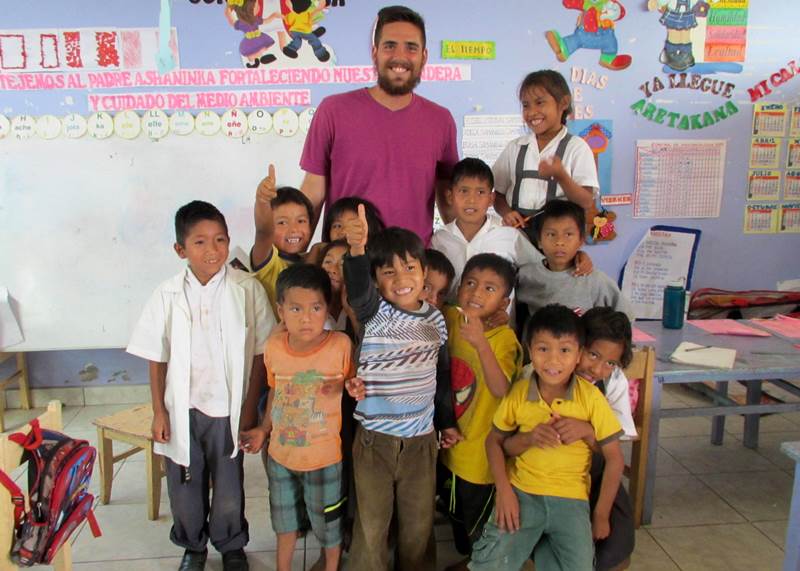

Zach and David spend time teaching English to classes of school children. On the day we visited David devoted time to kitchen vocabulary: plate, cup, pot, fork, spoon. He illustrated each of the items on the whiteboard. Meanwhile, in a classroom next door, children gathered in close around Zach as he used family photos to introduce words for sister, brother, mother, father.

They also participate in the routines of life in the community, including playing soccer barefooted. Traditionally, soccer is reserved for boys and volleyball for girls. On at least one occasion, David and Zach showed that these lines can be crossed, as they joined in a volleyball game.

Both have become students of the Asháninka way of life. They learned to harvest, dry and package coffee beans. They wash their own clothes (and in Zach’s case, hung the clothes to dry on coffee plants). They have joined in the making of pachamanca, in which the earth is used as a sealed oven for cooking yucca, chicken or pork, and corn. They have planted banana trees and helped out in other ways on their families’ small farms.

Fruit appears to always be within reach. From his room, David looks out on a mango tree.

Minutes after we arrived, we were treated to a bowl of tangelo oranges and slices of papaya. Lunch later that day included quito quito juice; chicharrón, or fried, armadillo; and a platter of chicken and yuca, wrapped inside steaming leaves of the bijao plant. We tried to learn a bit of the native language to thank them (“pasonki”) for the delicious (“pushini”) meal.

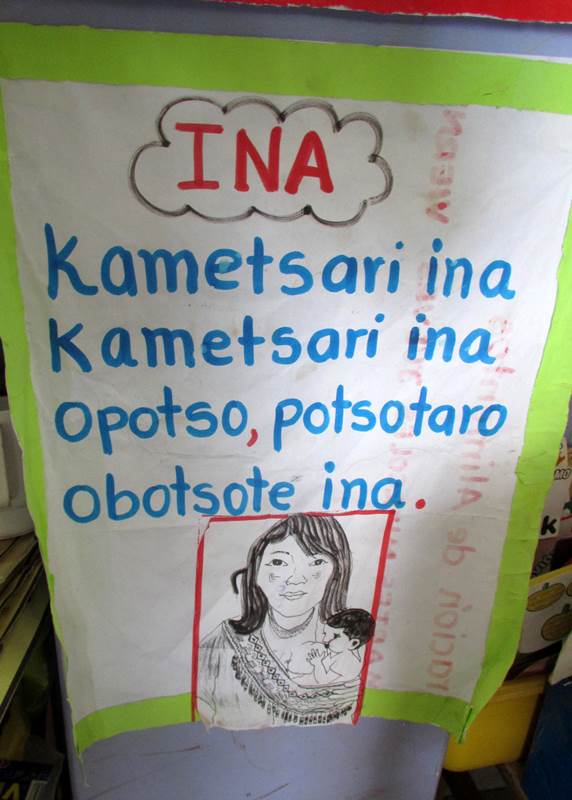

More than 25,000 people still speak the language of the Asháninkas, one of dozens of native nations that originated in the Amazon basin (now parts of Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia and Bolivia).

Many people still live far off the beaten path, but the Asháninka people are quickly becoming westernized due to forces often beyond their control. Their native language, customs, traditional diet and ways of life are disappearing as members move to cities to pursue an education or make a living.

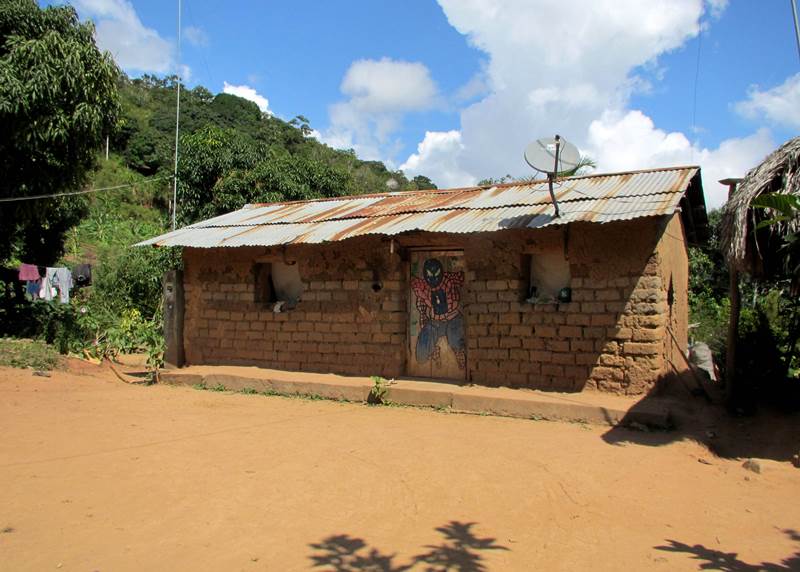

In San Miguel, electricity, water and sewer systems, and even satellite television have arrived in recent years, bringing comforts but also changing life. Community members are trying to preserve the best of their traditional lifestyle. The founders of Ecomundos, a non-profit organization based in San Miguel, are proud of their Asháninka heritage and are helping the community maintain its distinct identity and customs and stay free of destructive outside influences.

Community leaders hope that cultural tourism, in which a limited number of outsiders (no more than 100 per year) pay to visit and stay overnight in San Miguel in order to experience the unique aspects of Asháninka culture, can provide incomes to families who choose to remain in the village. On the day we visited, San Miguel was also hosting a group of French doctors who had come to study traditional medicine.

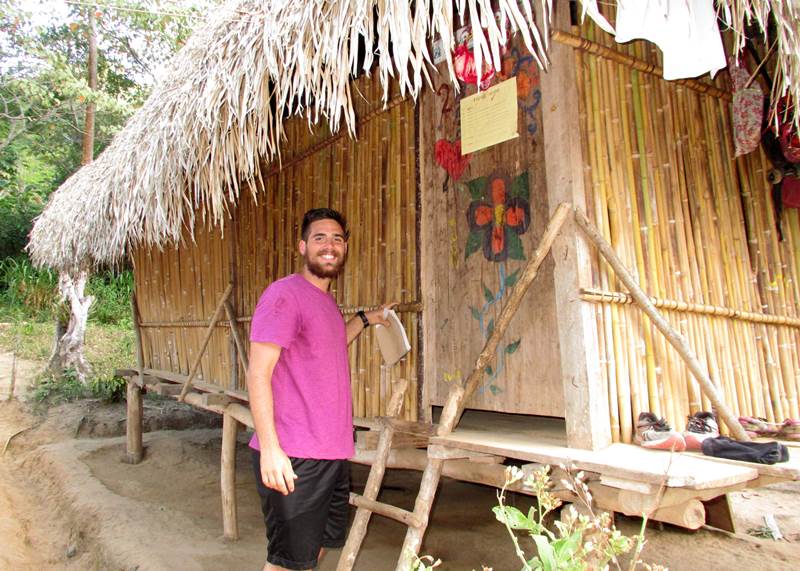

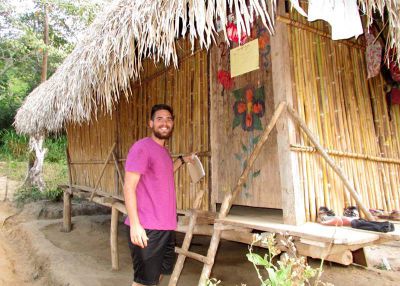

Many of the residents of San Miguel still live in houses built of carrizo (bamboo), dress in their traditional cushmas, cultivate traditional foods such as yuca and plantains during the day and hunt for game at night, sometimes with a bow and arrow.

A friend in the community made bows and arrows for David and Zach. They’re hoping to be able to take them along home using a PVC pipe as safe storage. The cushmas will be easier to pack.

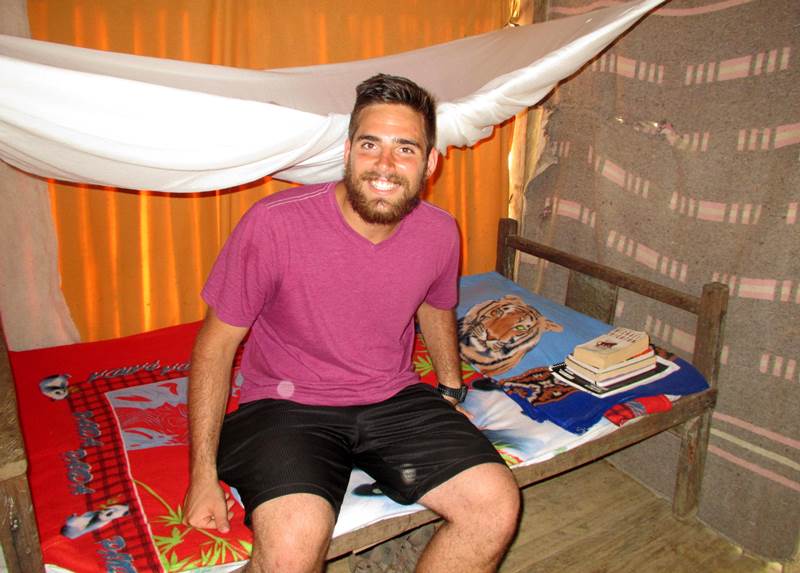

Service in San Miguel means entering into the rhythms of the community. David and Zach wake with the sun and go to bed not long after nightfall, usually around 9. If it’s raining, Zach may fall asleep to the sound of chickens, as they like to gather underneath his bamboo hut to stay dry. If it’s clear, they can look out on a canopy of stars.