Shedding light on the Shining Path war

Just as the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 traumatized many people in the United States, Peru’s war on terror in the 1980s and 1990s continues to traumatize Peruvians. And just as in the United States, the final chapter of the war has yet to be written.

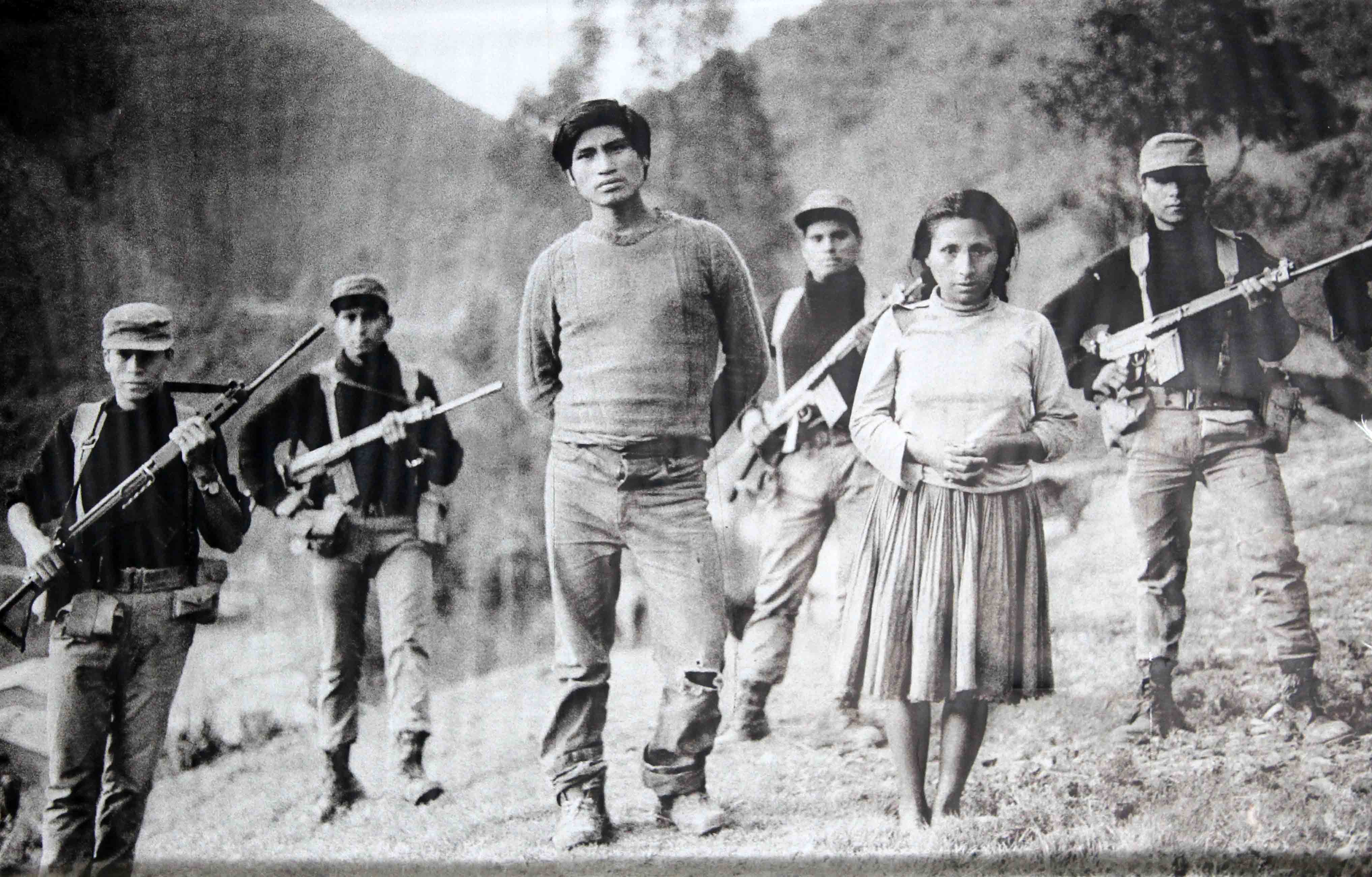

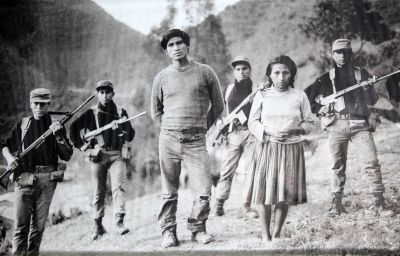

In 1980, members of the Communist Party of Peru, more commonly known as the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), began a guerilla war to overthrow the government, elevate the rural poor and establish a communist state modeled on the philosophy of Mao Zedung (Mao Tse-tung), the founder of the People’s Republic of China. Besides attacking government forces, the Shining Path relentlessly targeted rural communities and civilians, prompting a fierce counter attack by the police and military. Before ending, the homegrown conflict eventually claimed nearly 70,000 lives.

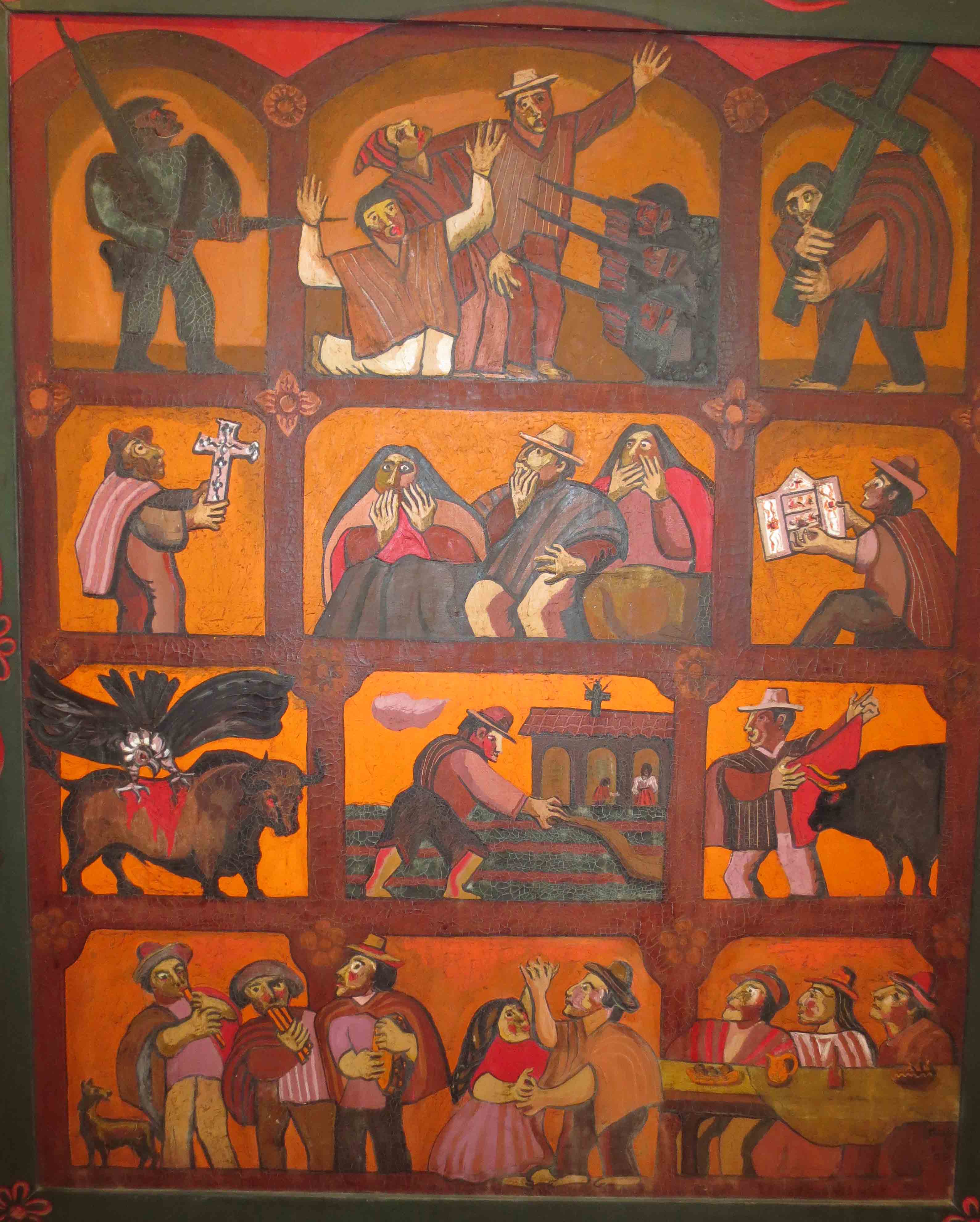

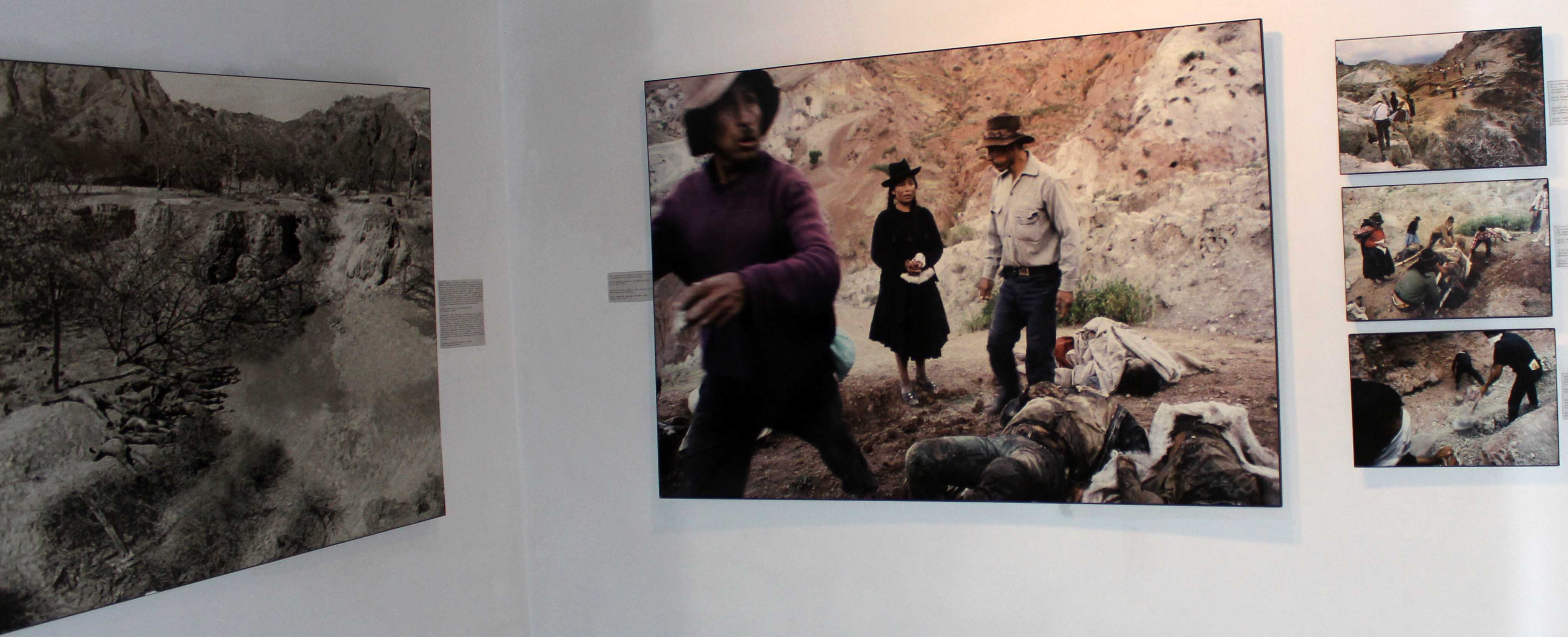

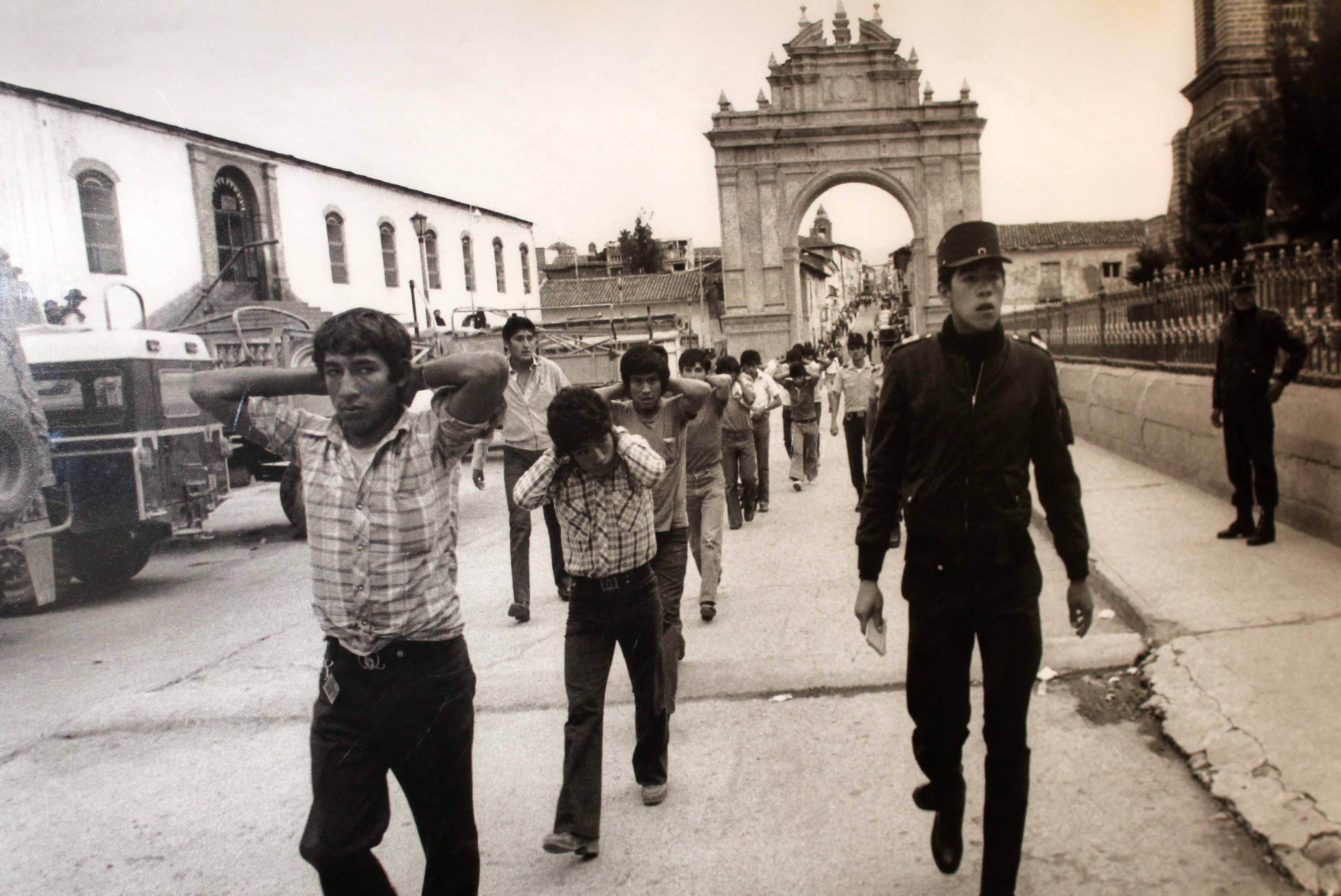

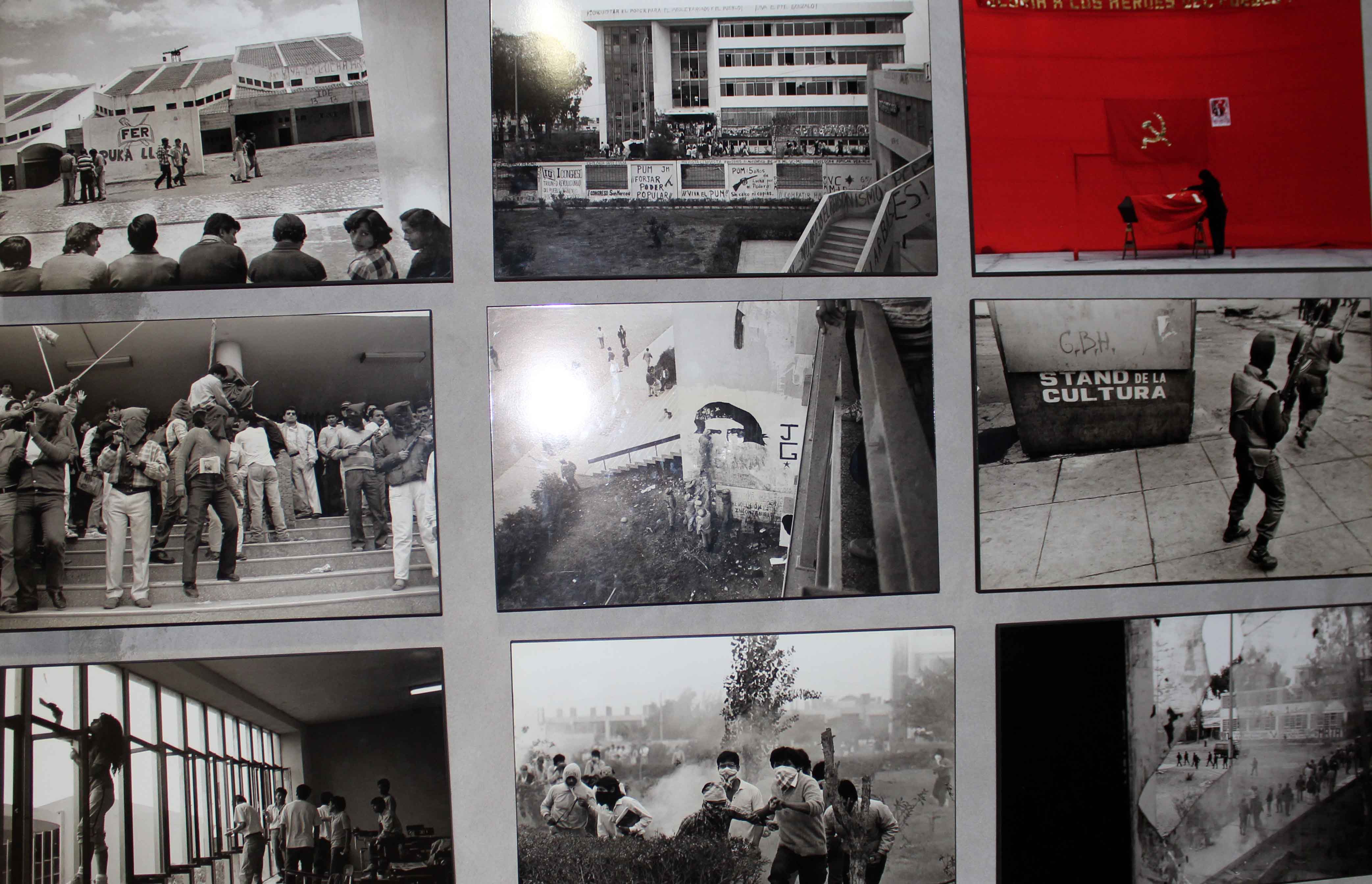

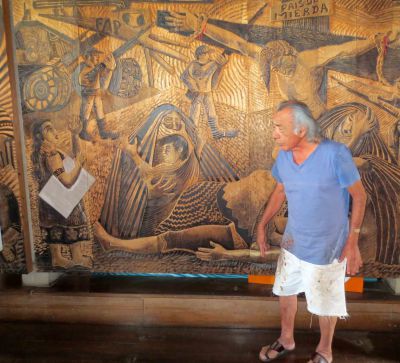

Throughout their time in Peru, Goshen College students have learned about the causes, consequences and continuing impact of the war. Students have engaged with lecturers who witnessed atrocities in what is generally considered the most violent insurgency in late-20th century Latin America. They toured a museum exhibit featuring gripping photographs of the 20-year conflict and viewed related artwork at a galley. They have analyzed articles about the war in the Peru Reader and read Lost City Radio, a novel by Daniel Alarcon, (inspired by events in Peru) about a nation coping with fear, loss and regret in the aftermath of a leftist insurgency. On service in Peru’s provinces, some students heard tragic war stories from host family members and work colleagues. Four students serving in Ayacucho toured a small museum that told the stories of victims in Ayacucho, the state that suffered the most war casualties.

The Rev. Jorge Zamudio Bustamonte, rector of the Catedral del Buen Pastor, shared his vivid personal story about leaving the Catholic Church and eventually finding his way to the Anglican Church. While still a priest, Zamudio was the chaplain to the Peruvian army and learned about atrocities committed by the government, including from soldiers who confessed to torturing and killing suspected guerrillas. They went to Zamudio to seek absolution, penance and peace of mind.

Zamudio also recalled the pain of losing a cousin (an Air Force pilot) who was assassinated in a plaza by Shining Path guerrillas in front of his wife and children. He related his horror of finding the partial remains of a good friend killed in a Shining Path bombing. However, Zamudio also talked about the income inequality that continues to motivate poor Peruvians to seek a government more responsive to their needs. A police officer who guards a rich government minister, for example, complained to Zamudio that with the money the minister spent on her luxury vehicle, he could have purchased a home, a car and a vacation.

Jerry Acosta, a former banker and now an Anglican pastor, told students about surviving the violence and turmoil during the war in his native city of Tingo Maria, in the central jungle. Acosta explained how Shining Path members steadily infiltrated the primary schools, universities, the army, churches and even his extended family. Two of his cousins joined the movement and were killed while defending the Shining Path. He described the evolution of the terrorists’ tactics, how they laundered money sent by international backers and how they teamed up with drug dealers. He also talked about how the government passed extreme anti-terrorism laws and stepped up the war, triggering even more brutality by the guerrillas.

In one village, Acosta said that he and other witnesses were forced to participate in the torture of a community leader, who eventually was shot and killed by terrorists. The fear and anguish of that moment was so great, Acosta recalled, “that I felt as if my soul left my body.” After later refusing to allow his bank to continue to pay bribes to the Shining Path, Acosta said he narrowly escaped an assassination attempt by a teenage boy with a hand grenade; the boy, who was running toward him, tripped, fell on the grenade and blew himself up. Like hundreds of thousands of people living in the provinces, Acosta finally moved his family to Lima in search of safety and the chance for a new life.

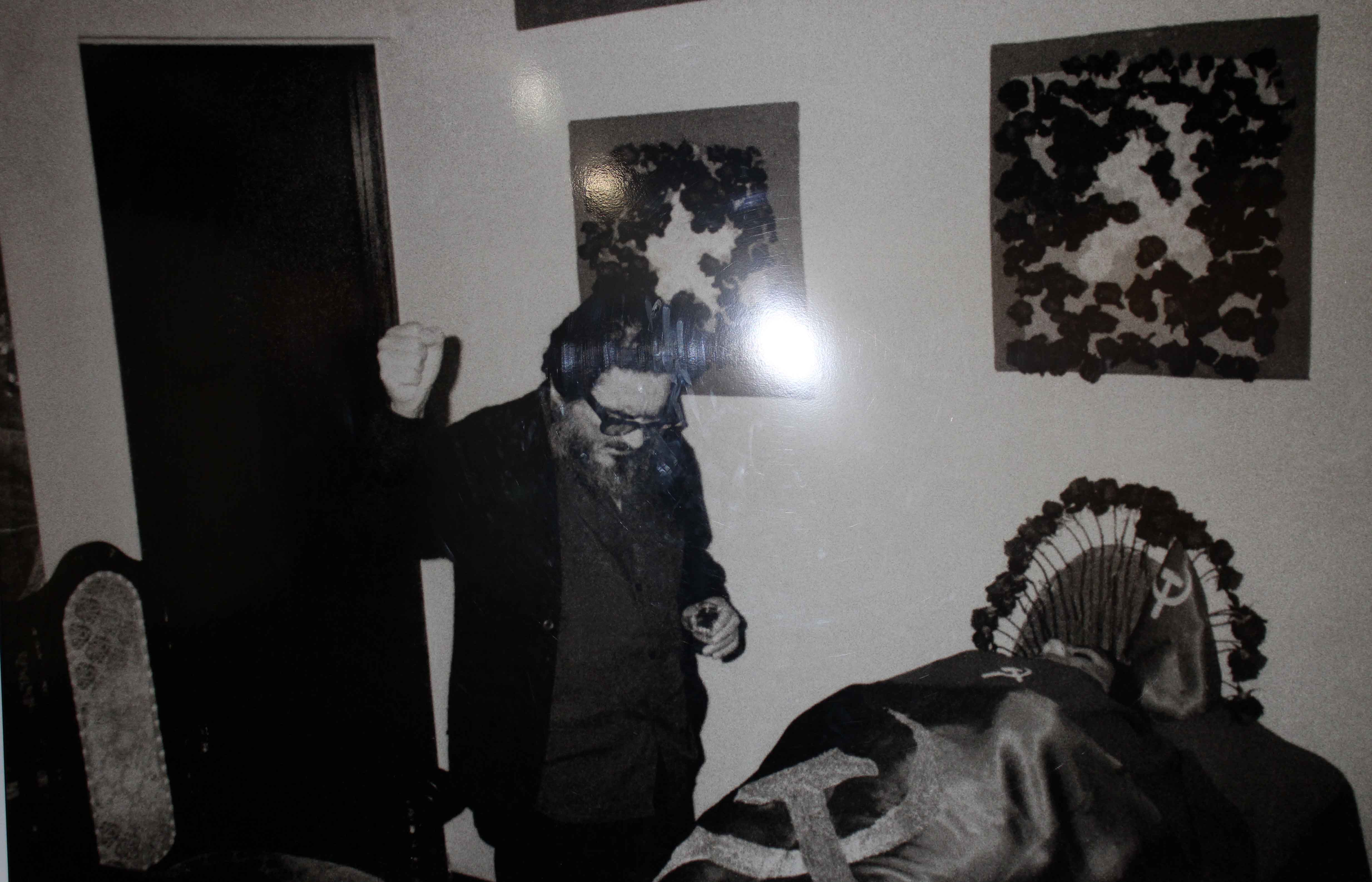

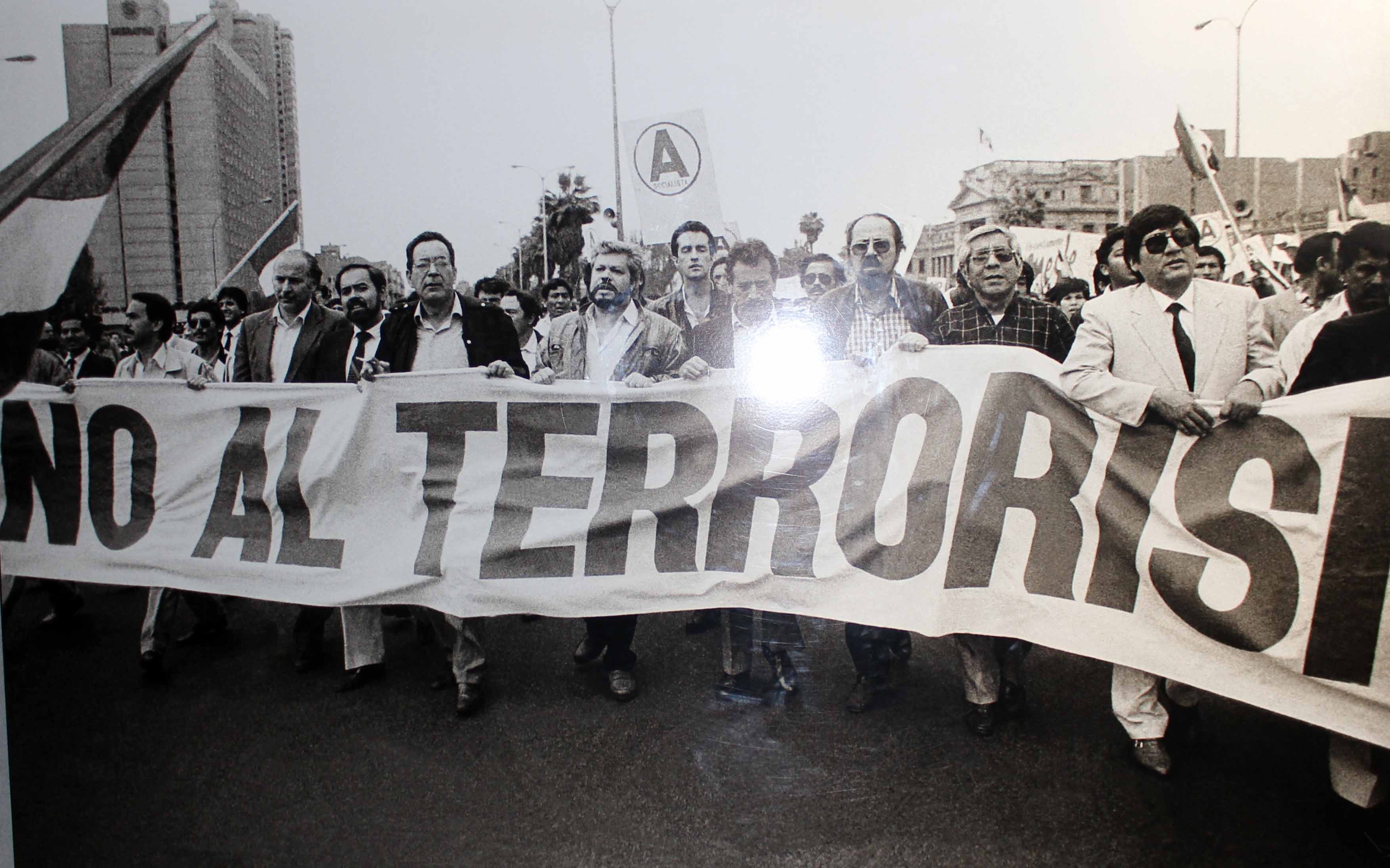

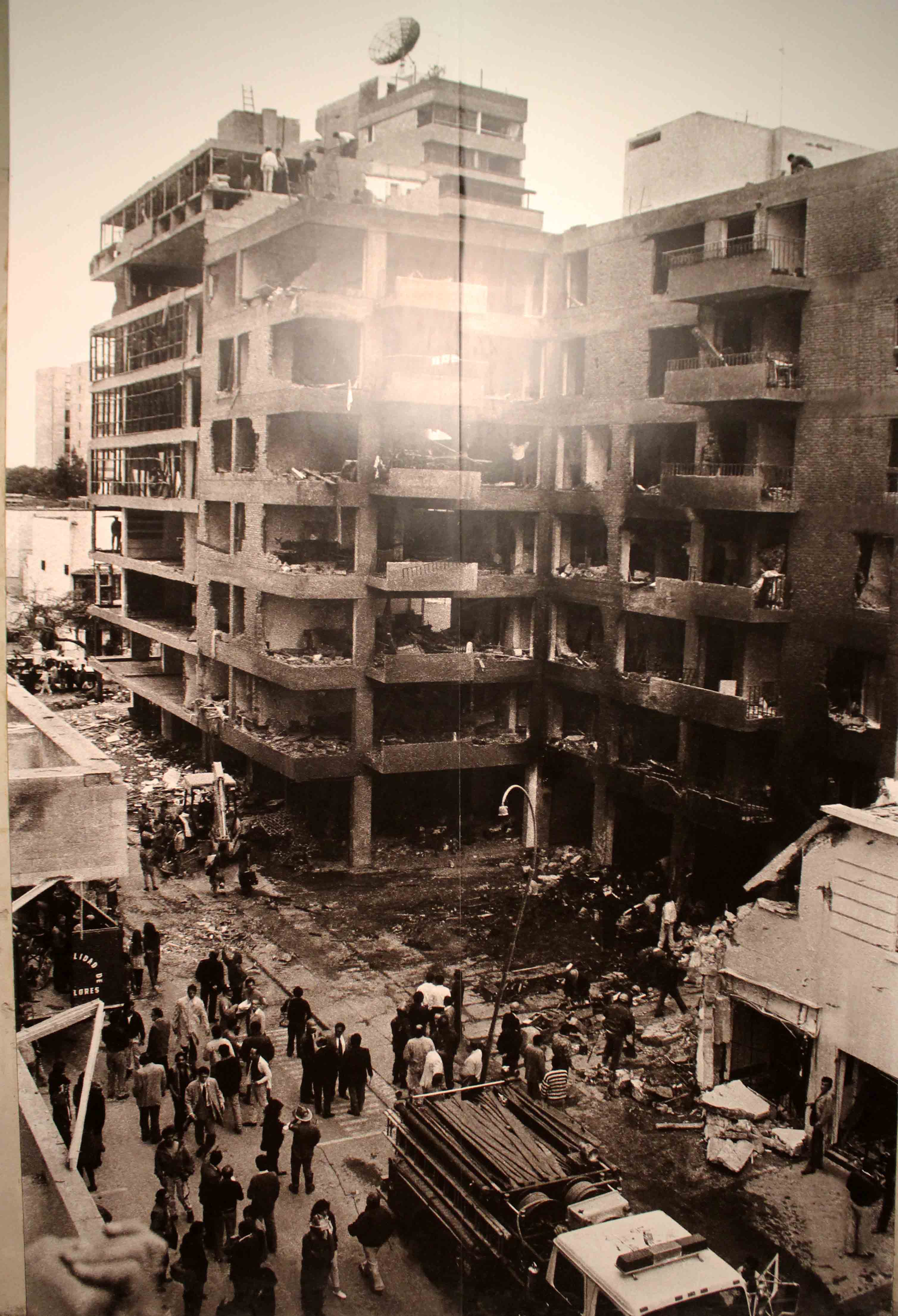

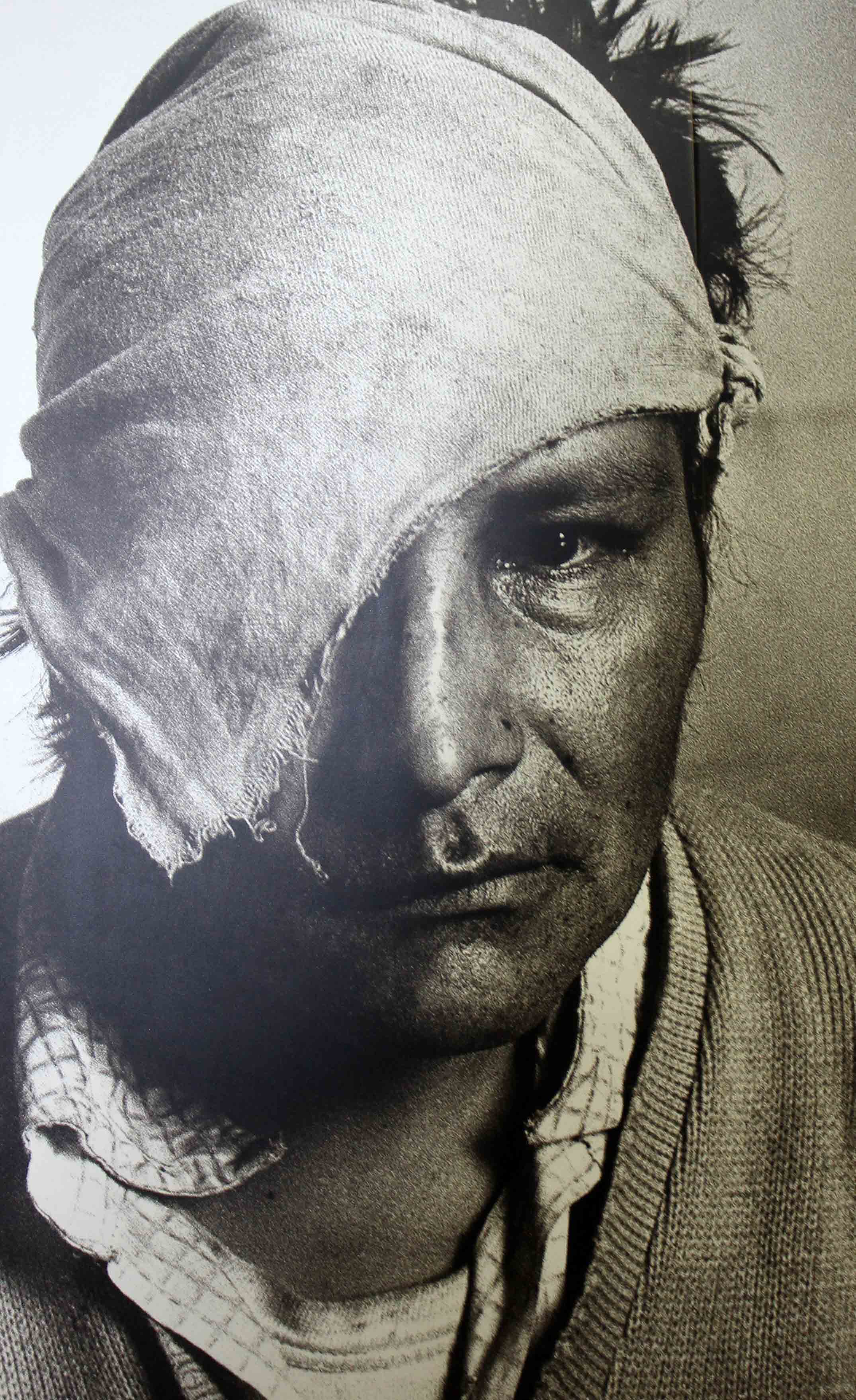

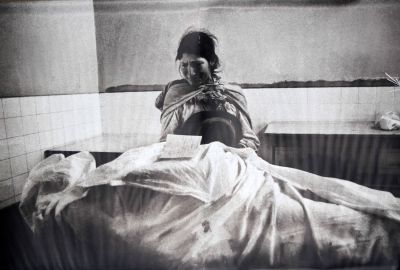

During a tour of the Museo de la Nación, students gained a clear sense of the human cost of the conflict by viewing a 250-photo exhibit named Ypuyanapaq, a Quechua word which means “To Remember.” Opened in 2003, the exhibit has been viewed by more than 200,000 Peruvians, including victims and their perpetrators, and is intended to promote reconciliation. Besides depicting the roots of the violence, the exhibit focuses on the many victims and the futility of war.

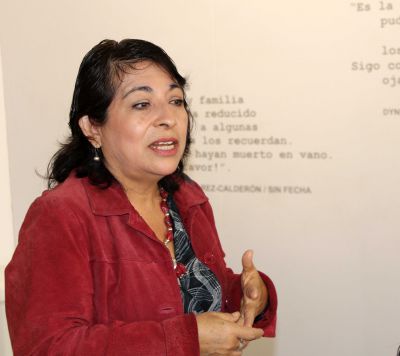

Celia Vasquez, the Peru SST study coordinator, told the students that during the civil war, Lima residents tried their best to live normal lives amid the frequent bombings of cars, buildings and high-voltage power lines, which led to blackouts. At the peak of the war, Lima was considered the world’s second-most dangerous city after Beirut, Lebanon. Vasquez said people were afraid and did not give their opinions about the violence because Shining Path sympathizers and government intelligence officers might be listening. And curfews kept people at home at night.

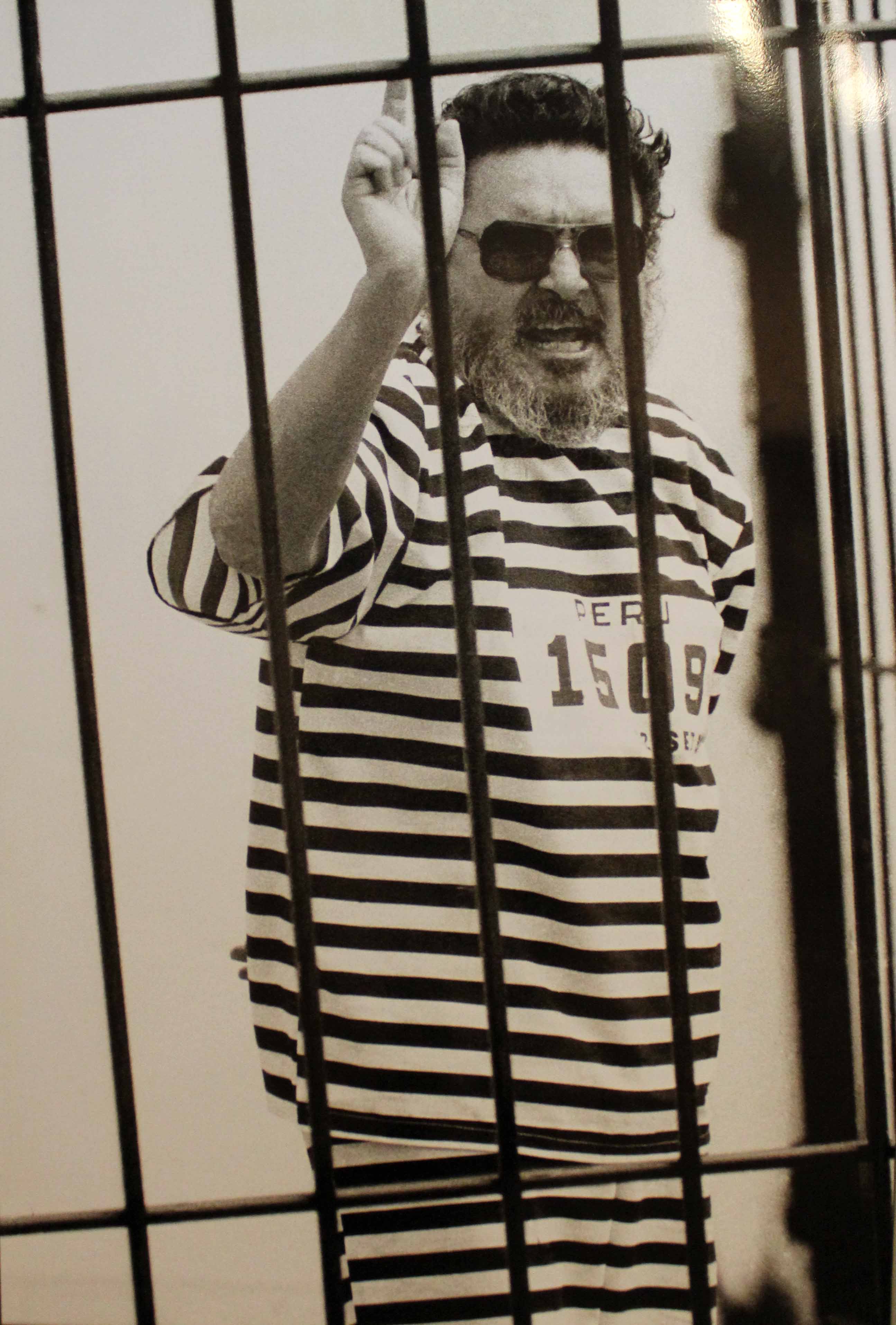

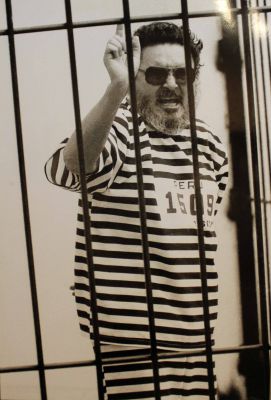

Students learned that Abimael Guzmán, a philosophy professor at the San Cristóbal of Huamanga National University in Ayacucho, founded the Shining Path movement in the late 1960s. The name of the revolutionary movement came from a statement by the Peruvian communist party founder of the 1920s who proclaimed, “El Marxismo-Leninismo abrirá el sendero luminoso hacia la revolución.” (“Marxism-Leninism will open the shining path to revolution.”)

Guzmán gained support among poor people by underscoring the extreme economic, political and social inequalities in Peru and the exploitation of residents of the Andean highlands by upper-class people from Lima and other large cities. Many of his students adopted the communist ideology and support for his movement flourished at some universities. The Shining Path also gained a foothold in many rural communities by forming justice councils that punished petty criminals.

Later, Shining Path members initiated a guerilla war against the government. They disrupted elections, assassinated police and political leaders and also priests. The police and military responded with harsh tactics, sometimes arresting and torturing innocent people and murdering and secretly burying victims. The guerrillas turned to even more violent tactics as well and bombed factories and residences, killed mayors and massacred entire villages whose residents were accused of collaborating with the government.

In September 1992, Peruvian police captured Guzmán in the Surquillo district of Lima. Most other Shining Path leaders were arrested shortly afterward and the rebels suffered a series of military defeats to the government and self-defense organizations of rural residents. The Shining Path broke into factions and additional leaders were captured, officially ending the conflict by 2000.

The government’s Commission of Truth and Reconciliation concluded that 69,280 people Peruvians were killed or disappeared between 1980 and 2000. It has been estimated that as many as 15,000 people remain missing, many believed buried in unmarked graves in the mountains and jungles.

The commission stated that the Shining Path was responsible for about 54 percent of the deaths and disappearances and the police and military were responsible for 28 percent. The rest were victims of paramilitary militia groups and smaller guerrilla groups. Eighty-five percent of the victims were from the poorest regions of the Andes and 75 percent belonged to the indigenous Quechua-speaking population. In addition, more than 200,000 people were traumatized by torture, rape and other war crimes and more than 600,000 people, mostly from the Andean highlands, fled their homes to escape the violence and many migrated to Lima.

Shining Path activity today is limited to a few isolated areas in the highlands and jungle. Some factions either smuggle drugs or provide protection for cocaine growers and processors. Other factions are fighting the government to force a peace process and to free imprisoned Shining Path leaders. While the government seeks to downplay the impact of the war, rebels continue to attack military units. The continual discovery of mass graves and the ongoing arrests and prosecutions of Shining Path leaders also keeps the conflict in the news.

For many survivors of the conflict, some still searching for “disappeared” family members and friends, the war is a painful and constant presence in their lives. And for them, the search for truth, reconciliation and peace remains an elusive dream.