December 19, 2003

Tanzania’s Serengeti is widely-known as being one of the last remaining wildlife spectacles in the world — home to wildebeests, zebra, elephants, lions, giraffes and more. Yet it is an area where archaeologists have discovered remains of some of the earliest known humans.

Goshen College Associate Professor of History Jan Bender Shetler’s recent research has produced two key understandings that reconstruct how the Serengeti has been portrayed and understood since the late 1800s when Europeans arrived and the land was by then empty of people, but ripe as a “hunter’s paradise.”

First, the land was not historically empty of humans, as the Serengeti National Park promotes — there are signs in the park today that say: “People have never lived here.”

“During my dissertation research I collected oral traditions from peoples now living on the western borders of the park who remembered settlement sites and sacred places now within the park,” Bender Shetler said.

And second, the people who lived in the Serengeti are to be credited for the environmental preservation and the park’s pristine beauty today. “I found that these peoples had helped create the landscapes we now see as natural over the past 2,000 years, as they burned the grass, cleared the bush and encouraged certain kinds of vegetation to feed their livestock, attract the wildebeest herds, maintain boundaries with their neighbors and control disease vectors,” she said.

Bender Shetler received a $24,000 fellowship for university teachers from the National Endowment for the Humanities to continue previous doctoral research on the Serengeti people and land, and write a book. Bender Shetler, who received master’s and doctorate degrees from the University of Florida, hopes the book will be published in 2005 and accessible for college students studying African history and environmental history, but also for people working in conservation in the Serengeti region.

“The book seeks to both humanize and complicate popular understandings of the Serengeti as a pristine wilderness by giving agency to those people who helped create it,” said Bender Shetler. “This is a study of environmental history and looks at long-term relationships between people and the environment and how they both changed over time.”

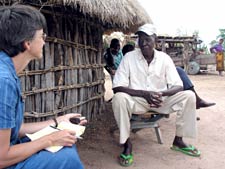

During three months this past summer, Bender Shetler spent time in Tanzania and cities in England, interviewing park conservation workers and persons with ancestral connections to the land, and researching official Colonial documents “to show, over the long term, how [the western Serengeti peoples] have interacted and nurtured their environment — and then how they got dispossessed of this land and labeled as the poachers during the Colonial era,” she said.

While interviewing western Serengeti local elders, Bender Shetler traveled with them into the Game Reserve that surrounds Serengeti National Park as a buffer zone, which they haven’t been in for 30 years. “They nearly cried when they entered the park because it is such sacred ground to them,” she said. “They could identify exact spots where there used to be a settlement prior to abandoning them as a result of Maasai raiding, epidemics and drought in the late 19th century.”The location of these sites has been passed down from one generation to the next since that time. According to Bender Shetler, the elders she spent time with knew about the settlement locations because their fathers and grandfathers had pointed them out during hunting trips when they were younger. Using a global positioning system, she marked important locations with plans to make a map of the area and the settlements.

“I am trying to give these people a voice because they have been silenced and given no say over their ancestral land,” Bender Shetler said. “I want to be able to insert a new historical voice from the communities surrounding the park to the discussions of tourists, policy makers, conservationists, development workers, park managers, academics and students as they think about the future of AfricaÕs humanized wilderness.”

Since returning to the United States in September, Bender Shetler has been writing the rough draft for her book while on leave from teaching. A 1978 Goshen College graduate, Bender Shetler spent a year and a half doing research in the Serengeti region in 1995 and 1996 toward her dissertation, and lived in Tanzania’s Mara region from 1985 to 1991 as a development worker with Mennonite Central Committee and the Tanzania Mennonite Church. Among the courses she teaches at Goshen College are History of Ethnic Conflict, Christianity in Africa and the Diaspora, African History and History of Global Poverty.

In 2003, the book “Telling Our Own Stories: Local Histories from South Mara, Tanzania,” was published which Bender Shetler edited and translated from Swahili and English. “Before publishing my own interpretation of western Serengeti history, I committed myself to publishing histories written by local authors,” she said.